Learn these commonly used “chengyu” inspired by the superpowers of the Monkey King

The recently released Black Myth: Wukong has taken the gaming world by storm. Besides gaining plaudits for its graphics and addictive gameplay (and immense profits), the game has generated new interest in the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West.

The authorship of the novel is attributed to Wu Cheng’en (吴承恩), who is believed to have written it in the 16th century based on older legends and history. The novel follows the adventures of a Buddhist monk based on Xuanzang, who takes his disciples, including Sun Wukong the “Monkey King,” on a journey to India to find sutras. A cultural touchstone in China for centuries, Journey to the West has not only been been adapted numerous times into films, TV shows, and stage productions, but also gave rise to a number of common idioms and sayings, most of them celebrating the cleverness and bravery of the eponymous Wukong.

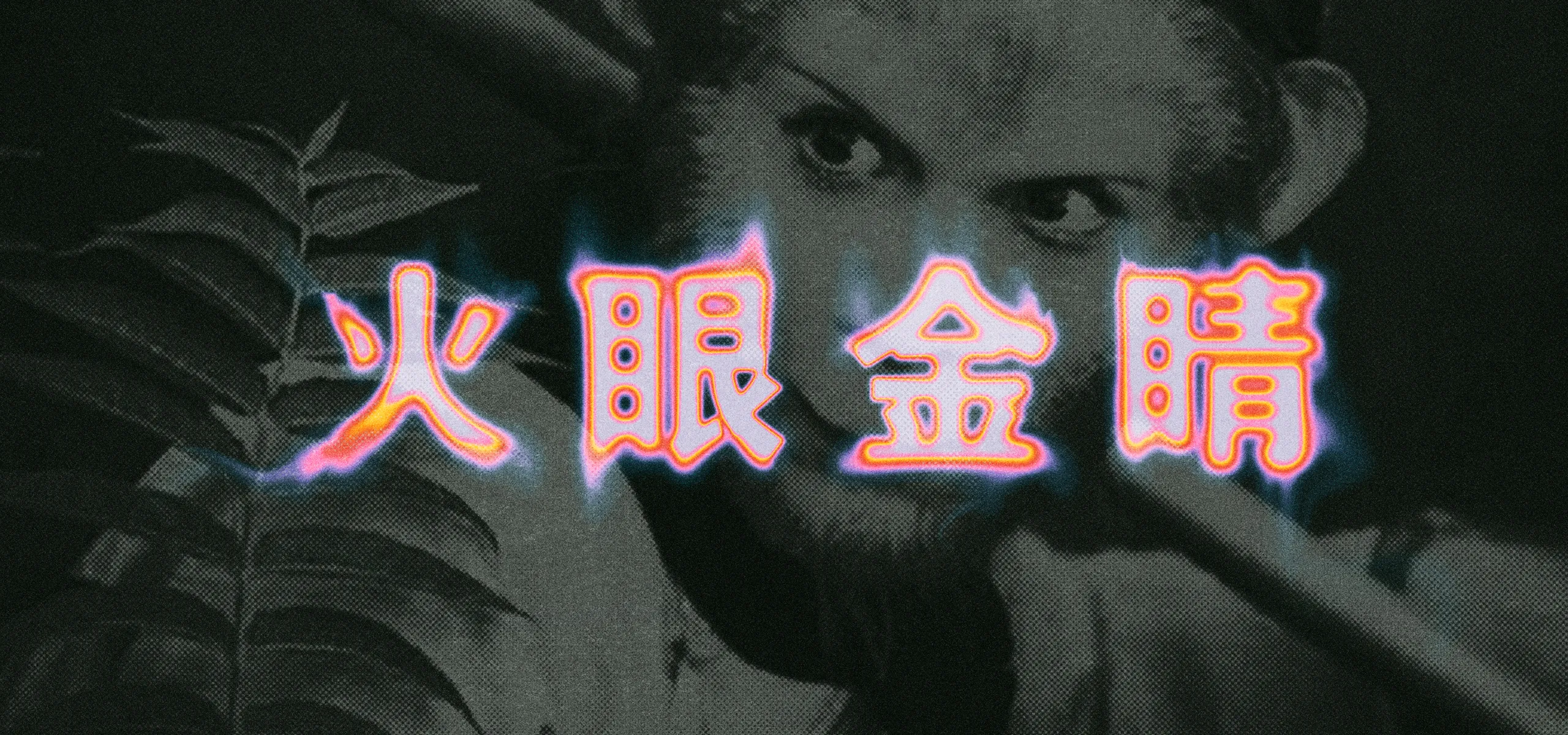

Eyes of fire and gold 火眼金睛

The opening chapters of the novel are dedicated to explaining the backstory of Sun Wukong, a monkey born from a stone. After becoming a student of the hermit Puti Zushi, Wukong acquires the ability to ride clouds, among many other superpowers. In one episode, after causing a riot in the Heavenly Court, he is condemned to be locked up in a furnace as punishment. He survives by escaping to a compartment where the fire cannot reach. However, the smoke left him with a permanent eye condition called “Fiery Eye.”

Learn more about Chinese idiom:

- How to Talk Fake News in 4 Characters

- How to Condemn a Hypocrite in 4 Characters

- How to Complain About Your Boss in 4 Characters

Oddly enough, instead of hindering his vision, Wukong’s fiery eyes allow him to see things hidden from ordinary humans, such as monsters who shapeshift or become invisible.

Nowadays, this idiom generally refers to someone’s ability to detect crime, wrongdoing, or deception:

His lies seemed flawless, but she still saw through them with her “eyes of fire and gold.”

他的谎言似乎说得天衣无缝,可还是被她的一双火眼金睛给识破了。

To have immense magical power 神通广大

The Chinese term shentong comes from the Sanskrit word abhijñā, which refers to a set of psychic powers acquired through Buddhist training. These include unhindered bodily action, divine vision, divine hearing, awareness of the minds of others, knowledge of past lives, and purification, collectively known as the “Six Psychic Powers.”

Wukong is the ultimate master of these powers in Chinese mythology: a leap with his jindouyun (筋斗云), a magical cloud he rides as a means of transport, sends him more than 100,000 li away. A whip of his jingubang (金箍棒) staff sends shivers down the spine of any evil spirit. Metaphorically, this phrase describes a highly capable person whose talents seem larger than life:

It’s like this person has immense magical power; she can accomplish things that others can’t.

这个人真是神通广大,别人办不到的事,她都有办法完成。

Transform with a shake of the body 摇身一变

“Transforming with a shaking the body” implies a kind of shapeshifting that doesn’t take much effort. The saying originated in the second chapter of the Wu Cheng’en novel, where it is mentioned that “Wukong, chanting a spell and rocking his body, transformed himself into a pine tree.”

The Monkey King is a master of illusion, and learns the magic incantation of qishierbian (七十二变), or “Seventy-Two Changes,” from Puti Zushi. In the novel, he transforms into a sparrow, a temple to the earth god, a wandering Daoist monk, and more, according to the needs of the plot.

Today, the phrase is often used metaphorically to convey a drastic change of status or situation:

With strong support from all sectors of society, this historic prison has been transformed into a luxury hotel.

在社会各界的鼎力支持下,这座历史悠久的监狱竟然摇身一变,成为了豪华酒店。

Three heads and six arms 三头六臂

In Buddhist sutras, some deities are said to have three heads and six arms. One famous example is that of Nezha, a god that is said to have “three heads and six arms holding up the sky” in The Jingde Record of the Transmission of the Lamp (《景德传灯录》), a Buddhist record composed in 1004.

In the fourth chapter of the novel, which recounts the Monkey King’s rebellion against the Heavenly Court, Wukong is assigned by the Heavenly Court to the stables. Feeling deceived by the low rank and lack of status, he returns to Huaguo Mountain and takes the title of Qitian Dasheng (Great Sage Equal to Heaven). Later, the Jade Emperor appoints a young fire deity Nezha to lead an expedition to catch Wukong and bring him back to Heaven.

This results in a famous combat scene between Nezha and Wukong, where the Monkey King transforms into the same form as Nezha and holds three jingubang canes in his hand, showing his unparalleled strength and agility.

In modern usage, this chengyu is used to describe people who have exceptional skills in managing complex situations or who are adept at multitasking:

Without three heads and six arms, how could he complete so many difficult tasks in such a short time?

要没有三头六臂,他怎么能在短时间内完成这么多艰巨的任务?

To have one’s true form exposed 原形毕露

One of the most memorable scenes from Journey to the West is the battle between Wukong and Baigujing, or the White Skeleton Demon. In the 27th chapter of the story (or the 20th trial of the 81 trials that Wukong encounters), Baigujing disguises herself as a village girl and offers Wukong’s master food in an attempt to gain his trust, before killing him and eating his flesh to achieve immortality. Wukong, with his fiery eyes, immediately sees through the monster’s traps and drives her away. But his master, the monk Tangseng, is fooled by the disguise and condemns Wukong for killing innocent bystanders.

Later, the demon returns as the old mother of the village girl, searching the mountain for her daughter. Wukong kills her again with his jingubang.

The third time, Baigujing comes disguised as an old man looking for his wife and daughter. Calling on local deities as witnesses, Wukong finally destroys the demon, leaving only a pile of white skeletal bones with the name “White Bone Lady” engraved on the spine. The popular idiom “to have one’s true form exposed” comes from this scene.

In modern days, when a secretly selfish or evil person shows their true colors, we can say:

We have always regarded him as a friend, but in crucial moments, for the sake of profit, he ultimately revealed his true colors.

我们一直以来把他看作朋友,但在紧要关头为了利益,他最终还是原型毕露了。