With the recent release of “Black Myth: Wukong,” Canadian writer and translator Dylan Levi King reflects on the popularization of a Chinese literature classic

When it arrived on gaming platforms at the end of last month, Black Myth: Wukong became, in addition to a runaway commercial success, a vehicle to transmit to millions around the world one of the jewels of Chinese folklore and literature: Journey to the West (《西游记》), Wu Cheng’en’s (吴承恩) 16th-century novel of pilgrimage woven out of collective legend and individual imagination.

Even though he drafts an extensive array of fantastic creatures, gods, and demigods, Wu Cheng’en had a retelling of the real-life adventures of Xuanzang (玄奘) as the core of his narrative. In search of Buddhist scriptures, the Tang dynasty (618 – 907) monk took a clandestine voyage down the Silk Road to as far as the Kanchipuram in what is now the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, and eventually returned to the Tang capital Chang’an to translate the sutras he secured.

Treacherous journeys of thousands of miles are no longer required to spread culture. But meaningful exchanges and mutual learning seem more difficult than ever to accomplish.

Black Myth seems unmistakably a labor of love by people who took it as their goal to celebrate and convey Chinese folklore and culture. In the opening sequence, Sun Wukong (孙悟空), better known as the Monkey King, faces down the Celestial Court, with the crowns of the gods piercing the clouds—a conception of the rulers of the universe pulled from folk religion, as well as Wu Cheng’en’s satirical portrait of petty gods. The attention to detail throughout is remarkable and meaningful, with real-life locations carefully recreated in the game as they might have looked centuries before, and credible references made in the gorgeous animated cutscenes to Wu Cheng’en’s text.

Playing for a few hours as the Destined One (a descendant of the Monkey King, out to find the relics in which his ancestor is fragmentarily embodied after being beaten by the Celestial Court)—or rather, peering over the shoulder of a more competent, committed gaming friend—I began to think about how Journey to the West came into my own world.

Read more about classic Chinese literature:

Like many others in the Anglosphere, it was through Arthur Waley’s 1942 abridged translation called, simply, Monkey.

I returned home from my gaming session and flipped open my worn copy of Monkey, thinking about the genealogical possibilities in connecting Waley’s text to Black Myth, and found myself savoring the opening lines anew:

“There was a rock that since the creation of the world had been worked upon by the pure essences of Heaven and the fine savours of Earth, the vigour of sunshine and the grace of moonlight, till at last it became magically pregnant and one day split open, giving birth to a stone egg, about as big as a playing ball. Fructified by the wind it developed into a stone monkey, complete with every organ and limb.”

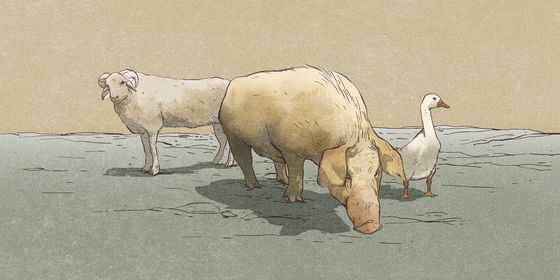

It is thanks to Waley’s popularization that the plot of the novel does not need to be recounted beyond the briefest sketch: A monk named Tripitaka is sent on a pilgrimage to India to retrieve Buddhist scriptures, accompanied, at the appointment of the Bodhisattva Guanyin, by the Stone Monkey, as well as the licentious demigod Pigsy, the ogre-like Sandy, and a dragon prince that the Bodhisattva has transformed into a horse.

Waley’s version endures. Other translators had offered their own attempts at Journey to the West before, and many more have since. Timothy Richard’s interpretation, published nearly 30 years before Waley’s and lately re-evaluated and revised, is notable among predecessors: Anthony C. Yu’s multi-volume translation, appearing another few decades after Waley’s, is widely considered the most complete in English. W.J.F. Jenner’s translation for Foreign Languages Press might be the most widely read behind Waley’s, and Julia Lovell has the most recent update. Where Waley triumphed was by doing something special to the text, treating it as the raw material to make his art.

Under the influence of modernist poets such as Ezra Pound, who sought inspiration in Chinese poetry, Waley broke with a generation of Sinologists, including Herbert Giles, who prized philological fidelity in translation. Rather than producing the sort of stiff texts that fellow Sinologists might use to crib the original, his goal was to transmit to a general readership the exquisite beauty, vitality, and musicality of the original texts.

When Waley embarked on Monkey, he was reaching the peak of a long career, having already tackled Tang poetry, The Analects of Confucius (1938), and Japanese literature, The Tale of Genji (1925 – 1933). Monkey is the most accessible of his translations, befitting his view of Journey to the West not as a religious allegory, as other scholars held, but as a gleeful picaresque. He streamlined the text, slicing away everything he deemed superfluous—poetic introductions to chapters, for example, and repetitive plots, some marginal characters—and sanding down the ornate embellishments. The religious allegory that other translators and scholars saw as central to Journey to the West was blunted.

As David Lattimore wrote in a reevaluation of Waley after the publication of Anthony C. Yu’s translation, “Waley may have caught the color of Monkey’s mind, but in his 300 pages, rendering less than a third of the complete work, he made no attempt to capture the scale of the original.” As Wu Cheng’en wove together folklore and fact into a stout, sprawling novel for his time, Waley composed an adventure story from the episodes in the original.

The developers at Game Science who made Black Myth are, in essence, doing the same: They have emptied into a video game what has been passed on through legends and histories (and television programs, too, since the popularity of the 1986 China Central Television version cannot be overstated, as well as films like Stephen Chow’s Journey to the West: Conquering the Demons in 2013).

For the generations that encountered Journey to the West through Waley’s translation, it was a portal into times and places, both realistic and fantastic, that they had never experienced. It was a vicious, funny story. And, for some, like me, it was an embarkation point, the start of a deeper dive into the literature of Wu Cheng’en’s era, into The Plum in the Golden Vase (《金瓶梅》) and Investiture of the Gods (《封神演义》), onto centuries of commentary and reaction and riffs, and outward into other sprawling pre-modern novels. It was a way to understand the landscapes I saw while traveling in China’s far west, and a way to decipher the deities on wall calendars and in shrines. It was a topic to bond with strangers over.

Perhaps Black Myth could serve a similar purpose, albeit for a post-literate age.