White-skin worship and whitening remedies in Chinese history

Umbrellas on a sweltering day. Adverts for whitening treatments. Middle-aged women swimming in head-to-toe wetsuits and face-kinis. Yes, it’s summer in China, and everyone’s trying to get the perfect beach body: White, ideally the palest possible shade.

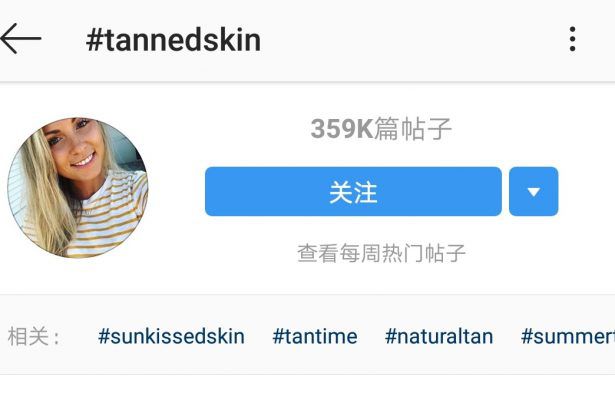

It’s a stunning contrast to the tanning salons and treatments attracting millions of hashtags on Instagram, as Western influencers try to copy the bronzed appearances of their latest idol via spray tans and sun beds.

#tannedskin: nearly 360,000 discussions

In China, where dark skin is still broadly associated with manual labor and low socioeconomic status, looking as coral-white as Fan Bingbing is the aesthetic standard to aspire to. If you are a successful woman, you are expected to be pale, rich, and beautiful (白富美).

This is not a recent phenomenon. The Book of Songs (《诗经》), a collection of verses dating back to the 11th century BCE, rhapsodize about “white soft hands and smooth pale skin (手如柔荑,肤如凝脂)” in “The Duke’s Bride” (《硕人》). Skin color was already a broad indicator of social status by the time of the Han dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE), according to records from that time; those who enjoyed a life of luxury and leisure tended to stay indoors or in the shade, while the lower orders tanned as they toiled in the fields and rice paddies.

Those who want to escape this grim lot might well choose to lighten their appearance, usually by using traditional (and toxic) Chinese prescriptions, such as the “four white creams” (四白膏) in the Tang dynasty Qian Jin Prescriptions (《千金药方》) or “jade-skin powder” (玉容散) from the Ming dynasty’s Puji Prescriptions (《普济方》) . The “four white creams,” proposed by “divine physician” Sun Simiao’s (孙思邈), is a combination of three herbs—herbs Angelica dahurica, Ampelopsis japonica, and rhizoma typhonii—and dead silkworms. “Jade-skin powder,” which also uses a mixture of herbs and crushed pearls, was beloved by Empress Dowager Cixi of the Qing dynasty.

Even as Chinese aesthetics changed in terms of weight, figure—even eyebrow shape— throughout history, the standards for skin color remained mostly constant. Paleness was the shared characteristic of ancient beauties as diverse as the willowy Xi Shi (西施) of the Spring and Autumn period, the voluptuous Concubine Yang (杨玉环) in the Tang dynasty, the strong-browed Zhuo Wenjun (卓文君) of the Western Han dynasty, and the ethereal Lin Daiyu (林黛玉) of Dream of the Red Chamber. In his memoir Recollections of Dreams in Tao’an (《陶庵梦忆》), Ming dynasty writer Zhang Dai even suggested that “white skin cover a hundred blemishes” (一白遮百丑), which is still a widely used proverb today.

Tang beauties were known for being voluptuous (but still pale) (VCG)

However, in the 1960s and 70s, class struggle became the only fashion, and Cultural Revolution role models like Xing Yanzi, a Party member who went to work alongside the peasants, reflected the masculine ideals of that time–short hair, dark skin, and strong personality.

But it didn’t take long for the Chinese to start loving light skin again, and embrace new remedies, known as 美白 (“beautifying white”), to help them achieve it. In recent years, Chinese actress have tried to lighten themselves by “whitening injections” and smearing face-whitening creams on the whole body.

Today, there are small signs of change. Tanned singers Tan Weiwei and Jike Junyi (who is of the Yi ethnicity) enjoy successful pop careers, and are noted for being good-looking “despite” their skin tone. Last year, the first season of TV talent competition Produce 101 saw the rise of dark-skinned Wang Ju, who ranked second out of 101 candidates, and was much beloved on social media for challenging conventions. There’s hope yet for a more inclusive type of beauty ideal in China.

The kids are all white: Produce 101 contestant Wang Ju is one of those challenging aesthetics (Tencent)

Updated 2019-06-26

Cover image from VCG