China’s adherence to the 12-year zodiac cycle is known around the world. What might be more surprising is that the West’s astrological signs have also existed in the country, possibly from the very beginning.

Comparing horoscopes is one of the most popular icebreakers in China today. In search of common ground, people offhandedly bring up the pickiness of Virgos, the diligence of Capricorns, or the frugality of Tauruses. What’s less commonly known, however, is that discussions of the 12 Western astrological signs are far from a recent import—they have been in China for hundreds, even thousands, of years.

China developed its own constellation system as early as the fifth century BCE. Known as the Three Enclosures and the Twenty-Eight Mansions, this system divided the night sky into 31 sections to locate various celestial bodies. A total of 283 constellations, referred to as “officials,” were used to foretell auspicious or ill-fated events, predict human destinies, and correlate with the prosperity or decline of different regions and cities. Knowledge and interpretation of astronomical phenomena were reserved for the imperial court or religious authorities.

Archaeologists have hypothesized the existence of at least some of the 12 astrological signs in China as far back as the Three Kingdoms period (220 – 280), a century after the Alexandrian astrologer and astronomer Ptolemy had published his Tetrabiblos, which continues to form the basis of Western astrological tradition today. In 1978, a bronze mirror from the third century was unearthed in Guangxi. The mirror did not only feature celestial imagery but also depictions of crabs and jars—speculated to represent Cancer and Aquarius.

Read more on ancient Chinese astronomy:

- Badass Ladies of Chinese History: Mathematician and Astronomer Wang Zhenyi

- Why Were Ancient Chinese Emperors Afraid of Mars?

- A Brief History of the Solar Eclipse

Although there is no archaeological evidence that Western horoscopes were in China at this time, ancient trade routes between the Greco-Roman world and China opened as early as the first and second centuries BCE. The 12 zodiac signs, which were invented in Babylon before this time, could very well have made their way to China through traders.

The spread of Buddhism played a pivotal role in introducing Western zodiac concepts to ancient China. By the second and third centuries, Greek astrology had entered ancient India through various Sanskrit translations and was incorporated into Hindu and Buddhist traditions. In China, the earliest complete reference to the 12 zodiac signs dates to the sixth century, when the Indian monk Narendrayaśas translated The Sutra of the Perfection of Wisdom (《大方等大集经》) from Sanskrit to Chinese. In this sutra, 12 deities were associated with each month, with figures like the “Crab God,” “Lion God,” and “Scorpion God” as early representations of Cancer, Leo, and Scorpio.

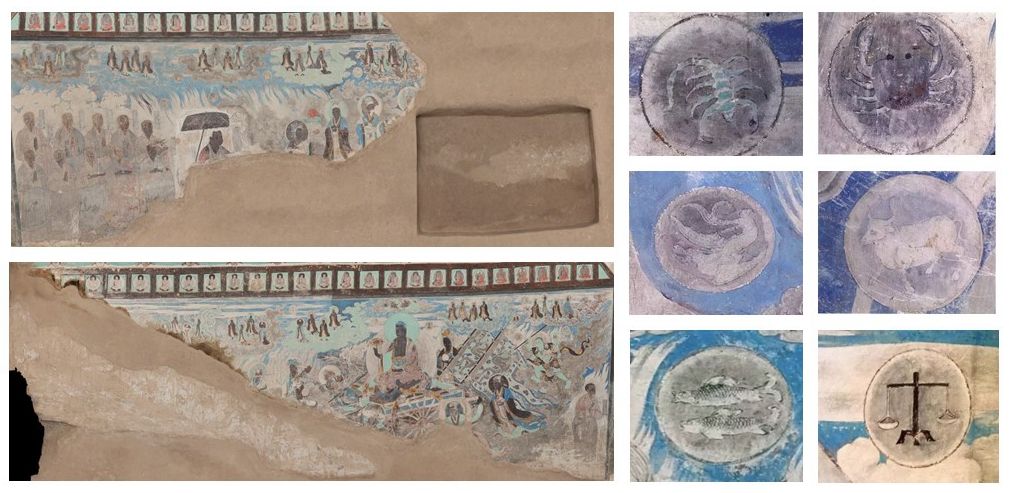

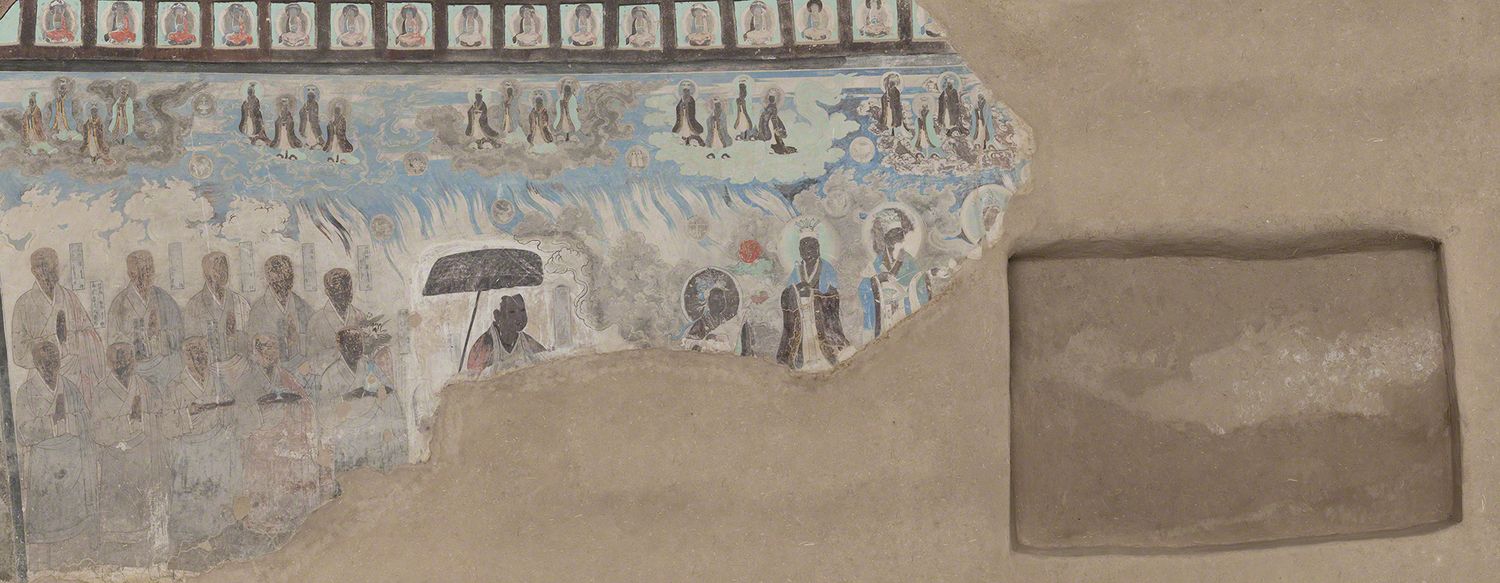

A particular Buddhist belief further spread the 12 astrological signs among the common people in ancient China: the worship of the Tejaprabhā Buddha, or the “Buddha of the Blazing Lights,” popularized in the seventh century, and later spread to other East Asian countries. The Buddha was believed to control planets and constellations and could dispel natural calamity. One example is in the Mogao Caves of Dunhuang, Gansu province, a mural dating around the 11th century that shows the Buddha surrounded by 12 astrological signs. While some of the figures have become unrecognizable due to the passage of time, those representing Scorpio, Cancer, Taurus, Capricorn, Pisces, and Libra remain clearly discernible.

There is also evidence that the 12 astrological signs entered people’s daily lives during this time. Capricorns are typically associated with a life of hardship in popular astrology today; surprisingly, renowned Northern Song dynasty (960 – 1279) scholar and poet Su Shi (苏轼) also subscribed to this belief. Su suffered many setbacks in officialdom despite his talent and upright character. In his essay collection A Compilation of Dongpo (《东坡志林》), he wrote: “I am destined to face hardships like a Capricorn, having encountered much slander through my life.”

Another example comes from Su’s contemporary, the 13th-century poet Yin Tinggao (尹廷高). In an elegy for his friend, he wrote: “A life of hardship like that of a Capricorn, leaving behind a desolate grave in Leiyang.”

Hundreds of years later, the belief remained: the 18th-century poet Cheng Jinfang (程晋芳) wrote a poem after surviving a boat wreck: “Don’t lament the difficult fate of Capricorn; when have the storms of the world ever been calm.”

Apart from assigning zodiac signs to individuals, ancient astronomers also matched cities and regions with zodiac signs. This unique practice in traditional Chinese astrology is called “divisions of the sky (分野).” Although traditional Chinese zodiacs were based on the motion of Jupiter and used to record a 12-year cycle, people nevertheless incorporated Western zodiac signs into the local system.

Chen Yuanliang (陈元靓) outlined some of these systems in his compiled Extensive Records of Matters (《事林广记》) in the 13th century. For example, Yangzhou, where Nanjing is located today, corresponded to Capricorn; Yan, modern-day Beijing, corresponded to Sagittarius; and Bingzhou, now Shanxi’s Taiyuan, corresponded to Pisces.

Based on this theory, a series of rather superstitious divination stories emerged. In the 14th-century historical novel The Vernacular Three Kingdoms (《三国志平话》), it is said that Zhuge Liang (诸葛亮), the famous strategist of the Shu state who existed approximately 1,500 years prior, invited the emperor Liu Shan (刘禅) to observe various nighttime celestial phenomena. When they witnessed a meteor shower in the Constellation Leo—which corresponded to Yizhou, located in modern-day Sichuan—Zhuge predicted that the area should prepare for trouble.

Much of the historical confusion around ancient astrological signs and constellations arises from the fact that it was not until the 19th century that many of the names were standardized. Finding the translations to be chaotic, Kang Youwei (康有为), a leader of the 1898 Hundred Days’ Reform movement, decided to unify them according to the Western tradition in his astronomy book Lectures on Heavens (《诸天讲》). For example, Gemini had been variously translated as “Yin-Yang (阴阳),” “Male and Female (男女),” and “Dual Birds (双鸟),” but Kang renamed it 双子, literally “twins,” which it remains today.

From then on, books introducing Western astronomy used Kang’s translations as a framework, making only some minor adjustments. Therefore, some of the alternative constellation names still used, such as 宝瓶 (Treasured Bottle; commonly translated as 水瓶, literally “water bottle”) for Aquarius and 人马座 (Person on Horse; commonly 射手座, or “archer”) for Sagittarius, are actually remnants from a long etymological process.

And so it came to be that the 12 Western zodiac signs seamlessly integrated into Chinese life, including daily conversation today. Despite the emergence of new icebreakers, like comparing MBTI personality types, it’s unlikely that “What’s your zodiac sign?” will disappear anytime soon. Though perhaps next time you can open with the more impressive, “Did you know the ancient Chinese also discussed signs?”