Disenfranchised by an increasingly fast-paced society, some younger Chinese are turning to the past to center themselves and regain a sense of comfort

“You have traveled back to the year 2008, and wake to the sound of Tom and Jerry playing on the kids’ channel. Your mom has prepared a plate of chilled watermelon, which you snack on until you and your friends can play Pokémon Go in the afternoon.” Wistful stories like this, capturing the trouble-free living of many Chinese children around the turn of the millennium, have recently gained immense popularity on China’s social media platforms. But rather than Millennials, already weathered by some of life’s storms, leading the creation and consumption of such content, it’s China’s Gen Z, many of who have only just entered the workforce. In an era defined by relentless progress and societal transformation, it is they who are taking a surprising detour—looking back.

While rapid urbanization, technological advancements, and shifting cultural landscapes continue to shape their daily lives, many of China’s 20-somethings are turning to the simplicity of their childhoods for comfort and a sense of identity. And it appears that the trend, affectionately dubbed “Chinese nostalgia-core (中式梦核),” is not just a fleeting moment of collective recall, but rather a reflection of deeper societal shifts.

Childhood memories in the spotlight

“My only regret is that childhood was too brief. Why can’t we just stay in that moment forever?” – Xiaohongshu user Scaleswim

“I’d give anything to go back.” – Xiaohongshu user Fan Debiao

The early 2000s hold a unique charm for China’s Gen Z. It was a time of box televisions, pop idols, point-and-shoot cameras, and cartoons, which together provided the backdrop to their formative years. These memories, preserved in fragments, offer a sharp contrast to the hyper-digitalized world they inhabit today.

“I remember that when I was little, we had a mini TV that could play DVDs in our living room,” 19-year-old Jiang Yusheng, a recent high school graduate from Hebei province, tells TWOC. “It was about the size of two milk crates, and it looked square and simple—nothing like the smart TVs we have today.” Jiang became captivated by images of the past after coming across photos labeled with the hashtag “Millennium Homes” on Douyin, China’s version of TikTok. The collection triggered a barrage of fond recollections for Jiang. “After school I’d flop onto my bed, turn on the TV, and carefully pick out a favorite DVD to watch. It’s such a warm memory that it’s stayed vivid in my mind.”

Read more about youth culture in China:

- China’s Gen Alpha Kids: Gambling Cards, Chasing Happiness

- Why China’s Gen Z Migrant Workers Are Leaving the Assembly Line

- How Gen Z is Changing Work Culture...by Speaking Up

These images and the totems of modern living they revolve around weave the collective tapestry that makes up Chinese nostalgia-core. In it exists a handful of typical, recurring architectural and interior touchpoints—blue reflective window foil, wooden furniture, landline phones protected by dust cloths—instantly transporting the audience back to the early 2000s. Paired with a pixelated aesthetic, they invoke a sense of remembering that is both indistinct and real. “Faded residential buildings, concrete pavilions, and one yuan-goods stores covered in colorful, bold characters—seeing these feels like a revival of my childhood memories,” Jiang said.

Thanks to technology, these images are no longer restricted to the realm of old photographs. On the contrary, most are fake, and increasingly produced with the help of AI. “I will first search the internet for suitable old photographs, then use AI to give these materials a surreal, nostalgia-core style,” 25-year-old Chen Xinyi, a student of Art Therapy and Digital Media Art at Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts, told TWOC. “Even though the pictures are fake, the emotion is real,” she added. “Nowadays we have advanced technology that can make high-quality images. However, these blurry photos hit home in a special way—they bring back memories of the early days of the internet and electronic devices.”

Besides photos, sounds can be equally resonant. The audio of a Windows XP computer booting up, for example, has 41,000 likes on lifestyle app Xiaohongshu. “This sound takes me back to my summer holiday in elementary school,” one commenter wrote. “People enjoyed the online world at that time,” another rued.

There are also various songs and soundtracks specific to the Chinese nostalgia-core style. “These sounds make me feel at ease, like I’m back in my childhood,” Jiang recalled. “For example, (Kenny G’s) ‘Going Home’ or ‘A Mother’s Lullaby,’ which were repeatedly played over our schools’ tannoy, as well as the theme song of Chinese cartoons like Journey to the West and Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf.”

Social media platforms like Xiaohongshu and microblogging site Sina Weibo have helped amplify this nostalgia. In viral posts, people share relics from their childhood, from collectible toys to video game graphics, sparking a collective yearning for the past. The topic “Return to the Millennium” has garnered over 17 million views and 310,000 comments on Xiaohongshu, while “Chinese nostalgia-core” has topped 190 million views. Meanwhile, memes that juxtapose “modern struggles” with “early 2000s joys” bring to mind bittersweet feelings and resonate deeply with those yearning for simpler times.

Looking back to rebel against the present

The reasons for Chinese Gen Z’s deep sense of nostalgia are complex and multifaceted. In general, childhood is a time often remembered as consoling and carefree, so when people find themselves in uncertain times, it’s only natural that they seek a familiar and reliable place to return to. Framed this way, nostalgia-core can be seen as the inverse of how the “dreamcore” aesthetic—often involving existential questions overlayed on dreamy, pre-Photoshop graphics—captured the uneasiness that some Americans felt during the pandemic. The social disorder at the time, whose effects continue to ripple to this day, has significantly intensified the hardships and uncertainties of many of our lives, fueling a growing desire to escape reality. Against this backdrop, dreamcore, which was also primarily embraced by Gen Z, albeit in America, gained popularity on major social media platforms like TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram.

Meanwhile, nostalgia-core has some unique attributes specific to China’s newly crowned adults. Compared to their parents, who grew up in a period marked by material scarcity, Chinese Gen Z was treated to an altogether more vibrant and exhilarating world. Through rapid urbanization, commercial housing and department stores sprang up across the country. As a result, on weekends, children could visit large amusement parks and ride merry-go-rounds or life-sized, land-bound pirate ships, which began appearing inexplicably in China’s second-tier cities. International fast-food chains like KFC and McDonald’s arrived in the late 1980s and early 1990s, followed by video games and Disney movies.

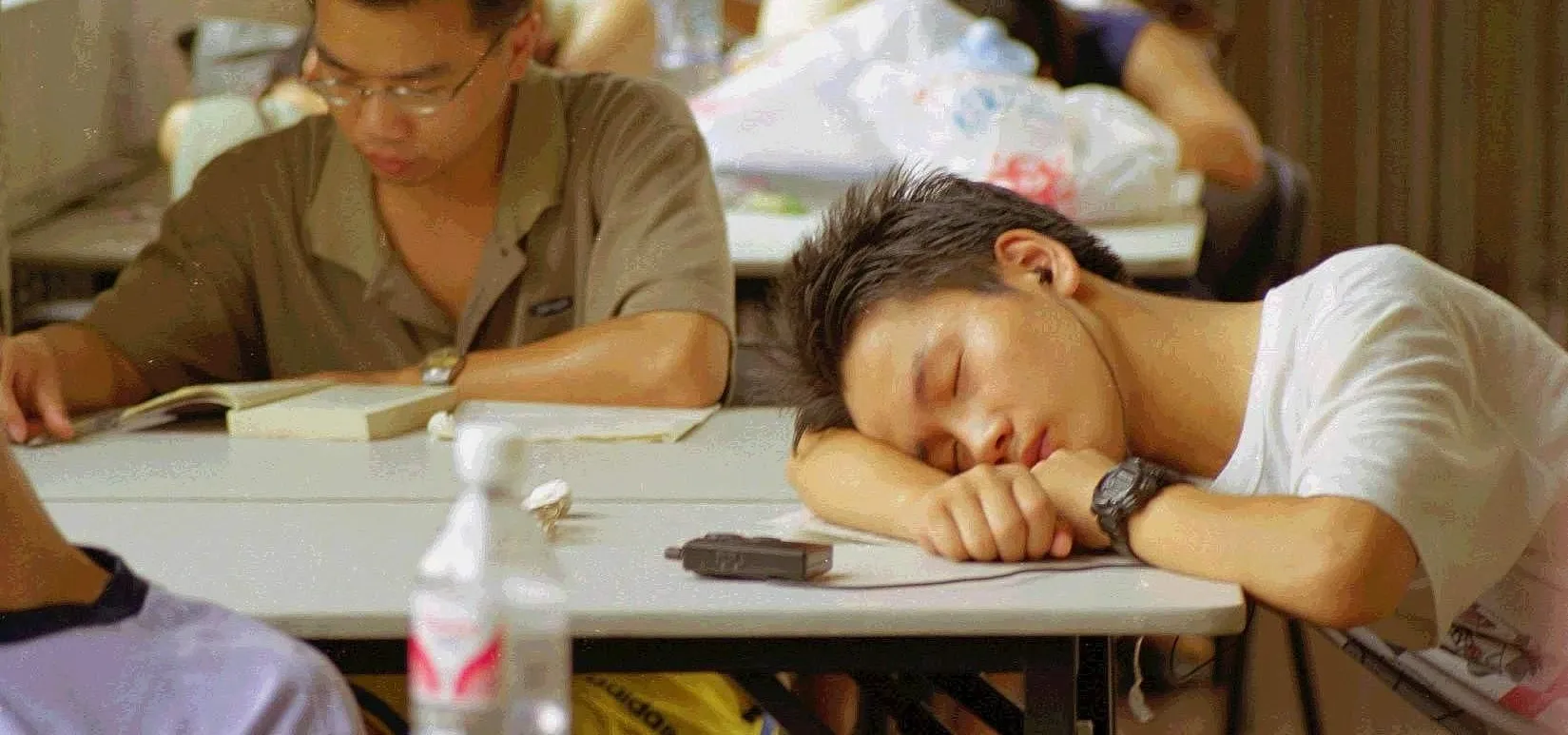

Gen Z also witnessed a golden era in China’s economic and social development, with the country hosting its first Olympic Games in 2008, and the World Expo in 2010. The booming international and domestic markets filled them with hope for the future. But as they grew up, they realized that the real world wasn’t on track to provide the fairy-tale ending they once believed.

A clear example of this newfound cynicism can be seen in the gaming industry. “The 2000s was an era full of dreams. Back then, game development teams were driven by ideals and ambition, unlike now, where the focus seems to be solely on making a quick buck,” Zhu Luo, a 25-year-old collector of millennium-era video games, told TWOC.

Zhu became a fan of these games after being laid off in 2022, five years after graduating from university. He had up to that point been a photographer for a real estate company, but it went bankrupt after China’s real estate industry hit a rough patch. “I think games can also be a way to relieve stress and relax. In a way, they’re a form of compensation for childhood—since I had very few opportunities to play games when I was young,” Zhu added.

Brands have been quick to incorporate these trends into their marketing strategies. In 2022, KFC launched a range of Happy Meal toys co-branded with Gen Z-era IPs like Pokémon and Doraemon. They immediately exploded on social media. At one point, Pokémon Psyduck toys—originally included in a 69-yuan set meal—were reselling for up to 500 yuan, while handheld Tetris consoles shaped like chicken nuggets were going for over 100 yuan on the secondhand market.

Then, in September 2023, Xiaohongshu held a vintage digital device event in Chengdu, following Apple’s autumn product launch the previous week. While the latter adhered to its sleek, future-forward approach, Xiaohongshu opted for a more nostalgic experience, replacing keynote speeches and LED screens with a bustling lane where people showcased their old tech and shared memories through pixelated photos.

What gets left behind in a fast-moving society?

The 21st century has been an era of rapid technological advancement, marked by the growth of the internet, the widespread adoption of smartphones, and more recently, the emergence of AI. Everything is evolving at an unprecedented pace. However, in such a fast-moving society, it can feel as if it is us, the people, who is being left behind.

In a 2024 study on the emergence of Chinese-style dreamcore, scholars Huang Shunming and Liu Xinting from Sichuan University’s College of Literature and Journalism conducted in-depth interviews with 13 Chinese Gen Z nostalgia-core creators active on video streaming platform Bilibili. The researchers found that many of the interviewees shared a common desire to seek empathy as a buffer against loneliness. “Our generation, especially those who grew up in cities, spent much of our childhoods behind closed doors—somewhat isolated and lonely,” one participant described, adding, “We would spend a lot of time and energy noticing small details around us, like doors, windows, furniture, sounds, smells, and so on, fully immersed in the present moment. These details in my memories have thus become the traces of the era in my videos.”

Asked by researchers to describe what memories a specific image evoked, one interviewee zoned in on a KFC coupon, saying: “I grew up in Shenzhen. When I was little, my parents would occasionally treat me to KFC and McDonald’s. At that time, there were free coupons in front of the cash registers at KFC and McDonald’s…And their soda straws came in press-type dispensers.” Personal memory fragments such as these, when shared on social media platforms, have become keys to Gen Z’s collective memories. People flock to comment, as if participating in a digital wake for their childhoods.

Born during China’s one-child policy, most Chinese Gen Z grew up without siblings. They spent their childhoods alone, playing computer games or sitting in front of the TV, and many lack contemporaries inside the family to share memories of their upbringing with. Therefore, peripherals from this time have taken on special meaning and live on in them, resonating and embodying that carefree era. And while the technology of the past may not be as advanced as the smartphones we have today, they are vessels for memories of past lives.

Some point out that nostalgia-core is not only an act of remembrance, but a reflection on today’s world. “Our society has developed so quickly that it feels like we became adults in the blink of an eye,” Jiang, now 19, rues. “When under pressure, people instinctively seek out environments that make them feel safe. So looking back to childhood really reflects a kind of generational anxiety.”

Swept up in the irreversible march of time, some Gen Z seek comfort in the charms of such artifacts. In Zhu’s studio, the shelves are filled with retro consoles and old-fashioned TVs from the early 2000s, which he fires up at least once a week.

“It’s not like once you’re an adult, all you should do is work hard and hustle for a living,” Zhu emphasized. “You can still relax and play video games, pretend you’re a child for a little while.”