A simple Dongbei dish symbolizes the rise, fall, and reinvention of a once-flourishing industrial heartland

For a city built on heavy industry, Shenyang’s most famous dish is surprisingly frugal. Jijia, little more than fried or roasted leftover bones and scraps from a chicken carcass, is the pride of the city, despite competition from other traditional dishes like barbecued meat, deep-fried pork, and various stews.

In 2021, when China was under strict Covid-19 controls, jijia even gained national attention. The humble cuisine featured prominently in the travel records of an infected man in Shenyang, the provincial capital of Liaoning—he had visited three different jijia (鸡架, literally “chicken frame”) restaurants in just three days.

Jijia and the city blew up on social media. On Weibo, a Chinese Twitter-like platform, a flood of over 80,000 comments under the hashtag “Shenyang jijia” discussed why this brittle, handheld snack of mostly bones was so attractive. Taiwan writer Liao Hsin-chung asked the question on behalf of many netizens: “How delicious, exactly, is jijia? Does every Covid patient in Shenyang have jijia on their travel record?”

Famous Shenyang actor Lin Gengxin soon contributed a widely praised answer: The soul of jijia isn’t its meat but lies in the process of ‘suole’—a local dialect term meaning to suck on food to absorb all the flavor.

But jijia, like any good culinary cultural icon, is about much more than its taste or even the way it is eaten. The snack is not an ancient classic—it only became popular in the 1990s, when Dongbei (a collective name for China’s northeastern Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang provinces) experienced economic and social dislocation as state-owned enterprises closed, forcing millions of blue-collar workers into unemployment.

Once the technological and industrial hub of New China after 1949, Dongbei was forced to reinvent itself. As unemployment rose, wages fell, and households pinched their pennies, leftover chicken bones became a common cheap eat.

Somehow its popularity stuck, despite a return to more stable times (though Dongbei still lags behind the most developed eastern coastal provinces in China by most economic measures).

Despite the scholar Yang Xiu (杨修) of the Three Kingdoms period (220 – 280) commenting ambivalently that jijia was “tasteless if eaten, but a pity to throw away,” there are now over 1,000 registered catering companies in Shenyang with “jijia” in their name, according to Qichacha, a business inquiry platform. According to Taste Humanity at Night, a documentary aired in 2019, Shenyang residents consume nearly half of all China’s jijia.

In the 1980s, “People began to eat jijia because it’s cheaper than chicken meat” says Wang Jue, a 35-year-old Shenyang local who works for a technology company. “When people used to be rich, they didn’t eat it.”

From the 1950s to the 1980s, Shenyang was the most developed city in Dongbei and the site of almost three-quarters of the country’s heavy industry. Those glory days saw most working in state-owned factories doing “iron rice bowl” jobs that promised employment for life. During decades when food could be scarce elsewhere in the country, Shenyang cuisine was often described with a common Chinese saying: “Alcohol in big bowls, meat in big pieces.”

Yet according to a report by the state-media outlet Lifetimes, 71 percent of jijia is bones, 6 percent is skin, and less than 22 percent is meat. On average, one jijia—that is, the carcass of one chicken—comprises less than 100 grams of meat.

Eventually, unemployment and lost wages made big portions of meat too expensive for many. From 1990 to 2012, the number of employees in state-owned and collective enterprises in Shenyang decreased from 2.2 million to 720,000.

In the 2022 documentary Tiexi District, which examined the impact of the restructuring in one of the hardest-hit areas of Shenyang, industrial workers claimed they were given a compensation fee of 226 yuan per month for two years after being laid off (or 下岗). In most instances that was far below what they had earned in the factories, and over 250 yuan lower than the average disposable income of urban residents in China in 1999. Chicken carcasses, which sold for as little as 2 or 3 yuan during the 1990s, were a cheap alternative.

In his 2022 novel The City of Jijia, Liaoning writer Lao Teng reflected on those years of mass lay-offs: “Life became uncertain and depressing. But people must move on. People need to have dinner together, and drink beer. Thus, jijia became popular in Tiexi district, where there were the most laid-off workers. On a summer evening, people would set up a small table and a grill by the side of the street, buy a plate of jijia, and roast them while drinking beer. The whole night wouldn’t cost them more than 10 yuan.”

It was also accessible; readily available at street stalls and eaten with hands only. “If you want to eat barbecue, you need to go to a restaurant. But if you want to eat jijia, you can just buy some casually from a market,” says Wang, who remembers regularly buying three chicken carcasses for 10 yuan on the way home from school as a child.

Nowadays, entire restaurants are devoted to jijia, preparing the dish in a variety of styles. One retired worker opened Old Four Seasons, now a chain of restaurants, in Shenyang in 1988. The restaurant is one of the oldest jijia restaurants in the city, and its signature dish is boiled jijia served with coriander stems and pickled mustard. Customers then add chili oil and vinegar to suit their taste. “I personally like fried jijia better. But you can find that in other cities. The boiled ones you can only taste in Shenyang,” says Wang.

A typical Shenyang meal for one at Old Four Seasons is one jijia, one bowl of noodles, and one beer. The idea is that noodles fill the stomach, jijia satisfies the craving for meat, and alcohol drowns one’s sorrows (perhaps at being laid off from the factories). “The fact that there isn’t much meat makes jijia the best partner for beer,” says Wang. “You will never get too full by eating jijia.”

At Zhang Baoxu’s restaurant, Ma’s Family Jijia, an establishment he has run with his sister since 1994, there are four main varieties on offer: charcoal grilled, baked, smoked, and jijia served cold in a salad. They began selling jijia because the ingredients were cheaper than other dishes. “We sold a jijia for 2.5 yuan at first,” Zhang says. Now it’s 9 yuan a piece, but the restaurant still sells over 1,000 portions a day.

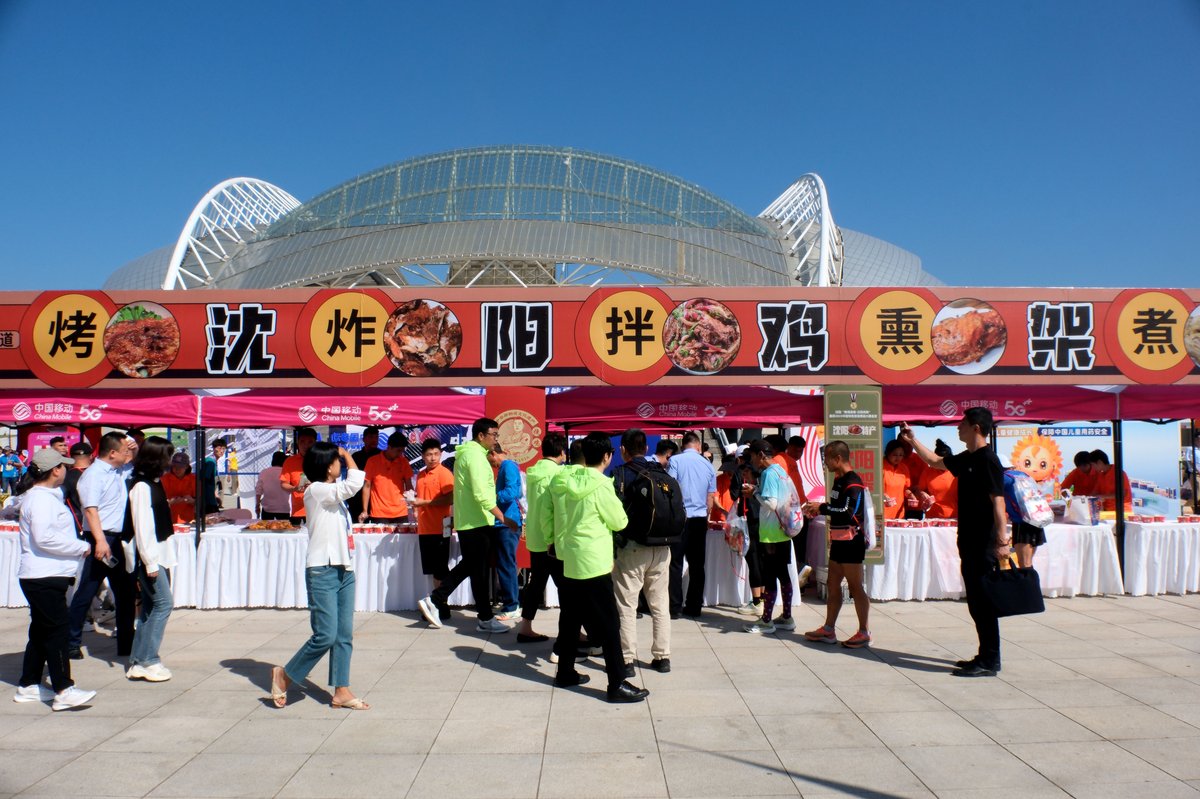

“In recent years, jijia seems to have become more popular. Every day we get customers from other regions coming to have a taste, and sometimes take away some for their friends,” says Zhang. In June 2023, at the Xihongshi night market in Tiexi district, a “jijia museum” area featured dozens of stalls serving varieties of the once working-class snack to tourists and children on vacation from school: roasted, smoked, deep fried, braised in soy sauce…

Though Wang is pleased with the newfound fame of his local dish, he feels it may be misunderstood. To him and other locals, jijia should be seen as less of a symbol of industrial decline than a beloved representation of the city’s industrial heritage.

“Don’t associate jijia with poverty. It’s about industrialization in the first place,” one netizen wrote on the online Q&A platform Zhihu in June this year, in answer to the question “Why do Shenyang people love eating jijia so much.” In fact, part of the reason for jijia’s emergence may not be linked to economic stagnation at all.

When China began large-scale importation of white Plymouth rock chicken—a fast-growing breed of chicken that is cheap to farm—from abroad in the early 1980s, Shenyang was home to the country’s largest state-owned chicken farm. At that time, most of the chickens raised there were for export, but to meet inspection and quarantine requirements for external markets, the chickens were cut apart and packaged in Shenyang before being shipped. That left many leftover bones as by-products, which soon appeared in local markets for cheap.

The opening of the economy in the 1980s and 90s may, therefore, have combined with the closure of state-owned factories to bring about Shenyang’s favorite dish.

Wang also believes regional prejudice fuels the idea that Shenyang residents eat jijia because local living conditions haven’t moved on since the 1990s. “Many people think we eat jijia because we are too poor to afford meat, but they don’t think Wuhan people eat duck necks for the same reason. To some degree, it’s a misunderstanding of Dongbei,” he says. “Is it possible that we eat jijia just because it’s delicious?”

Bones of Industry: Discover Shenyang’s Favorite Street Snack is a story from our issue, “Online Odyssey.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.