Once a major hub for clothes manufacturing, Guangzhou’s Kanglu district has in recent years been beset by difficulties, including Covid-19, competition fueled by the rise of e-commerce, and a protracted facelift

In Guangzhou’s “garment kingdom,” factory worker Xiao Xilin finds himself with more time on his hands than usual.

At around 10 a.m. on October 1, the 47-year-old garment worker arrived at the Lujiang Labor Market hoping to get hired, despite most factories being closed for the weeklong National Day holiday.

“When I was here a week or two ago, there were probably just 50 recruiters in the entire market,” says Xiao. This number is only about a fifth of its peak when the market first opened last year, according to Guangdong-based media outlet Southern Metropolis Daily. The job market is currently the worst Xiao’s ever seen: even on the rare occasions when a factory worker offers him a gig, the pay is a mere 60 to 70 percent of what it used to be—hardly worth the effort of showing up at the market and waiting.

Rise and fall of China’s “garment kingdom”

Adjacent to the Zhongda Textile Market in Guangzhou’s Haizhu district, the Kanglu area—comprising Kangle and Lujiang, two former villages swallowed by the urban sprawl—has been a major garment production hub in the Pearl River Delta since the 1990s. Known as China’s “garment kingdom,” this one-square-kilometer area is home to over 30,000 factories and workshops. At its peak a decade ago, the garment industry ecosystem in the area generated over 200 billion yuan in revenue.

Read more about lives of migrant workers in China:

- The Aging Migrant Workers Who Can’t Afford to Retire

- Why China’s Gen Z Migrant Workers Are Leaving the Assembly Line

- Scavenging for Door Plates: The Forgotten Stories of Urban Villagers

However, in October 2022, a severe Covid-19 outbreak triggered a lockdown lasting over 40 days, highlighting poor sanitation and safety concerns in these densely populated “urban villages.” Following the outbreak, local authorities enacted a 10-year urban renewal plan of Kanglu, marking the beginning of an extensive transformation.

Demolitions began at the end of 2022, initially focusing on illegal additions like rooftop workshops. By December 2023, full building demolitions had started as part of a phased plan to renovate Kanglu across 10 designated zones spanning 110 hectares.

Now, nearly two years into the project, progress has been slow yet steady. Approximately 329,000 square meters of illegal structures and 3.2 percent of the area earmarked to be renewed have been cleared so far, with dozens more buildings currently blocked off by barriers. Meanwhile, daily operations for many in Kangle continue, but changes are gradually emerging—and not all seem to be for the better. Workers and business owners report reduced hiring, lower wages, and declining business overall.

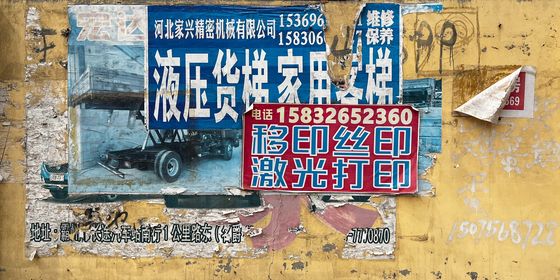

On October 11, four days after the end of the National Day break, TWOC visited the Lujiang Labor Market, a makeshift area in the village where factory owners and recruiters advertise available work by word of mouth or handpainted signs. There, many workers voiced frustrations about the slump in wages. A worker stormed off in dissatisfaction after inspecting a sample sleeve from a factory owner and inquiring about the piece rate. “One yuan for a pair of sleeves with complex stitching? It was 2.5 yuan just a few days ago!“ he fumed. The garment maker, who had worked in Kanglu for five to six years, told TWOC that rates per piece had plummeted from around 3 yuan in the past to barely 1 yuan now. “At this rate, no one would take the job,” he grumbled.

In another corner, a worker in his 40s was inspecting a sample tweed jacket held up by a factory owner, but walked away soon after. He told TWOC he used to earn 12 yuan per jacket stitched, but now the rate had dropped to just 8 yuan.

Unlike many other garment hubs in China, whose order turnover time might last from weeks to months, Kanglu has developed a unique “small batches, quick delivery” model. Factories in the area mostly make fast-fashion womenswear bound for Guangzhou’s large wholesale garment markets like Shahe and Thirteen Hongs. In Kanglu’s self-contained garment ecosystem, wholesale buyers would source fabric from the nearby Zhongda Textile Market, then place small orders with Kanglu’s garment factories, and re-upping according to demand. With materials, manufacturing, and sales and recruitment activities all concentrated in a single neighborhood, the local factories are adept at filling these orders within as little as 24 hours.

Fierce competition meant that in previous years, factory owners had to scramble to find workers to deliver orders on time, even raising their rates of pay to outbid rival producers. The high demand meant that garment workers in Kanglu were better paid than long-term contract workers at larger factories and those in neighboring manufacturing hubs like Foshan.

But now, those times of plenty seem to be fading fast.

Xiao, who moved to the area 14 years ago and has since lived off a steady stream of daily paid gigs in its clothes factories, notes that a skilled garment worker could previously make around 500 to 600 yuan for 15 hours of hard work a day on average; now, 300 to 400 yuan is more typical, unless they put in grueling hours. He attributes this downturn to the urban renewal that drove numerous factories out of Kanglu, seeing order volumes simultaneously drop. Gesturing toward a nearby and newly roofless building, Xiao estimates that demolished structures alone might account for one-sixth to one-seventh of Kanglu’s factory losses over the past two years. Yet, jobseekers continue to crowd into the neighborhood, further pushing wages down.

For experienced workers like Xiao, this wage disparity is a hard pill to swallow. According to him, it takes more than 10 years of toil to become a skilled worker in the industry, and no workers with that level of experience would think they only deserve 20 yuan per hour.

Declining business

Meanwhile, factory owners in Kanglu are also struggling as orders dwindle and clients become scarce.

When TWOC meets Li Yanfeng, who requested the use of a pseudonym, he is sitting on a stool on Lujiang’s Nanyue street, once a bustling recruitment area. Li is playing on his phone next to a chalkboard proclaiming “Clients wanted” and listing the types of women’s apparel his factory specializes in. He tells TWOC he has been waiting on the street like this for two months without landing a single deal. “Even in [previous] bad years, I’d still pick up some clients. It has never been this bad,” he says.

Li has spent 10 years in Kanglu, climbing his way up from a factory worker to the owner of a 300-square-meter manufacturing business. He recalls the early days when he could simply leave his sign out on the street without even showing up in person and still receive dozens of calls a day from eager wholesalers. “Back then, it was the clients who sought us out, not the other way around,” he says. In those peak years, Li’s factory could produce over a thousand garments per day; now, he is lucky to get orders for a few hundred, mostly from loyal clients. He often works a day, then waits nervously for several days for the next order to arrive.

Typically, September marks the start of the garment industry’s peak season as it prepares for fall and winter sales. But at least five factory owners in Kanglu that TWOC spoke to all reported almost no new clients this year.

Yu, a factory owner from the central Hubei province, describes frequently waiting from 11 a.m. to late afternoon on Nanyue street without meeting a single customer. He runs a 200-square-meter factory that once had around 30 workers, but now retains only about 10 regular employees due to the lack of business.

Many owners blame the downturn on the weak national economy and a sluggish apparel market. According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, apparel retail sales have slowed significantly since the third quarter of this year, dropping 1.6 and 0.4 percent year on year in August and September respectively. In an industry report released on October 17, Chen Dapeng, vice president of the China National Textile and Apparel Council, noted that although fall and winter sales have brought some seasonal uptick to the industry, market activity remains weaker overall than in previous years.

For Kanglu, the demolitions have potentially exacerbated the situation. Many clients have shifted orders to other urban villages in Guangzhou, such as Tuhua, where rent and labor costs are lower. “It’s natural for clients to follow the lower cost,” Li explains. “If more factories leave Kanglu, so will our clients.”

A transitioning landscape

According to some scholars and industry professionals, the recent redevelopment efforts have only accelerated the demise of Kanglu’s garment industry, which was already in a downturn. Sun Zhanqing, deputy director of the Urban Governance Institute at the Guangzhou Academy of Social Sciences, tells TWOC that after decades of growth, Kanglu has reached saturation. “Even without urban renewal, it had limited room for further industrial expansion,” he explains.

During China’s Reform and Opening-Up era, Guangdong’s garment manufacturing sector boomed, drawing over 300,000 workers from inland provinces such as Hubei. These workers opened and staffed Kanglu’s small family-run factories, and primarily handled bulk orders for Guangzhou’s wholesale markets. However, the rise of e-commerce decimated Guangzhou’s traditional wholesale markets, weakening Kanglu’s position as a manufacturing hub.

Factory owners in Kanglu describe to TWOC how the garment industry is no longer as profitable and is far more competitive than it was a decade ago, when they could hear colleagues making millions annually. Some factories have begun handling e-commerce orders, but the transition has been difficult. Deng, a factory owner from Hubei, recounts producing women’s summer jumpsuits for an online retailer; they only offered 15 yuan per piece despite a production cost of 13 yuan.

Meanwhile, inland provinces and cities have started attracting garment manufacturers away from the coast, leading to competition from new garment production hubs across the country. For instance, Tianmen, a city in Hubei, has grown into a major apparel e-commerce base in recent years, processing over 185 million clothing-related e-commerce parcels this year—40 times that of 2019.

Yuan, a factory owner from Qianjiang, also in Hubei, relocated operations of his 300-square-meter factory in Kanglu to his hometown this year. Despite Kanglu’s central location, Yuan explains that the limited space available in Kanglu constrained his aspirations. In Qianjiang, he has now expanded his factory to over 2,000 square meters, significantly boosting production capacity and output.

Meanwhile, the Guangzhou municipal government is seeking to revamp Kanglu and oversee an “industrial upgrade” of the area, transforming it into a high-end fashion industrial park. To support this transition, the authority has planned to preserve 90 to 100 “key garment enterprises” in the area while encouraging those not selected to relocate to nearby industrial zones like Qingyuan, 80 kilometers away from central Guangzhou.

But Kanglu’s intricate supply chain, integrated with the wholesale and textile markets, complicates the upgrade. Sun notes that relocating these small but interconnected factories could erode Kanglu’s supply chain and competitive advantage. As part of the redevelopment project, he advocates for more high-rise buildings to provide production space for these smaller businesses and workshops, keeping them in the area and empowering them via new production models, such as using digital platforms to integrate into manufacturing cooperatives.

For those workers and small factory owners who have decided to stay, the future remains uncertain. Concerned that they face significant losses if business doesn’t pick up, they mostly focus on living day to day, taking business as it comes. “If I can just cover rent this year, I’ll consider it a success,” Li admits.

Xiao is still looking for a job worth his while, and has fallen back on his rent by several months. He’s unsure what his future holds for now, but if things continue like this, he does consider leaving. “As long as I’ve saved enough money for the trip,” he says.

Photography by Shihuan Chen

In Southern China’s Once-Thriving “Garment Kingdom,” Business Fades Amid Urban Renewal is a story from our issue, “New Game.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.