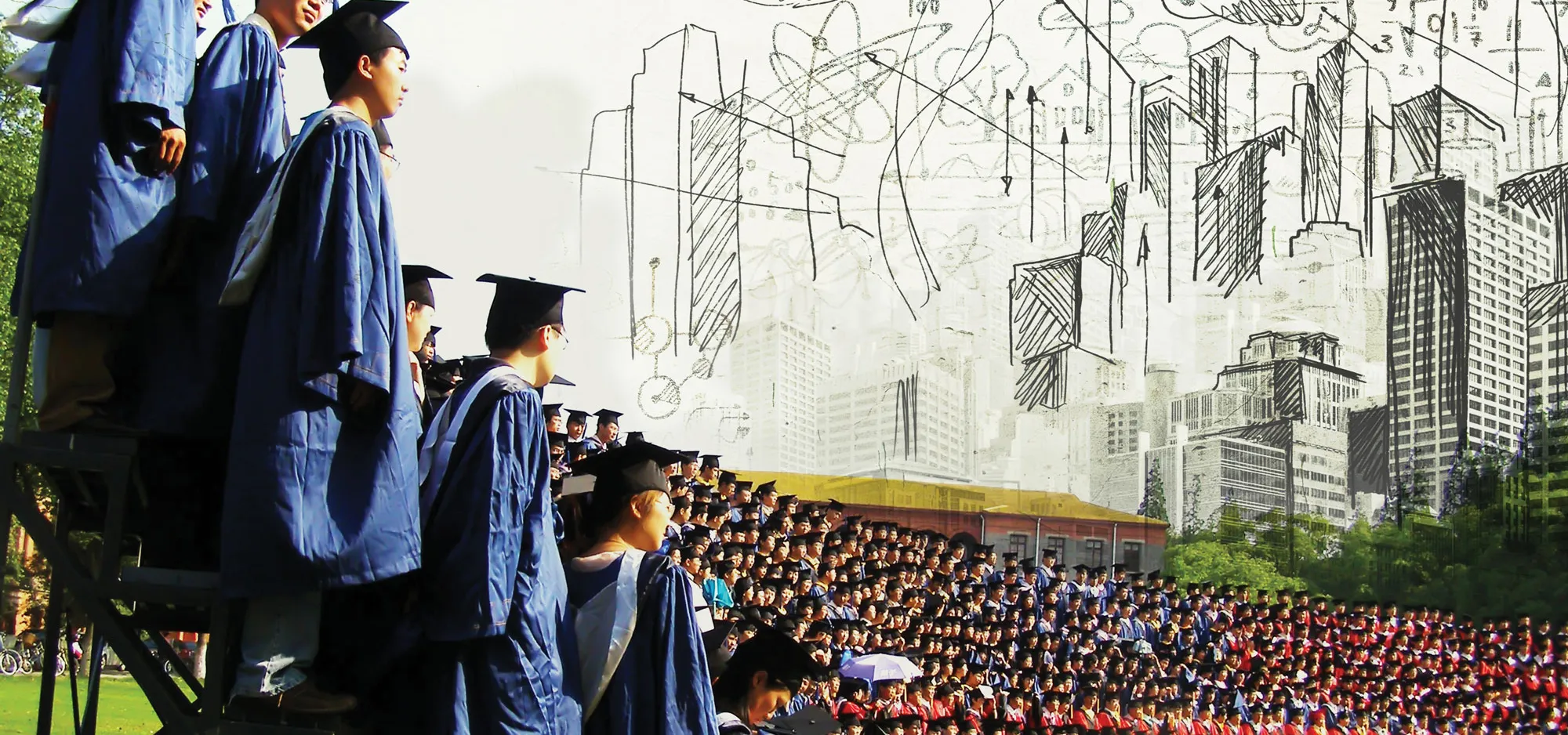

New graduates weigh the benefits and pitfalls of “slow employment”

At a campus fair, students armed with resumes prowl the crowded recruiting booths, searching for any sign of opportunity. But Guan Lingzi, 21, a senior majoring in banking and international finance at the Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, doesn’t join in the job-hunting fray. Instead, she is busy with her startup project.

During the summer holiday after Guan’s sophomore year, one of her friends exclaimed, “If only there was insurance for failed exams!” The joke was a catalyst. Just a week later, Guan and two friends launched a business through WeChat that offered students “exam insurance policies” at the price of 5 RMB. If the purchaser fails their next exam, they can get 30 RMB as compensation; but if they get good grades—like a 4.0-or-above GPA—they are rewarded with 20 RMB. It puts a whole new spin on gambling on your future.

The project grabbed attention when the entrepreneurs sold 100 policies in two days and, a few months later, Guan and her business partners were funded by their school’s entrepreneur program to the tune of 100,000 RMB.

“I didn’t attend any job fairs and don’t have any plans for further study. I have made up my mind to become an entrepreneur,” Guan told TWOC. “Even if my current project doesn’t work out and I have to find a job, I will come back to start my own business sooner or later.”

Guan Lingzi’s team meet to discuss their newly funded startup (Guan Lingzi)

In China today, more and more young graduates like Guan want to try their hand at starting their own businesses, rather than becoming desperate fodder for the increasingly impersonal and cutthroat job market. In popular discourse, they are known as the “slow employment” group. The “slow” refers to students who don’t opt for the fast-track to a job immediately after they graduate. Instead, they turn to entrepreneurship or freelance gigs in emerging industries, or just opt to take a gap year.

Opinions on these choices are divided. A commentary from Xinhua News Agency argued that using “slow employment” to describe graduates who have not found work is “self-deceiving,” stating that it is masking the problem of graduates’ difficulty finding a job. “No problems can be solved by creating a new concept,” Xinhua jeered.

There is good reason behind Xinhua’s concern. These people in the “slow-employment” group are not always there by choice. Statistics from the Chinese Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security show that there were more than 7.6 million college graduates in China in 2016, and the jobhunting population may be as high as 10 million.

But Yu Wenyang, 24, a graduate in petroleum engineering from the Chengde Petroleum College, disagrees. Before he officially graduated from college, he was offered a job in his own field at a factory. With regular working hours and a decent salary, it was an enviable prospect. But after a few months’ internship, he left the factory and became a member of the slow-employment group. “I don’t want a job in which I can foresee what everything will be like far into the future. I still have dozens of years to live,” Yu says.

Members of Guan Lingzi’s team prepare materials for a promotional activity (Guan Lingzi)

Leaving behind his “iron rice bowl,” Yu took a few months to figure out a new direction, eventually joining a Shanghai-based household chemical products company to become a door-to-door salesman. It’s not a prestigious job, but Yu loves it because he sees it as a stepping stone to becoming an entrepreneur. Every time he knocks on a door, he introduces himself by saying, “I am a student entrepreneur.”

“My own business is my final goal. According to our company’s system, if we do well at our position, we will be given an opportunity to run a branch office independently in a few years,” Yu says, trudging down the hall of a commercial building to knock on the next door. “It’ll be just like being the boss.”

The desire to become an entrepreneur is partly the result of a government push. “To foster a new engine of growth [in China], we need to encourage mass entrepreneurship and innovation and mobilize the wisdom and power of the people,” China’s premier Li Keqiang said at the 2015 World Economic Forum in Davos. Since December 2014, the Chinese Ministry of Education has been asking colleges and universities to grant students the option to suspend their education to pursue entrepreneurship. In a policy document, the MoE asked schools to “make innovation and entrepreneurship education a consistent element of the entire education process, and develop and offer courses dedicated to creativity and entrepreneurship.”

A live streamer broadcasting at an outdoor event in Shenyang, Liaoning province (VCG)

So far, more than 20 provinces and self-governing municipalities, including Beijing and Shanghai, have issued entrepreneur-friendly policies, some of which state that students who suspend their studies to pursue entrepreneurship may keep their student status for two to eight years.

Guan, however, warns students to think carefully before taking the leap. “The government encourages graduates to start up their own businesses because they want to solve the unemployment problem. But the students are the ones taking all the risks,” says Guan. While Yu is still basking in his entrepreneurial dream, Guan has already learned that entrepreneurship isn’t an easy road. “As university students, our horizon and knowledge about the industry is limited. We lack business connections, experience, and most importantly we lack money. In most cases, when the investors know you are a new graduate, they won’t consider investing in your business,” says Guan. “If you choose this path, you need very strong internal motivation.”

Luo Rui, a junior majoring in investment at the Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, who is now running a café on campus, is also wary of the pitfalls of this path. “From what I’ve seen, most entrepreneurs have seven or eight years’ experience in a certain industry. Venture capitalists can hardly really be interested in an inexperienced student’s startup,” says Luo.

Luo’s café opened in February 2016, supported by the school. Though its average monthly sales have reached 13,000 RMB, a pretty good performance compared to others funded by the school’s student-entrepreneurship program, Luo says being a business-owner isn’t in her longterm career plan, opting to call herself a “parttime entrepreneur.”

“I think one of the main differences between an entrepreneur and an employee is the ability to take risks. It’s still too risky to become an entrepreneur. For me, entrepreneurship is just a good way to gain more knowledge and experience about the industry and society. Even if I do eventually launch a business, now is not the time. I will find a job or turn to further study after graduation. After all, that’s a path 80 or 90 percent of students have chosen,” says Luo.

But even among those who stick to the tried-and-true route of employment after graduation, attitudes and career aspirations are quietly starting to change. A survey based on user data collected from the QQ web browser, 54 percent of participants from the “post-1995” generation chose “internet celebrity” as their ideal job, followed by voice actors, makeup artists, and cosplayers. Server, office clerk, and public servant were the least popular jobs. Stability no longer has the draw it once had.

Examinees at Nanjing Forestry University wait to attend the 2017 Civil Service Exam (VCG)

For the parents of this generation, working for the government or in a state-owned company was the ideal career choice because it was a decent, stable job for life. While it seems that these positions are waning in popularity today, even fairly low-paying civil service jobs can sometimes see tens of thousands of applicants.

With more than 1.3 million people registering for the 2017 national civil service entrance exam, it’s hard to say that public service jobs aren’t in demand, but, at the same time, a total of 223 posts ended up with no applicants. The main causes may have been the high requirements and fierce competition of civil service, but, in the eyes of many young people, stability isn’t nearly as important as prestige and cold hard cash.

Online jobs have become another key career avenue. WeChat stores, live-stream broadcasters, and daigou, who buy products overseas to resell online, are popular career choices. Li Jianing, a 21-year-old, who graduated last year from a college in Shenyang, Liaoning province, recently started a WeChat business selling teeth-whitening items. She cultivates a well-developed WeChat presence with plenty of ads in the form of photos and videos. She is also learning to improve her makeup skills and planning to be a live streamer.

“My mom wants me to take the civil service entrance exam because she thinks it will be a stable, decent job. But I feel that it’s boring. In my opinion, any job can be decent. You work and you make a living,” says Li. “I want to do something that I am interested in and where I have more freedom.”

“I know that maybe I am not pretty enough to be a live streamer, but honestly, I feel I am not smart enough to pass the civil service exam either. There is no easy work in the world, right?” Li adds. “But maybe I will take the provincial public service exam because if I fail, my mom will have nothing to say.”

Taking a “gap year” is another option for “slow employment” graduates, and was Chinese youths’ fifth most popular choice according to the QQ survey. Li Liang graduated in 2011 and took a gap year to travel around the country. During the trip he became interested in photography and, upon his return, opened his own photo studio.

Years later, more and more graduates are taking Li’s path. At the end of 2014, the China Youth Development Foundation, a national public foundation based in Beijing, set up The China Gap Year Foundation to help to promote the idea of the gap year as a legitimate post-graduation choice. It is the first domestic organization to provide financial support for 18 to 28-year-old students to pursue gap year activities in China or internationally for three months to one year.

“Such experience has indeed influenced young people’s career decisions. Some find interest in new fields and see more possibilities in their future careers. Others feel lost when they come back from their gap year, and find it difficult to get their life back on track,” says Gu Zhengzheng, a spokesperson for the Gap Year Foundation. “It brings different things to different people, but generally it’s positive.”

Gu says that in 2015, there were around 100 applicants, and in 2016, the number increased to more than 200, but it’s still below their expectations. The gap year is not yet very popular in China, and many worry that it causes young people to miss job opportunities, or that it is an excuse for slacking. Gu disagrees. “The [gap year] concept is ahead of the level of [China’s] social development, even a little bit against tradition,” she argues. “Many young people can’t gain approval from their family and face tremendous pressure. So far, it’s still just developing in a small crowd.”

The challenges faced by the new generation of grads are new, but so too are the opportunities. Be they willful entrepreneurs, hopeful live streamers, dutiful would-be civil servants, or wishful gap year students, it’s undeniable that even as the “slow economy” grads grapple with societal pressures today, their values toward work-life balance will shape the experience of a future generation who will look to them as career trailblazers and employers—when they finally get there.

The Grads Are Alright is a story from our issue, “Taobao Town.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.