Despite localization’s key role in achieving success abroad, the industry remains misunderstood in China—something many linguists hope China’s first AAA game will change

Racing through bamboo, riding clouds, and traversing mountains, an armored simian takes on a host of formidable foes with his trusted golden staff, the Jingubang. No translation of the weapon’s name is provided, yet as the fights progress and it swings in full force, no further explanation of its inherent power is needed.

This is Black Myth: Wukong, China’s first blockbuster AAA game. Launched in August, it has topped global charts on gaming platform Steam since.

Inspired by the 16th-century novel Journey to the West, the game is being heralded as “China’s K-pop moment,” dovetailing a national drive to promote Chinese culture overseas—termed “soft power export”—and changing the government’s tune on video games, once disparaged as “spiritual opium” for the masses. The state-owned Cartoon Weekly went as far as to say the game “serves as a kind of ‘144-hour visa-free policy’ within the cultural entertainment industry,” proclaiming it as a means for the world to better understand the country from afar.

While many attribute this soft-power moment to Black Myth’s design and story, another crucial aspect of bringing the game overseas has been largely overlooked—translation and localization. Despite being key to a game’s reach and staying power, the process remains misunderstood in China and is often treated as an afterthought. Those in the video game localization industry hope that Black Myth’s success will bring a much-needed change.

What’s in a name?

Word choices can impact world-building and shape a game’s identity—something brought to the forefront in Black Myth, where several Chinese terms have intentionally been left untranslated.

Read more on Black Myth: Wukong

- Havoc in HR: How Chinese Workers Found a New Champion in ‘Wukong’

- Monkeying Around: Chinese Gamers on the ‘Black Myth’ Phenomenon

- Revisiting “Monkey,” Arthur Waley’s Artful Reimagining of a Chinese Classic

Mitch Lai, a Chinese-English localizer who has been working in game localization for six years, tells TWOC that such linguistic choices—in particular, the decision to retain the pinyin for terms such as jingubang (金箍棒), yaoguai (妖怪) and, of course, Sun Wukong (孙悟空) himself—play a big part in asserting Chinese identity.

“When a word unique to a culture gets anglicized, it can lose a lot of its cultural essence,” Lai says. “It stops painting a clear picture right off the bat. Take ‘kung fu,’ for instance—if we just call it ‘Chinese martial arts’ or ‘Chinese boxing,’ we strip away all the aesthetics and cultural depth that come with the term.”

According to a September article by Langlobal, one of the suppliers responsible for the game’s English translation, such linguistic choices were outlined in Black Myth’s style guide, written by the internal localization team at its developer, Game Science, which specifically instructed linguists to “retain the unique charm of Chinese culture.”

Lai points to similar decisions in other popular AAA games, like God of War Ragnarök, where the developers retained the Old Norse for some characters, such as “Jörmungandr” rather than the English “World Serpent,” encouraging players to learn the original name of this giant mythical sea snake.

“Without something as massive as Black Myth: Wukong, it could take years for these terms to catch on,” Lai says. “The developers absolutely made the right call. Whether it was [as the result of] confidence or just taking a leap of faith, I’m not sure, but it’s definitely brave.”

Due to a non-disclosure agreement, the English localization team for Black Myth was unavailable for interviews.

Translation and cultural identity remain subjects of hot debate in China, most recently with the translation of long (龙) as “loong” instead of “dragon,” to distinguish the creatures of Chinese mythology from what state media have described as “ferocious, fire-breathing Western dragons.”

“Choosing to use ‘loong’ instead of ‘dragon’ and ‘Wukong’ instead of ‘Goku’ is definitely a political move,” says Lai, referring to the Japanese name for the Monkey King popularized in the animation series Dragon Ball Z. “It’s a way of telling the world, ‘Hey, these terms have Chinese roots, and everyone should be calling them by their proper names!’”

Lai also points to unique challenges with the game, including all of its cultural, historical, and philosophical elements, which are rarely spelled out for the player. “The good news? The game doesn’t spend much time explaining the story—it’s all about the action,” Lai says. “The tricky part? They have to weave in all those intricate details without much room for explanations.”

Some gamers TWOC has spoken to attribute this lack of direct explanation to Black Myth being in the vein of soulslike games, a subgenre inspired by the Dark Souls franchise that emphasizes environmental storytelling to uncover lore.

Meanwhile, Vladimir Zhdanov, a content strategist and Russian localizer with over 14 years of game localization experience, explains that the delicate balance between cultural authenticity and ease of play can present unique challenges for localizing games with strong Chinese cultural elements. He says it’s something he’s seen change drastically over the course of his career, recalling an early localization project that also drew inspiration from Journey to the West, but scrapped its Russian version after developers deemed the story too difficult for players to follow, opting to rewrite it with fewer Chinese elements instead.

“It’s not only about localization itself. Rather, it’s how it was approached by the creators of the game, or the publisher,” Zhdanov says. “What’s their intention? Do they want to keep the ‘regional fire,’ or do they want to make it ‘mild spicy’ for us Westerners?”

Loc, interrupted

While Black Myth certainly sets new standards for localizing games with strong Chinese elements, the process of getting there reveals that Game Science and the greater Chinese gaming industry still harbor significant misunderstandings of what it takes to craft such a detailed, game-specific lexicon.

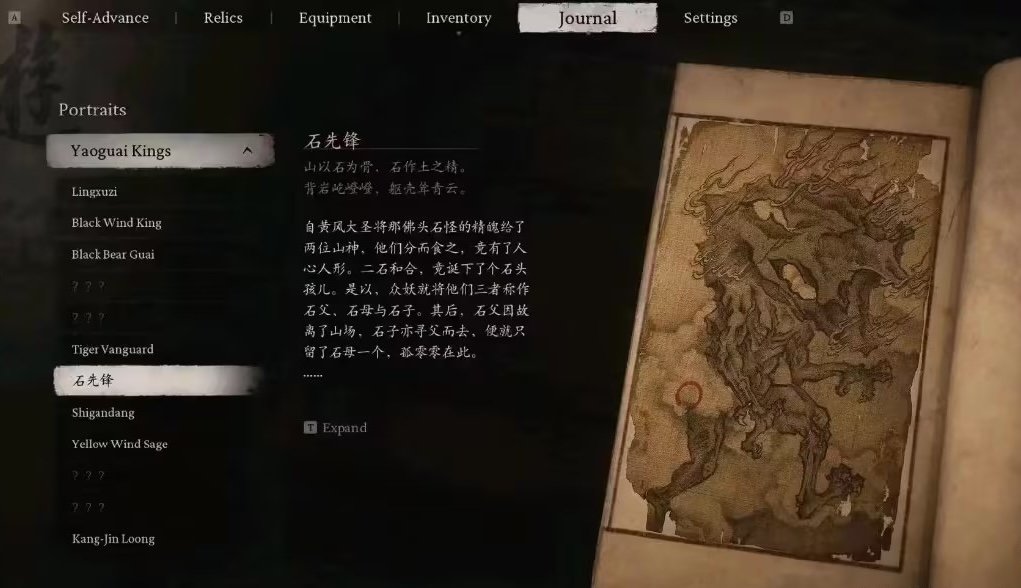

In an interview with Southern People Weekly magazine this August, the game’s controversial director Feng Ji pinpointed localization as a major challenge, admitting that the team “had a lot to learn” after underestimating the time needed to fully localize the game into 11 languages—a process that typically takes up to a year for AAA games. This miscalculation led to a time crunch, leaving large segments of the game untranslated in languages other than Chinese and English at launch. Early reviewers even shared screenshots of in-game journal entries detailing Black Myth’s various yaoguai still in Chinese, leaving gamers in the dark about these monsters’ backstories.

Evgeny Pakhalin, a Russian localization specialist who has clocked over 70 hours playing Black Myth, tells TWOC that due to gaps in translation, he was unable to play the game in his native language, instead switching to English.

“The [Russian] translation is great, but there are many untranslated parts,” Pakhalin says. “This is especially noticeable in crucial elements like the lore and story, which is unacceptable for an AAA game upon worldwide release. Good localization takes time, and whoever was responsible for the schedule and deadlines should have given the localization team more time to polish their work to perfection.”

At the time of writing, Pakhalin confirms that even after the latest patch, the Russian version remains incomplete, with, he estimates, around 30 sections displaying the message, “Our deepest apologies, this part is still being translated.”

However, Pakhalin praises the localization efforts he has seen so far, particularly the usage of a unified font across languages. He notes that this aspect is often neglected in other games, despite the on-screen text “working as a voice of the game,” and that when the fonts are inconsistent or unnatural, it can break immersion.

It’s details like these that many underestimate when it comes to game localization, assuming that the process and skills are akin to text-based translation in other mediums.

“The biggest hurdle has always been [others] thinking of translation as a simple, low-skill job. Until we shake off that misconception, China’s game localization industry is going to keep dealing with burnout, low wages, and crazy deadlines,” Lai says. “We might not be the ones crafting the story, but we play a key role in making sure it flows smoothly and keeps players engaged,” Lai says.

Behind the strings

Zhdanov explains to TWOC the immense effort and coordination required to bring a game as expansive as Black Myth into other languages. For instance, one language alone may require eight linguists, including language specialists, translators, and editors, along with localization managers and coordinators who facilitate communication between various teams. In Black Myth’s case, there are around 170 people credited for localization, though linguists TWOC has spoken to say this may not reflect the true scale.

“It is really complicated to maintain consistency,” Zhdanov says. “The biggest challenge is to take the work of several translators and make it a seamless experience.”

Unlike translators of books and movies, game localizers often work with an unfinished product that will continue to be updated even after launch, and not all types of script—snippets of which are often referred to as “strings” because of the way they are put back into the game’s code—are created equal. Even choosing a character or item name can be time-consuming as the linguists often don’t yet know how it will impact the game or other style choices.

“When you work as a localizer, you see two columns before you: source language and target language,” Zhdanov says. “If you’re lucky, you have the name of a character that speaks, but you don’t see their face. You don’t see what’s happening on the screen. So it’s a game of guessing, and imagination is the main asset for a localization specialist.”

Given all the moving parts and personnel, Zhdanov tells TWOC that it’s crucial for localization to be integrated into the game design process as early as possible, allowing potential issues to be flagged before it’s too late and too expensive to make changes. Even seemingly innocuous design choices made by game developers—for example, coding that assumes adding an “s” to the end of a word in any language will make it plural, text box designs that lack sufficient space for longer languages, or changing character genders based on the assumption of a neutral writing style for binary languages—can hold up the process. And this doesn’t even take voiceover work into account.

But for real change to happen in China’s localization industry, Zhdanov stresses that more game developers and producers must recognize that localization is hard work requiring more than just hiring a few international staff. They also need to be more responsive to feedback from linguists, rather than brushing them off and expecting a perfect translation. “I think they will learn from the experience [of Black Myth],” says Zhdanov.

Lai is also hopeful that Black Myth’s success could spark a wave of changes in China’s game localization development.

“With AAA games on the rise, I think China’s localization industry will finally get its chance to shine and earn the respect it deserves,” says Lai.

Lost in Translation: The Localization Challenge of “Black Myth: Wukong” is a story from our issue, “New Game.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.