The female pioneers of China’s film industry and how they’re continuing to bring important, fresh perspectives to the big screen

China’s film industry may still be male-dominated, but for now, the country’s most famous director is a woman. Jia Ling’s latest film, YOLO, soared during the Lunar New Year holiday, raking in over 3.4 billion yuan at the box office. The film, which Jia starred in, is an uplifting story of an obese and suicidal protagonist who learns to love herself. Jia shed 50 kilograms for the film, which also made her just the fourth female Chinese director to make an accumulated 10 billion yuan at the box office over their career.

Her previous hit, Hi, Mom (2021), was another huge success. The film, based on the life story of Jia’s mother, an ordinary factory worker during the 1980s, was a breath of fresh air to viewers. Jia has mastered the art of character development, breaking gender stereotypes, and bringing new perspectives to audiences. But she isn’t the only woman filmmaker who has shattered prejudices and the glass ceiling in China’s movie industry, which is slowly becoming more populated by women. Here are some of the female pioneers of China’s film industry who have made cinema richer and more diverse:

Huang Shuqin (黄蜀芹)

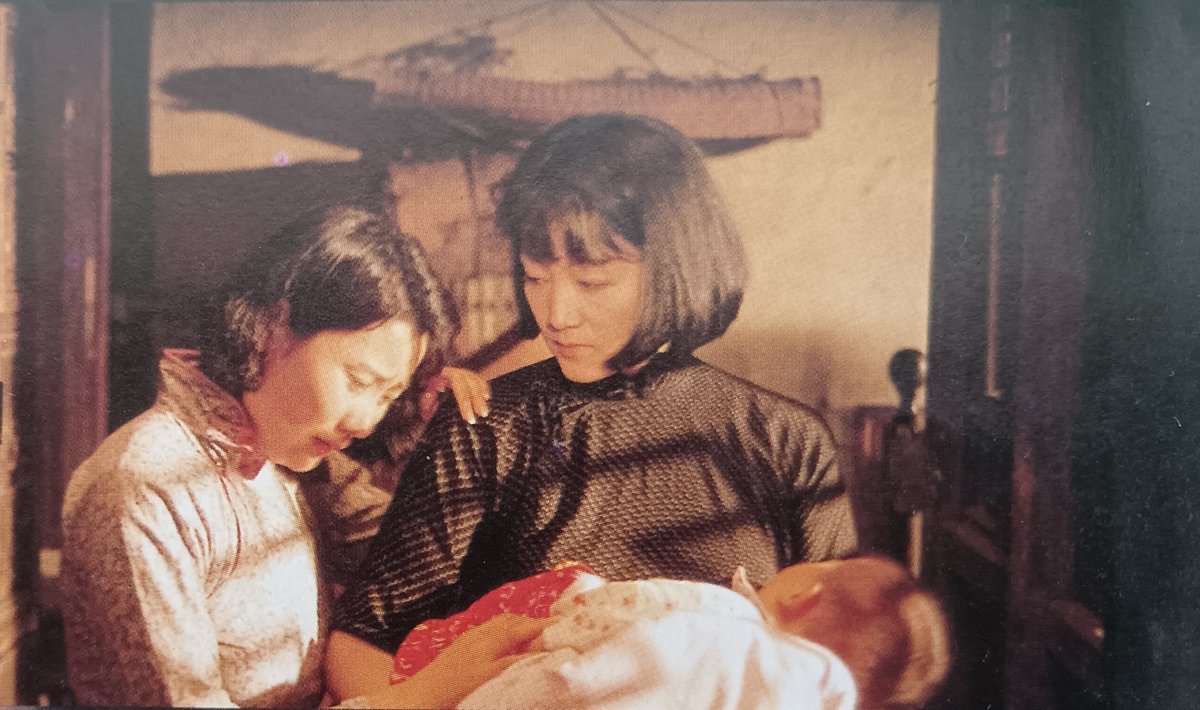

Huang was a leading figure of China’s so-called “fourth-generation” directors trained in the 1960s and ’70s. Her eight films and three TV shows often explored the dilemmas of contemporary women. Her 1987 movie Woman, Demon, Human, based on the life of renowned opera performer Pei Yanling, is regarded by scholar Dai Jinhua as China’s first feminist film. Woman tells the story of teenager Qiu Yun (Xu Shouli) as she struggles with her female identity while building an opera career playing only male roles. In playing Zhong Kui, a fierce Daoist deity who tames evil demons, Qiu escapes and rejects her womanhood and seeks salvation in an idealized male figure. “It [the film] is about expression and silence. It’s the story of a real woman and her fate, but also a symbol of women, especially contemporary women’s historical fate,” Dai wrote in her essay “Woman, Demon, Human —A Woman’s Dilemma” published in Shanghai Literary Theory in 1992.

In 1994, Huang’s A Soul Haunted by Painting starring Gong Li continued her exploration of female perspectives by telling the true story of early 20th-century artist, Pan Yulian. Sold into prostitution at a young age, Pan married an official and later trained in painting and sculpture in Paris and Italy. But when she returned home as a pioneer female artist, the past came back to haunt her. Huang, who died in 2022 aged 83, was a trailblazer for Chinese films by and about women.

Ann Hui (许鞍华)

Hong Kong director Ann Hui’s career spans almost five decades and genres from thriller to martial arts and romance to family drama. She led the Hong Kong New Wave movement in the late 1970s when she, along with a group of young filmmakers, adopted modern technology and cinematic perspectives in filmmaking, while focusing on social issues. Her feministic and humanitarian perspective started to form in her semi-biographical 1990 film Song of the Exile, in which a daughter reexamines her relationship with her distant mother after they take a trip together. Based on Hui’s own mother, a Japanese expat living in Hong Kong after 1945, the depiction of cultural alienation, internal struggle with national and personal identity, and hardship as a new immigrant have struck a chord with a generation of Hong Kong audiences.

Ann Hui’s most celebrated feminist work is perhaps Summer Snow (1995). In this comedy, May (Josephine Siao), who is in her 40s, copes with challenges at work, while at home, her son and husband provide limited support in daily chores. After her mother-in-law passes away, May has to take care of her father-in-law, a bad-tempered former military pilot, who starts to show symptoms of dementia. After much stress and misunderstanding, May and her family rediscover strength in one another. The vivid portrayal of a crisis-afflicted woman, an ordinary family going through upheaval, and broader Hong Kong society in transformation made the film a timeless classic. The film won the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1995, and six Hong Kong Film Awards in 1996, including Best Picture.

From July Rhapsody (2002) to The Postmodern Life of My Aunt (2006), The Way We Are (2008) to A Simple Life (2011), Hui’s best work focuses on individuals confronting social transformation. She is also an innovator, often experimenting with genre and style (not always successfully).

At the age of 77, Hui remains an active filmmaker churning out an astonishing one or two films a year.

Li Shaohong (李少红)

One of the leading figures of “fifth generation” directors trained in the 1980s, Li is much less celebrated than her male peers like Zhang Yimou or Chen Kaige—she deserves more recognition. Li, a soldier before she went to film school, didn’t start by exploring feminist themes. Li’s debut film is the 1988 cult thriller The Silver Snake Murders, a violent feature full of shots of women that would today be described as typical “male gaze.” In a workshop she taught during the Hainan Island International Film Festival in 2022, Li explained her early filmmaking experience: “Our generation had experienced the self-wakening. We went through our youth with the [common official] slogan ‘Women hold up half the sky,’ and felt we could do everything men could. But that actually blurred gender difference.”

Signs of Li’s feminist awakening emerged in her film Bloody Morning (1992). This rural tragedy follows Hongxing (Kong Lin), a young woman who is driven home by her husband after he notices the absence of bleeding from Hongxing on their wedding night. The shame is too much for Hongxing’s two brothers, who accuse the village teacher of taking their sister’s virginity and murder him in cold blood. The film never addresses the truth of Hongxing’s virginity, but instead focuses on the ignorance and absurdity of the construct that led to the tragedy.

Li’s most acclaimed film, Blush (1995), follows two prostitutes sent to reeducation through labor in the 1950s. Adapted from a novella by Su Tong, the movie sees Li switch from a societal angle to focus entirely on the fate of these two women. Blush was a domestic box office success, making 28 million yuan from a budget of just 2.5 million yuan.

Li also brought new perspectives to TV. Her show Palace of Desire (2000) took on the reign of China’s only female emperor Wu Zetian (who reigned from 690 to 705) and the complicated relationship with her daughter Princess Taiping. In this innovative work, Li also invented a unique style of dramatic language in which modern Chinese takes on Shakespearean influence. In Li’s telling, women are every bit as ambitious and ruthless as men in the power struggle at the center of the Tang empire. After a tantrum by one of her male concubines, Wu Zetian says: “A man, when placed into the circumstances of a woman, becomes a woman,” no doubt an adaption by Li of an observation by French philosopher and feminist Simone de Beauvoir: “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.”

Li has long advocated for female expression and perspectives in Chinese films. As the president of China Film Director’s Guild, in 2015 she launched the CFDG Young Director Support Program, one of the most important annual avenues in the Chinese film industry to discover and nurture young film talent.

The New Generation

The contemporary female director scene is more diverse than ever, and these filmmakers are taking on a range of new themes. Young female directors have focused on mother-daughter relationships, female sexual desire, sexual abuse, and domestic violence, all themes previously skewed or underexplored in China’s film industry.

Yang Lina, born in 1972, has explored many of these topics. In Longing for the Rain (2013), a middle-class homemaker is haunted by sexual dreams and turns to Daoism for salvation. Then, in Spring Tide (2019) and Song of Spring (2022), Yang explores the cruelty and selfless love in a complicated mother-daughter relationship.

To some female directors, making films is not only artistic expression but a healing process. Director Huang Ji grew up in a rural part of Hunan province as a “left-behind child” living with her grandparents while her parents moved to faraway cities for work. Huang started dating out of loneliness and suffered sexual exploitation. Her films Egg and Stone (2012) and The Foolish Bird (2017), were inspired by her personal experience. Starring amateur actress Yao Honggui, whom Huang discovered in a local school in her hometown, the two films follow the teenage girl as she navigates isolated small-town life and relationships.

In a director profile video produced by Yitiao for the Xining FIRST International Film Festival in 2017, Huang expressed the critical role of filmmaking in her life: “If it wasn’t for making films, I would have carried lots of heavy burdens. By shooting films, I unload them with support from the bravery and strength of many others along the way. I’m so thankful for the movies.”