Students of sports majors face the tough reality of limited job opportunities after graduation

August 3, 2024 was a historic day at the Stade Roland Garros in Paris. China’s Zheng Qinwen claimed the nation’s first tennis singles gold medal—the first won by any Asian athlete—at the Olympics. Chinese netizens lost no time asking: How does one go about forging a tennis queen?

Zheng herself gave the answer in her post-victory interview: “My dad sold our house to fund my tennis lessons.” The internet speculates that Zheng’s family may have spent a whopping 20 million yuan in her meteoric career, maybe more. Zheng may have technically made history with her own tenacity and hard work, but it’s also a fact that her family gambled all on her success—probably to the envy of millions of other Chinese parents who sink astonishing amounts of time, energy, and funds into the long game of raising successful kids, but have to settle for far more modest prospects. This is especially true for parents who want to raise young athletes.

Athletically gifted kids who decide to formally pursue sports require a great deal of support from their families. Often, the whole extended family rallies around their sports wunderkind following the so-called “1+6” model, where the parents and both sets of grandparents take turns looking after the kid and handling pick-ups and drop-offs from school to training—rain or shine. Families with kids in the arts have a similar setup, except sports tend to be easier on the wallet for the average family.

Read more on education in China:

- The Boom of College Admissions Counseling in China

- Bottom of the Class: The Woes of China’s Liberal Arts Students

- No Time to Teach: Why Many Chinese Teachers Are Leaving the Profession

Eventually, they hope their kids will get into college based on their “athletic talent”—perhaps boosting less-than-stellar academic scores—and become “sports majors (体育生)” or “sports talent majors (体育特长生).” These students typically study related subjects like sports theory, physiology, or sports psychology, and play on college teams. Unlike the prodigies recruited into national or provincial sports teams, most sports majors are not preparing for a competitive athletic career, but are meant to be the “reserve forces”: working in supporting roles, raising the nation’s general athletic level and interest, and diversifying the college recruitment process.

Even then, most of these kids can’t and won’t enter even a sports-adjacent career. Zheng is an exception: For ordinary sports kids and their families, just an ordinary future is enough of a gamble.

The best athlete at the bank

“Have you heard? That dude broke the record again!”

Li Yu is the talk of the office again, having broken the long jump record at the annual sports meet held by the bank where he has worked for the past two and a half years. Sports meets are a common team-building initiative for state-owned enterprises, meaning to foster unity and team spirit among the staff. “He broke the 400-meter dash record last year too. They always put him on the team because he majored in sports,” senior employees would proudly share with new recruits at the office.

In college, Li never could have imagined working in a bank, nor hearing the words “Account Manager” after his name. He thought he’d sail into a job teaching in a public school like his peers, but after countless job interviews, no schools ever offered him a job. Desperate, Li took his job search online, and eventually, he came upon a chance: an ad from a bank calling for graduates with sports expertise.

If you look at the hiring ads from state-owned banks, every year there are one or two teller or account manager positions asking the applicant to have some expertise in sports or the arts. There are many inter-bank and intra-bank competitions, and each department wants to field a few players who won’t embarrass the company. It is not just banks; state-owned companies with a lot of extracurricular activities also love sports graduates.

However, not everything has been smooth sailing for Li as a bank employee. The second time he stood on the podium at the company sports meet, the general manager handed him his medal and sang the praises of the bank branch where he worked. He said to Li, “I remember you from last year. You were also on the podium.” His bosses didn’t remember him for his professional skills—just his ability to run fast and jump far.

At the time, Li’s mind was still fresh from a scolding by his direct supervisor on how he hadn’t brought in enough new customers nor met his KPI. Now, seeing that the bigwigs were praising Li, his supervisor started patting him on the shoulder and telling him how proud he was. Li didn’t know what to make of that.

The truth is, as a sports major, banking does not come easy to Li. He has had to sweat more than his colleagues to learn every ounce of financial knowledge from scratch. Overcoming his social awkwardness wasn’t easy, either, making customer service an ordeal for both parties. In his supervisors’ eyes, Li couldn’t compete with his colleagues, and they frequently brought him in for a telling-off.

These days, Li is thankful he pursued sports. It gave this ordinary young man a stepping stone to a career and, occasionally, a chance to shine.

State-owned havens for sports majors

As the father of a young child and a sports major in college, Liu Ting felt lucky when he finally scored a position teaching physical education at the elementary school in his hometown. It wouldn’t make him rich, but he could live close to home, and the work wasn’t hard, not even with the extra responsibility of leading sports clubs in training and competitions. He could hop on his scooter and get to work in 10 minutes, while dropping his son off at the kindergarten next door. He could watch sports in the evenings and take his family on vacations.

Liu is satisfied with his decision to return home and teach—it’s paradise compared to the “996” jobs that city folks slaved in the news. Still, this decision came much later in Liu’s life compared to his classmates. Years earlier, he’d taken the path of “sports recruitment” to gain admittance into university: taking the national college entrance exam (gaokao) as well as a provincial sports examination for students with sports talent. From day one, half of these people knew that they were destined for a career in schools and government offices—not in the Olympic stadiums.

Liu chuckles with his own joke that out of every 10 graduates from a sports program, you are sure to get 5 teachers and 4 civil servants. “The remaining one? They’re studying for the qualifying exam!” He’s only half-kidding: Among China’s sports majors, about an equal number go on to become high-ranking officials as there are world champions. Liu’s two best friends from college are now police officers and PE teachers back home. The boys who kicked balls, drank, and stayed up late together have now all settled down. They all report to someone else at work, play guandan poker game or basketball and badminton in their downtime, and discuss politics online. Their WeChat profile pictures have changed from Cristiano Ronaldo to their kids or a generic photo of nature.

But 10 years ago, they also had dreams of “making it,” and stood at the crossroads between adventure and safety. Liu coached swimming in college, and after, he and a few of his school buddies took over the lease of a swimming pool with the intention to set up a coaching business. It was summer, and his skin peeled under the hot sun. In 40-degree weather, he ran around getting business permits and disinfecting the pool. It was hard but satisfying work, and he earned his first pot of gold in life.

Many students from his school had harbored entrepreneurial dreams. Most of them had coached part-time during school vacations, so setting up their own coaching business seemed like the natural next step. But stories of businesses that fail and partnerships that break up are just as common. Liu’s own venture lasted two years, but he doesn’t regret his life now, though it’s much less lucrative than his business would have been, had it succeeded. “Between CEO Liu and Teacher Liu, I like the sound of the latter,” he says.

Shedding the sports label

If you ask Lu Xueting how much influence her sports major had on her life after graduating college, she’d answer, “about 1 percent, or even less.”

As the marketing director of a car dealership, Lu’s day is filled with running marketing events, setting up venues, live broadcasts, and attending trainings. It’s a busy life, but the rewards come in the form of great feedback from her superiors, a six-figure balance in her bank account, and the privilege of taking her parents on frequent vacations.

Aside from her height of 172 centimeters, no one would now associate Lu with being a sports major. She couldn’t qualify for a public university, and, knowing her family couldn’t afford tuition fees for a private college, she opted for a less prestigious vocational college.

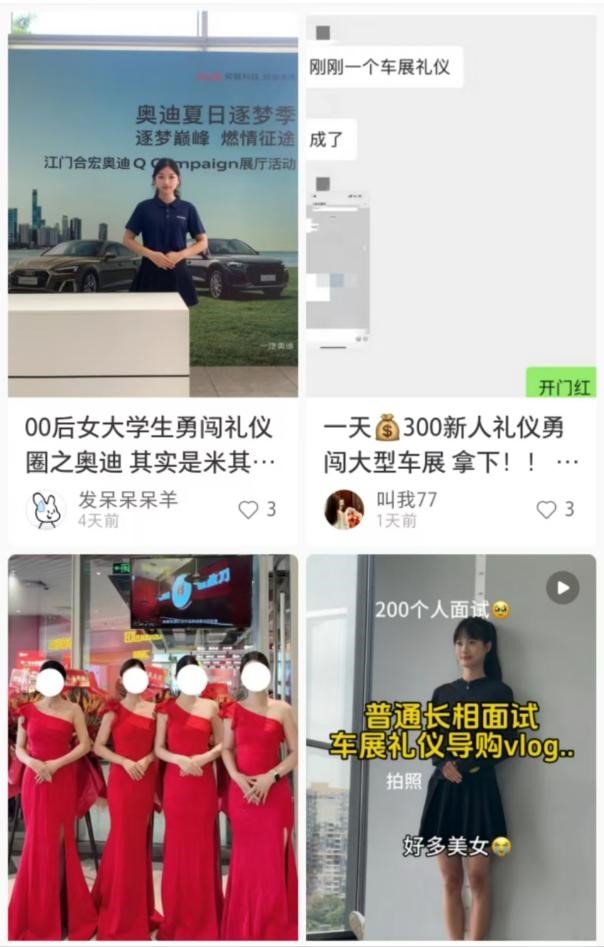

However, graduates from these schools aren’t well-positioned for civil service jobs, which prefer applicants with an undergraduate degree. Many of her classmates continued their studies after graduation, but others went into various occupations—from coaching to e-commerce, sales, and new media. All of Lu’s roommates chose careers away from sports except for one. The girl who stayed in sports worked as a personal trainer for two years before quitting to get married and opening her own private gym. She got a Senior Personal Trainer certification from the Chinese Bodybuilding Association and certificates in nutrition and female hormonal management—her college degree is the least dazzling line in her resume.

Lu, too, has been able to channel parts of her sports major into her current career. In college, due to her height, she was often recruited to be an usher or model at industry events, which was how she got acquainted with car companies. Today, people often tease her for her multitasking and time-management abilities: an event in Guangzhou one day, eating roast duck in Beijing the next. “If sports kids like us are known for one thing, it’s having lots of energy,” she quips.

But that high-energy life is about to wind down. This June, Lu got married, and she wants to start a family. Unemployment is no longer an option, but she worries that late-night shifts could impact her fertility.

Would her life have been different had she gone to a better college and become a teacher or civil servant? Lu is starting to have second thoughts. At least, she thinks, she wouldn’t have to hide her maternity plans from her supervisors in a state-run company, worrying that they’ll try to squeeze her out of her job.

Freedom to be ordinary

Every year, sports as a college major becomes a topic of heated online debate—particularly during gaokao season, or in response to major events like Zheng Qinwen’s Olympic laurels. Plenty of people insist that sports majors enjoy a shortcut in life: still getting into college with less-impressive gaokao scores, and settling into a cushy civil service or teaching career after college.

But that couldn’t be farther from the truth. Sports kids are like an army of 10,000 chariots trying to cross a single log bridge into college, and their choices after graduation are even more limited. They are all competing for the same teacher and civil servant positions, while private gyms prefer to hire more experienced coaches over fresh graduates. Their three or four years in college may be the closest in their lives they get to playing sports full-time.

And after the whistle blows? They morph back into ordinary adults, exchanging their bodies, brains, and skills for a paycheck. Perhaps it’s only when they stay up late to cheer on the Olympians that their hearts become young again.

But at least, sports has given them that option.

All names in this article are pseudonyms