Based on the true story of Su Min, China’s latest box office hit reflects on the quiet endurance of generations of women and questions whether leaving is the end—or just the first step toward reclaiming independence

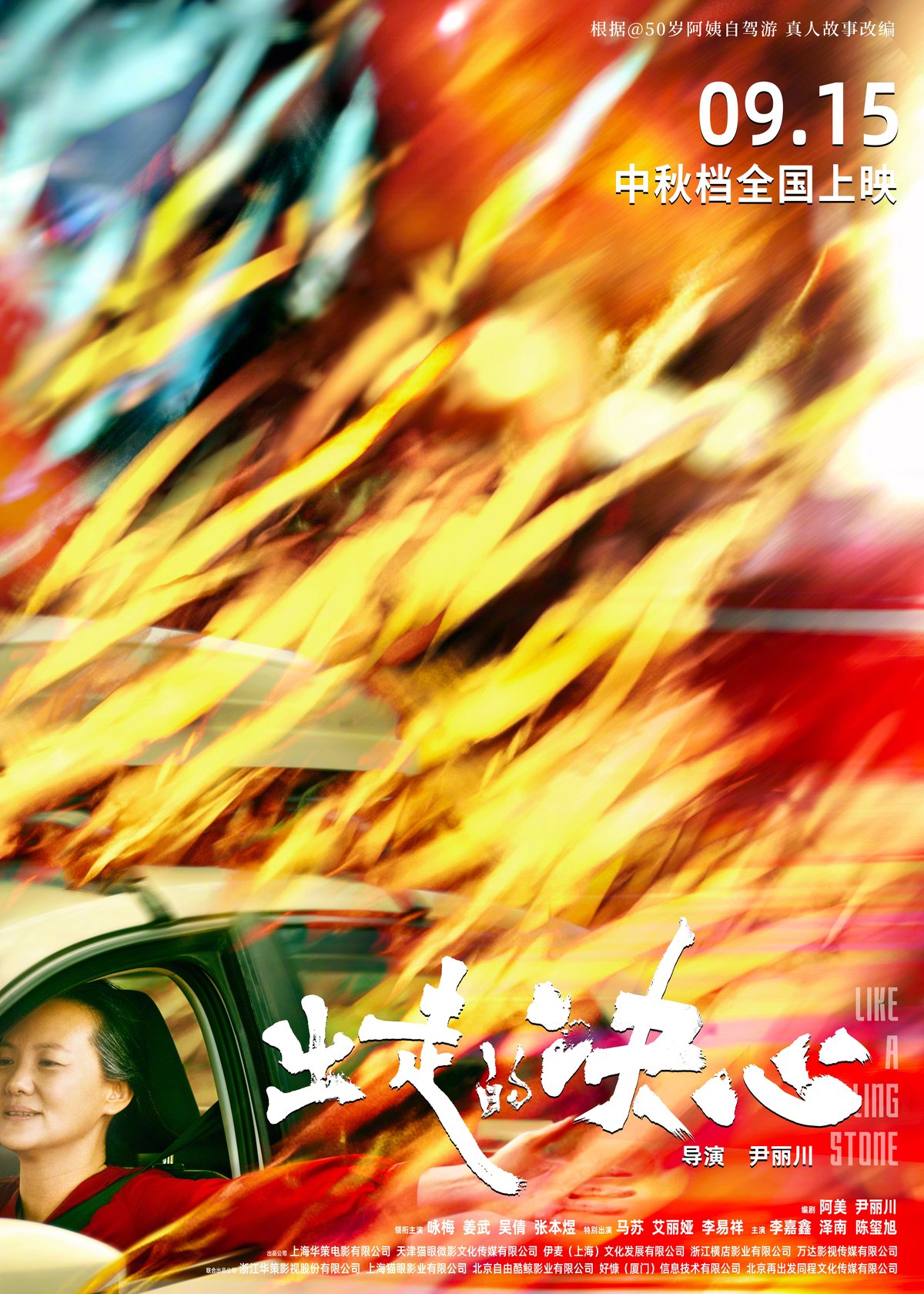

The Bob Dylan-inspired English title of Yin Lichuan’s Like a Rolling Stone—and the well-advertised fact that it’s based on the true story of Su Min, a woman who went on a solo drive across China to escape an abusive marriage at the age of 56—gives the impression that it’s a road trip movie.

Instead, Su’s fictional avatar, Li Hong, never hits the road until the last 10 minutes of the 106-minute film. The other 90 minutes take place mostly in the cramped apartment and dimly lit streets where Li has slaved for 30 years for an entitled husband, a needy daughter, and eventually grandchildren. It is an almost overly accurate illustration of Simone de Beauvoir’s well-quoted saying that “one is not born, but rather becomes a woman.”

The film’s lopsided pacing may be frustrating, but it’s also painfully realistic: In the opening scenes, we already learn that Li Hong (Yong Mei) has long wished to travel to catch up with old high school friends in Chengdu, Sichuan province, only to watch her gently shelve this suggestion again and again in the next hour-and-half due to the next crisis needing her attention at home, and later Covid-19. The final time she puts off the trip, after already learning to drive and buying a car and a tent, there were audible groans in the audience at a special screening of the film on September 19 in Beijing. But judging from comments from the screening audiences and commenters on China’s major film review platform Douban, who saw their own mothers and grandmothers reflected in Li, maybe the film simply drew out the reaction we should have had all along to the generations of Chinese women who’ve been taught to put aside their own needs, feelings, and desires to serve the family without complaint.

The film’s Chinese title Chuzou de Juexin (《出走的决心》), which translates to “The Resolve to Leave,” perhaps better captures the director’s intention. As Yin told the audience in a panel discussion after the screening in Beijing, it’s not the “leaving” part but “the resolve” that the film was meant to highlight. “Leaving is not necessarily a physical act, but first requires becoming independent in spirit,” she said.

Read more about feminism on screens:

- Nü Perspectives: Striving for Better Female Characters on Chinese Screens

- The Rise of Female Perspectives in China’s Movie Industry

- Why 1980s Hong Kong Novels Still Dominate Chinese Screens

Li Ying, a lawyer specializing in women and children’s rights, agreed. “The biggest barrier to women is our [society’s] collective consciousness, the contributions from women we take for granted,” she said in the same panel discussion. “Women have been socialized to ‘put up’ with things.”

The things Li Hong puts up with in the film are rarely dramatic, but are rather a thousand small, repetitive cuts that transform her from an ambitious college-bound student to the family drudge who acquiesces—without being explicitly asked—to stay home to help her daughter with a difficult pregnancy and hard times at work. While Su Min, in real life, has said that her (now ex-) husband drank and assaulted her, the film’s decision to remove these traits from Li Hong’s husband Sun Dayong—who is verbally and financially abusive, but has “benign” hobbies like ping pong and seems rather fond of his daughter—has been controversial.

Amid speculations of censorship, Yin claimed in interviews that softening Sun Dayong’s abuse makes the film more “widely relatable.” The problem isn’t just a few bad apples, but a systemic injustice, the film seems to argue; Su Min would feel similarly trapped had she married a (marginally) less monstrous man like Sun.

The subplot of Li Hong’s daughter Xiaoxue makes a similar point. Xiaoxue has a career and is married to Xiaoyang, a sympathetic millennial husband who compliments his wife, never loses his temper, and supports her decision to buy her mother a car. Yet Xiaoxue eventually loses her job because it’s she, and not Xiaoyang, who keeps taking time off to care for their twin sons, and he seems baffled by her outrage.

The complexity of Xiaoxue and Xiaoyang’s characters also shows that the systemic conditioning of women is not resolved with a simple change of generation. Xiaoxue, who has up to that point always defended Li Hong to her father and supported her desire to travel, suddenly accuses her mother of selfishness for wanting to leave just when she has just started a new job and needs her mother to watch the kids. Two generations of women in a patriarchy, it seems, must always fight each other for the single allotment of independence they’re allowed.

In Xiaoxue’s final appearance, she is sitting in the same drab kitchen that confined Li Hong for most of the film, having seemingly sacrificed her own freedom in exchange for her mother’s. Meanwhile, Li Hong’s scenes are a lushly colored montage of the road set to upbeat music, which then transitions into a reel of real-life adventures from Su’s social media. This suddenly optimistic ending feels rather emotionally unsatisfying, if not cheesy—how did Li achieve all those things she is shown to do, like learning to change a tire or meeting new friends? And what happens at home? It also recalls Lu Xun’s well-known 1923 speech “What Happens After Nora Leaves Home?” in which the renowned writer concludes that Nora, the protagonist of Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, will either “fall” (into prostitution) or come home after walking out at the end of the play. “Dreams are nice to have; otherwise, it’s necessary to have money,” Lu Xun said.

But then, Su’s own videos of her road trip were just as dazzlingly optimistic, and that was her appeal all along: a woman in middle age who suddenly realized she didn’t have to follow someone else’s script and could go wherever she liked. Perhaps the film’s answer to Lu Xun’s question is that it doesn’t matter what happens after Nora leaves. Even the decision to leave is a victory in itself.

Like a Rolling Stone: A Stirring Meditation on Womanhood and Defiance is a story from our issue, “New Game.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.