Faced with mounting pressures from overseas tariffs and dwindling labor and growing competition at home, the future of the city’s decades-long dress trade hangs in the balance

“This gown costs about 300 US dollars from the factory, and about 3,000 US dollars to buy in a big brand store abroad,” says Mr. Chen, head of the Yunshang Clothing Factory in Chaozhou, Guangdong province, as he shows off the latest dress design in his factory office. A moment later, Chen’s British Shorthair stretches a paw toward the dress, causing him to rush over and carry the cat hastily out.

Outside, the workshop buzzes with noise. Among fabrics of every color piled on the floor and finished gowns hanging on horizontal bars, the factory’s predominantly female workers busily wield irons spewing steam, cajole an array of sewing machines, and painstakingly fix tiny beads onto dresses. They’re up against the clock to complete this spring quarter’s orders, which must be finished and sent overseas before the upcoming Chinese New Year.

There are over 1,000 such wedding and evening dress production-related enterprises in Chaozhou, employing around 100,000 people. Of the approximately 20 million dresses produced here annually, nearly 90 percent are bound for international markets. In 2004, the local industry was already so established that the China National Textile and Apparel Council and the China National Garment Association awarded Chaozhou the title of “China’s Famous City of Wedding Dresses and Evening Dresses.”

Read more about the evolving landscape of manufacturing in China and the lives of its workers:

- In Southern China’s Once-Thriving “Garment Kingdom,” Business Fades Amid Urban Renewal

- Why China’s Gen Z Migrant Workers Are Leaving the Assembly Line

- Viral Hinterland: The Famous Chinese County That No One Visits

But Chaozhou’s dress success began in earnest more than 40 years ago. After China’s economic reform and opening up in the 1980s, the city’s largest textile factory, the Chaozhou Embroidery Factory, brought contract manufacturing, specifically of beads, to the area. Then, thanks to the industry’s relative maturity, between 1990 and the early 2000s, a growing number of wedding dress and gown companies from Europe, the US, and the Middle East chose Chaozhou as their main supply base.

It was during this period that Eva Wang, Mr. Chen’s wife and co-owner of the Yunshang Clothing Factory, built her network and industry knowledge. After graduating from university, she worked in the Chaozhou office of a Middle Eastern bridal wear company for seven years, before deciding to open her own factory in 2007.

“Chaozhou’s irreplaceable advantage is its people; they’re excellent at doing these fine bead embroideries,” Wang tells TWOC.

A thread through generations

This cultivation of talent in Chaozhou has a long history, predating the rise of its modern-day dress industry by centuries. Records from the Guangdong Cultural Center show that there were more than 5,000 professional embroiderers in Chaozhou during the Qianlong emperor’s 18th-century reign, with regular garment exports made to Southeast Asia at the time. These skills culminated in a style that came to be known as “Chaozhou embroidery”—intricate stitching used to create openwork floral designs. The most exquisite pieces adorned statues of the gods during the region’s annual Chinese New Year-adjacent Pageant on Immortals, as well as Teochew opera performers and participants in the local Yingge, or “Hero’s Song,” folk dance.

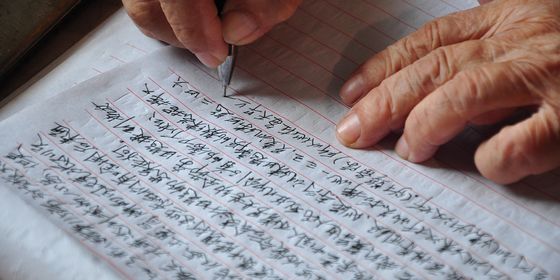

This history and the thriving industry have helped jointly promote the development and popularization of embroidery in the region. Most girls are taught how to embroider by their mothers, not only in Chaozhou, but also in areas further afield.

Chen Xiuling, a 60-year-old female worker, typifies this phenomenon—she is one of Yunshang Clothing Factory’s most experienced seamstresses. Since a young age, she has made a living doing beadwork, and entered the wedding dress industry 20 years ago. “I am in charge of the bead embroidery part of the dress samples in this factory because it’s a more intricate element. There are very few female workers today who know ‘Chaozhou embroidery’ like I do.”

Even today, the most time-consuming, tedious, and delicate beadwork in Chaozhou is subcontracted to local women, many of them housewives, through specialized intermediaries, just as it was 200 years ago.

Because it is becoming increasingly difficult to find enough women in urbanized areas who are still willing to do the work, this particular quirk of Chaozhou’s dressmaking industry is now at risk. “Now these materials need to be sent to more distant places like rural villages,” Wang explains. “The older generation of workers who can bead by hand don’t really want to do it anymore, and there aren’t many young people who are willing or have the patience to do this kind of work.”

“So now a lot of the beading process is done by machines,” Wang continues. “But machines can only do simple beading. Wedding and evening dresses are very delicate things, and machines aren’t as dexterous as human beings.”

If the technology doesn’t catch up, factories that are unable to replenish staff may soon be left empty-handed. In the several factories TWOC visited, workers are aged around 40 to 50, with the youngest still above 30.

An industry hemmed in

“Almost all the dresses produced in this factory will be sent to Los Angeles, USA,” said Li Chuxian during a visit to one of three factories owned by Pretty Lady Wedding Dress Co., one of the largest wedding and evening dress companies in Chaozhou. Li, the 24-year-old daughter of the factory manager and overseer of order management, ensures that its 100,000-plus dresses produced every year—40 percent of which are commissioned by American clients—make it to their destinations safely.

Six hundred meters away, on a street dubbed by locals as the “Wedding Dress Street,” sit Pretty Lady’s and Yunshang’s offices. This 400-meter-long stretch was once home to about 20 wedding photography shops and six dress factories. Now, however, only five wedding photography shops remain.

Zhan Jianpeng, the founder of Pretty Lady and vice president of the Chaozhou Wedding Dress and Evening Dress Industry Association, entered the industry in the 1990s, starting out as a Hong Kong wedding dress company’s head of production in Chaozhou. Using the knowledge he gained from that position, he established Pretty Lady in 2004.

Another veteran from Chaozhou’s halcyon days is Qiu Yangcai, 42, owner of the Hexin Garment Factory. “The most glorious time for the industry in Chaozhou was from the 1990s to the early 2000s, and it started to go downhill after 2010,” Qiu says, adding, “At that time, there were so many orders from every country, and each order’s price was high. Clients would accept all the designs, and every factory could get many orders and make high profits. It was a crazy time.”

In recent years, with the global economy generally in the doldrums, demand in major overseas markets such as the US and Europe continues to slump. The rapid development and lower prices in up-and-coming manufacturing hubs, such as those in Southeast Asia, have led some foreign companies to take their business elsewhere, especially in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. Although the situation began to improve in Chaozhou after 2023, it has yet to bounce back to pre-2019 levels.

“Last week, the local government organized an industry meeting with five big local companies,” says Zhan. “The companies’ representatives all said their sales dropped in 2024, while only ours grew a little.”

“With the decline in orders, the most intuitive change is that the styles become simpler,” says Ms. Ning, Pretty Lady’s sales manager. “Simple styles are cheaper.”

The Trump effect

According to Research and Markets, the US is the world’s largest wedding and evening dress market, valued at about 27 billion US dollars and accounting for 44.16 percent of the global total value. But exports to America are becoming fraught with risk and uncertainty for makers in Chaozhou, a development that is particularly concerning given the vast majority of their products are shipped overseas.

Then, on January 20, 2025, Donald Trump was inaugurated as President of the United States for the second time. During his campaign, he vowed to increase tariffs on all goods from China by up to 60 percent, apparently including bridal evening gowns. On February 1, Trump announced his first round of additional tariffs, including a 10 percent increase on clothing from China, which in some cases totaled around 35 percent.

“Forget a 60 percent tariff—I can’t even afford a 20 percent,” Zhan tells TWOC. “My profits aren’t that high.” But despite the policy, he isn’t terribly worried. “First of all, the depreciation of the Chinese yuan will offset some of the impact, although not completely solve it.” (The yuan has traded as high as 7.009 against the dollar over the past six months and is currently at a weaker point of 7.28.)

While earlier reports indicated that Chinese factories received an uptick in orders from US clients who rushed contracts to avoid possible Trump-backed tariffs, Ms. Ning refutes this account. “Dress styles are seasonal. If customers place more orders, they’ll be left with a backlog of inventory because individual styles aren’t popular for a whole year.”

Ms. Ning also relays the story of an interaction she had with an American wholesaler and his team who visited the factory in November 2024, after the results of the US election were announced. While browsing the newest styles, the all-white group candidly revealed that they had all voted for Trump. When asked if he was concerned about the potential impact of Trump’s tariff policies on sales, the wholesaler said they didn’t bother him and that he believed business would be good during Trump’s second term. He added that if tariffs were enforced, he’d simply raise prices and make the consumers pay the difference.

No matter what happens in the next four years, both Zhan and Qiu intend to stand firm. “I’ll still sell my products at the original price, and if that doesn’t work, I won’t accept orders. American clients will figure out how to deal with the increased tariffs by themselves, and in the end, it will be the consumer who pays.”

This appears to be the case, except where both the procurers and the customers are unwilling to foot the extra bill. “This quarter, I offered 50 styles to American clients, but none of them placed orders because they didn’t know what the final price would be,” Qiu says. Wedding dress orders from the US account for 60 percent of his factory’s overseas orders.

Little wiggle room at home

In the face of dwindling American business and an uncertain foreign trade environment overall, many dress factories in Chaozhou have considered trying to break into the domestic market—but few have succeeded.

Every afternoon, Eva Wang livestreams and attempts to sell her products on Douyin, China’s version of TikTok, despite believing that the domestic market will never be important for the success of her factory. “Domestic consumers not only have a low spending capacity generally, but they are also very picky.”

The Chinese clothing market has long been dominated by online shopping channels, a situation that has created oversized expectations when it comes to after-sales services. Reports suggest that the refund rate for some female clothing in China is as high as 80 percent, making it impossible for some less well-equipped companies to survive. “When it comes to delicate and easily damaged wedding and evening dresses, this [the high chance of returns] is unacceptable,” Wang says.

The need for such clothing, and therefore the development of the industry, is also hindered by cultural differences. Wedding and evening dresses aren’t typically worn in China, and now also face competition from the rise in popularity of traditional, homegrown clothing trends such as hanfu, traditional clothing of the Han ethnic group, and xiuhefu, based on Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911) wedding attire. “In China, people only consider wedding dresses or evening dresses when they get married. But in the West, evening dresses are a fixture,” Zhan says. “So the domestic market is relatively small.”

Another major challenge affecting Chaozhou’s ability to get a foothold in the domestic market is the rivalry from factories in China’s eastern city of Suzhou, Jiangsu province. Unlike Chaozhou, Suzhou’s garment factories have a long history of dominating the domestic market through relatively cheap products. “The cheapest Suzhou wedding dresses are available for 100 to 200 yuan, but those are simple styles. Chaozhou wedding dresses are generally more finely crafted and cost 500 to 600 yuan or more,” Ms. Ning explains.

Meanwhile, Qiu Yangcai has a more hopeful outlook, having tasted the sweetness of the domestic market. Since the second half of 2022, when the slump in foreign trade meant the domestic market began to open up, half of his factory’s orders are now bound for sellers around China.

“The domestic market is changing fast, and it is full of competition. Everyone wants a slice of the cake,” Qiu says. Despite this, he believes that Chaozhou factories still stand a chance in the domestic market, given its sheer size and the number of orders that need to be fulfilled. Nevertheless, he said his success remains grounded in the superior quality of Chaozhou dresses: The ex-factory price of some dresses produced for domestic clients is around 800 yuan, which is more than even the price of some foreign orders at other factories. “We don’t take orders for low-end products. Our model doesn’t allow us to fulfill low-price orders in bulk.”

The proof is in the product

When asked if they were concerned about competition from factories in developing regions like Southeast Asia, all three factory owners said they didn’t consider it a threat. They believe the workers there lack the skills of those in Chaozhou and are only able to produce simple styles.

Wang specifically points to the premium customized services her Yunshang Factory provides for European, Middle Eastern, and American companies, including pieces for the fashion designer and dressmaker Sherri Hill. These bespoke orders mean that while individual runs aren’t particularly large, with quantities ranging from dozens to hundreds of pieces, the ex-factory price for each dress can ring in at over 100 US dollars on average.

“Another advantage of factories in Chaozhou is flexibility. The factories here are generally not too big and can survive even if the number of orders is small. Mechanized production, on the other hand, requires large order quantities, something that cannot be achieved with premium products,” Wang explains, adding, “In the future, there will be fewer and fewer workers in this industry, and the products will become more and more expensive and premium.”

Brushing off such concerns, Wang, like any Chaozhou businessperson worth their salt, beckons TWOC reporter instead to savor the freshly brewed tea she’d prepared, urging simply, “Drink, drink.”

Photography by Arthur Wei

Amid Snags in Global Trade, Chaozhou’s Wedding Dress Factories Battle to Survive is a story from our issue, “Youthful Nostalgia.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.