Attention! Here are the headline-writing techniques you need to master on China’s internet!

As the old saying goes, “A good start is half the battle (好的开始是成功的一半 Hǎo de kāishǐ shì chénggōng de yí bàn).” In China’s fiercely competitive social media sphere, where “[internet] traffic is king (流量为王 liúliàng wéi wáng),” having the right headline can be a crucial way of standing out and, in some exceptional cases, turning those views and clicks into a healthy income as an influencer.

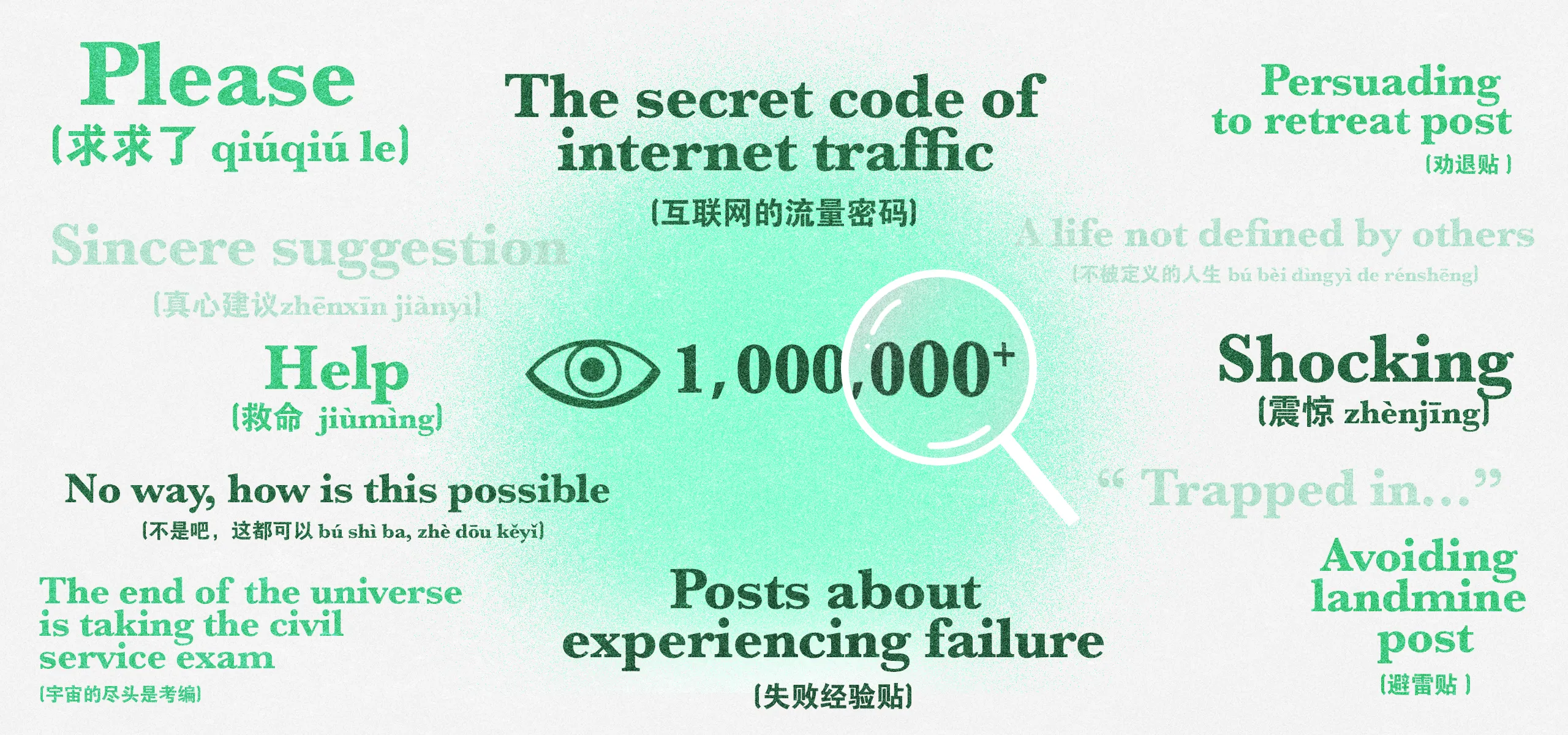

Chinese netizens refer to headlines that leverage current trends, controversy, and emotional manipulation for traffic as having a “sense of the internet (网感 wǎnggǎn)”—in other words, clickbait. These titles tap into “the secret code of internet traffic (互联网的流量密码 hùliánwǎng de liúliàng mìmǎ),” making it impossible for you to ignore them and scroll past (even though you know you should). Clever bloggers and vloggers have developed tried-and-tested formulas that are sure to grab readers’ eyeballs, which should sound familiar to anyone who surfs the net in China today.

Life advice: Be emotional

First, showing empathy and sincerity is essential for encouraging readers to click. Who would say no to posts that seem to understand your sorrow, offer emotional support, or provide honest recommendations? Headlines that begin with phrases like “Please (求求了 qiúqiú le)” or “Sincere suggestion (真心建议 zhēnxīn jiànyì)” are commonly seen on Chinese social media.

Please, you ladies have to try this facial mask!

求求姐妹们一定要尝试这款面膜!

Life advice: Make sure to visit Altay in the fall

人生建议:一定要在秋天去阿勒泰

Everyone wants a shortcut to success, so phrases like “As long as you do… you can… (只要你做…你就会… zhǐyào nǐ zuò… nǐ jiù huì...)” sound very appealing. Exclamations and rhetorical questions also resonate with readers, especially if they relate to a hot social issue, such as “Why on earth is it so difficult for married, childless women to find a job (凭什么女生已婚未育找工作这么难 píng shénme nǚshēng yǐhūn wèiyù zhǎo gōngzuò zhème nán)?”

It may be a truth universally acknowledged that social media was made for showing off, but the right headline can also disguise your boasting into advice that others can follow to replicate your success:

I went from 75 kg to 45 kg in one month, how did I do it?

从150斤到90斤只用了一个月,我是怎么做到的?

A Gen Z saved 300K in just one year of working

00后工作一年存款30万

Avoid! The art of negativity

If sincerity doesn’t do the trick, there’s another option: exaggerating one’s emotions for drama. With expressions like “No way, how is this possible (不是吧,这都可以 bú shì ba, zhè dōu kěyǐ)?” “Help (救命 jiùmìng)!” “Shocking (震惊 zhènjīng)!” or simply “What (什么 shénme)!” writers can pique readers’ natural curiosity and entice them to find more.

Emotions and life lessons don’t need to be positive, either. The internet thrives on negativity, and readers enjoy “posts about experiencing failure (失败经验帖 shībài jīngyàntiě)” as much as (if not more than) successes: either because they hope to avoid making the same mistakes, or just for schadenfreude. Common types include the “persuading to retreat post (劝退帖 quàntuìtiě)” and the “avoiding landmine post 避雷帖 (bìléitiě),” also known as the “avoiding hole post (避坑帖 bìkēngtiě).” These posts compare bad products, travel destinations, businesses, or any other experience to holes you can fall down or hidden bombs that can blow up in your face if you accidentally “step” on them (踩雷 cǎiléi) or 踩坑 (cǎikēng).

Avoid these mines! A list of all the makeup mistakes I’ve made

避雷!细数我走过的美妆弯路

Retreat! A record of harrowing pitfalls at a popular restaurant

劝退!网红餐厅踩坑历险记

Last June, popular blogger Liao Hsin-chung quipped, “There are landmines everywhere in China!” He noted that content with the hashtag 避雷 had 4 billion total views on lifestyle app Xiaohongshu at his time of writing, and almost every city in China had posts warning people to stay away. He called the term “landmine” a “gimmick (噱头 xuétóu)” that almost guarantees strong opinions and debate, thus generating hordes of identical-sounding headlines.

Headlines stuck in the system

It can be hard to tell among all the life tips, landmines, and funny memes, but posts and articles addressing social issues or conflicts still exist on the internet, and they too have mastered certain codes and formulas to grab attention.

In 2020, a long piece of investigative journalism titled “Delivery Drivers Trapped in the System (外卖骑手,困在系统里 Wàimài qíshǒu, kùn zài xìtǒng li)” was published by Portrait magazine to wide acclaim, as it exposed how automation of the gig economy via food delivery apps forced China’s delivery workers to put up with longer hours and dehumanizing conditions. The format, “XX Trapped in...” has since been replicated by a host of other media and adopted by netizens to illustrate social predicaments.

Another popular headline style for contemporary plights and concerns can be found in this 2020 article from Shanghai-based news site The Paper on “small-town test-takers,” students of less privileged backgrounds who dedicate intense time and resources to studying for the college entrance examination as they have no other path to success:

Small-town test-takers: Is it possible to live a life that isn’t defined by others?

小镇做题家,过不被定义的人生有可能吗?

According to headlines, women, college students, and middle-aged people are all struggling to live lives not defined by others.

Another hot topic recently appearing in many headlines is the “Chinese-style family (中式家庭 Zhōngshì jiātíng)” or “East Asian parents (东亚父母 Dōngyà fùmǔ)”:

In Chinese-style families, why are parent-child relationships so twisted?

中式家庭中,为什么亲子关系那么拧巴?

East Asian parents have a hard time telling their kids “sorry”

东亚父母,难以对孩子说出“对不起”

Those who don’t manage to escape societal and family pressures might find themselves the subject of another headline type: “The end of the universe is taking the civil service exam (宇宙的尽头是考编 Yǔzhòu de jìntóu shì kǎo biān),” popularized by a series of articles highlighting young people’s shifting interest from the private sector to stable, respectable civil service jobs amid growing unemployment and economic uncertainty. Netizens adopt the phrase of “the end of the universe is...” to describe bitter compromises they’ve made and their sense of helplessness over their life choices.

Given the sense of “involution (内卷 nèijuǎn)” in all parts of modern Chinese society, it should come as no surprise that clickbait headlines are becoming over-saturated on the internet, and it’s hard to gain fame and fortune on the internet through clicks alone. It’s important to remember that, no matter how dramatic or unusual a title may be, these are just tricks to grab attention: The quality of the article is what matters.

The Art of Chinese Clickbait is a story from our issue, “New Game.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.