Why do Chinese speakers use QWERTY keyboards on their computers?

On a typical afternoon in the early 2000s, I would enter the computer room in my elementary school and start typing frantically using Kingsoft TypeEasy. The software, designed to improve typing skills through various exercises and games, was one of the most popular pastimes among my classmates and me in those days.

We were so fixated that we held unofficial competitions during class, often neglecting the actual lesson at hand to compete to see who could type the fastest. Even during the summer holidays, before my dad got me my own computer, I would spend days practicing touch typing at my cousin’s house.

I’m still proud of the speed at which I can type Chinese without looking at the keyboard. Like most people on the Chinese mainland, I type with a pinyin input method editor (IME), a computer program that allows users to generate Chinese characters not featured on a QWERTY keyboard.

But pinyin, the system that transcribes Mandarin Chinese into Roman letters, isn’t the only way Chinese can be typed out. Inspired by Thomas S. Mullaney’s new book The Chinese Computer, which traces the history and development of Chinese language computing technology, including the invention of IMEs just like one I learned on, I began digging into generational and geographical differences between Chinese-speaking people relating to typing our language.

Battle of the IMEs

While Chinese characters may look like drawings to non-speakers, Chinese keyboards today are nearly identical to their English-language QWERTY counterparts, and Chinese can be typed on any modern digital device and keyboard, including T9 on mobile phones. Advances in computer prediction and suggestions have made writing Chinese on digital devices much faster than back when one had to type out every component or sound of a character.

As Mullaney writes in his book, Chinese was often considered one of the slowest writing systems in modern information technology. However, “autocompletion was first invented in the arena of Chinese computing.” More broadly, this mode of digital Chinese writing has come to dominate non-Latin computing worldwide, Mullaney notes. “It was China and the non-Western world that saved that Western-designed computer,” he writes in the conclusion of the book, adding that without features like IMEs, autocompletion, and predictive text, “No Western-built computer could have achieved a meaningful presence in the world beyond the Americas and Europe.”

Learn more about China’s early computer culture:

- Tracing the Early Days of the Chinese Netizen

- The Rise and Fall of China’s OG Social Media Platforms

- Remembering the Glory Days of China’s Internet Cafes

While there were efforts in the 1960s and 1970s to design Chinese-friendly keyboards, QWERTY inputs were already dominating the global computing industry, and demand for devices used specifically for typing Chinese, comparatively expensive at the time, was low. After China’s economy opened up in the 1980s and ‘90s, a wave of mass-manufactured, QWERTY-based personal computers flooded the Chinese market, further cementing the need for a simple Chinese input method for typing.

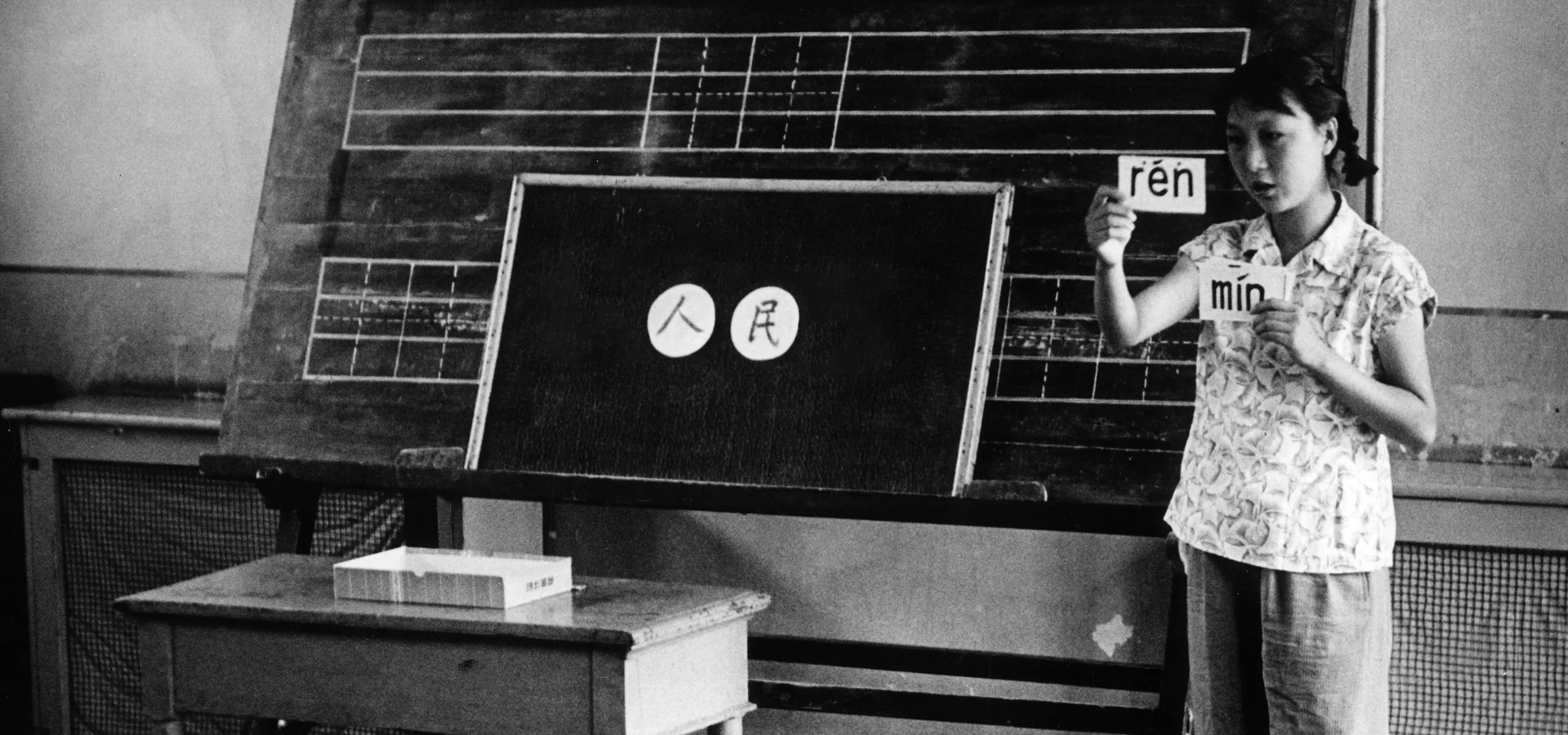

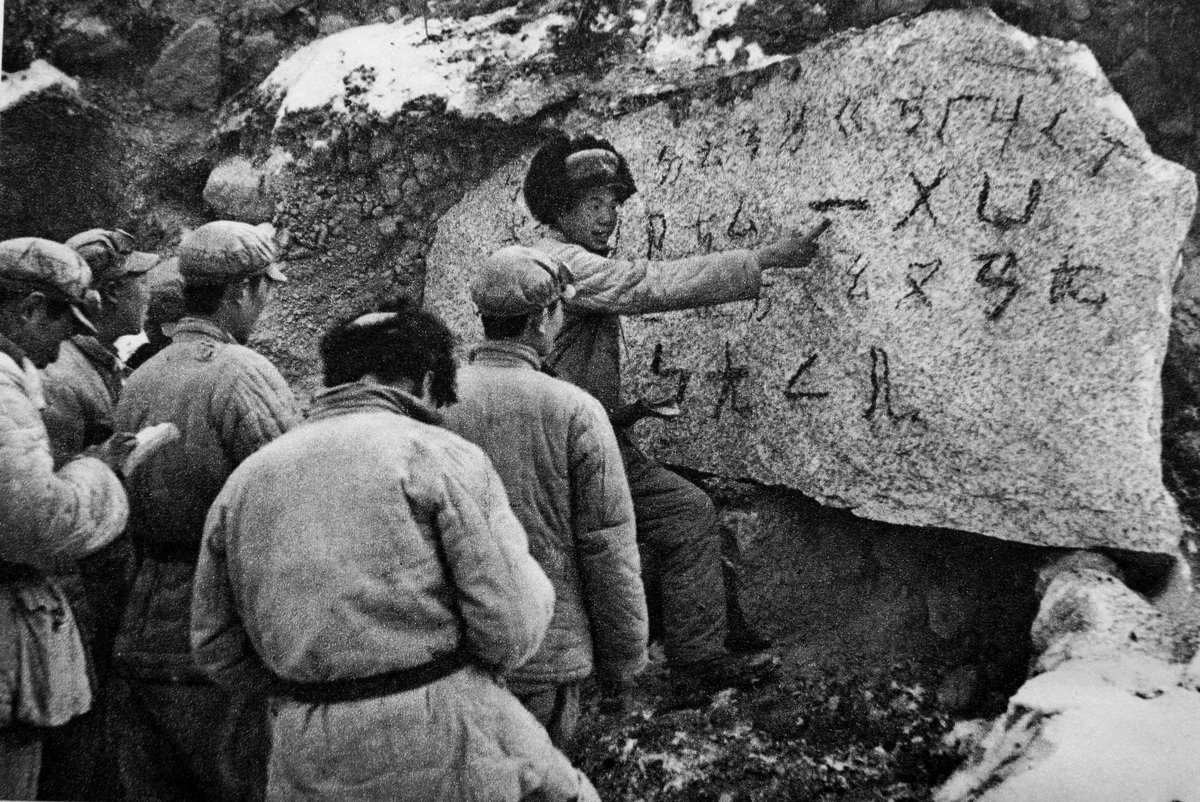

Since the 1970s, various efforts have been made to design codes that pair either Chinese character components or phonetic symbols with Latin letters so that the roughly 70,000 characters in the Chinese language can be typed out. These pairing systems are arbitrary; anyone can create their own as long as it fits into computer memory.

Chinese IMEs are generally based on either character shapes or sounds. During his time in prison during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s, physicist and engineer Zhi Bingyi designed “Zhi Code,” which used Latin letters and Arabic numerals to describe the shape and structure of Chinese characters. Zhi Code laid the groundwork for modern Chinese input methods, and in the 1970s and ’80s, hundreds of stroke- or radical-based IMEs were invented. While the assignments for each character part might seem random, the goal was to make the system easier and faster for computers to process and for humans to master.

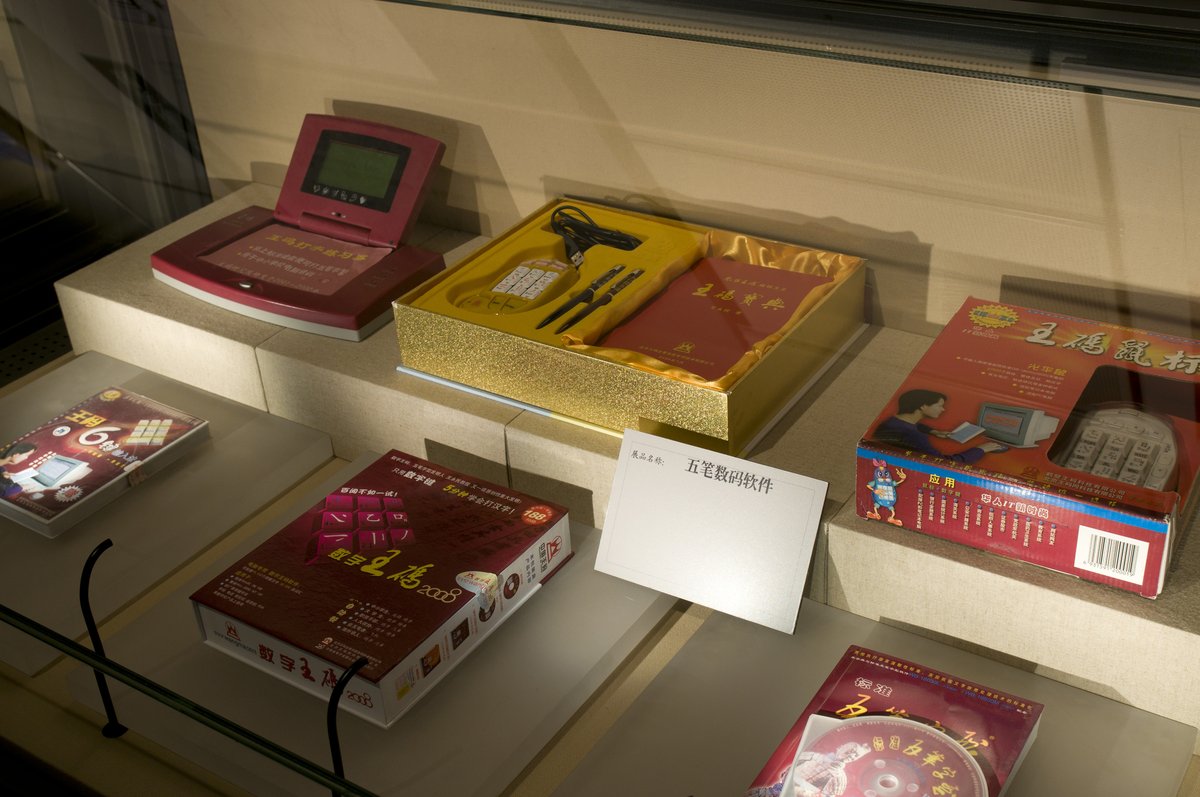

Cangjie and Wubi are probably the most common Chinese IMEs based on characters’ shapes. Mostly used in Hong Kong and Macao today, Cangjie IME was invented in Taiwan in 1976 by computer scientist Chu Bong-Foo and named after the mythological inventor of the Chinese writing system. Wubi, on the other hand, remained dominant in the Chinese mainland throughout the 1980s after its invention by programmer Wang Yongmin in 1983.

By the time I went to school in the early 2000s, pinyin IME was the only system taught and the first thing we learned in Chinese and computer classes. For a long time, I thought it was the only way to type Chinese. For simplified Mandarin, the official script of the Chinese mainland, it is the most commonly used typing method by far.

In Taiwan, however, zhuyin (also known as Bopomofo) is more popular. Also sound-based, it uses special symbols representing Chinese phonetics instead of the English alphabet. The zhuyin symbols, consisting of 37 characters and five tone marks, were created in the 1910s, four decades before pinyin, which was officially adopted by the Chinese government in 1958. Taiwan continued to use zhuyin, which is taught in elementary schools to this day.

Computer engineers were initially reluctant to create input methods using the phonetic script. “[They] thought of pinyin as the absolute worst option available to govern the human-computer interaction of Chinese input,” Mullaney told me when I called him recently. “They’re really ambiguous because there are many Chinese characters with the same pronunciation, and there are a variety of other complexities.”

While many structure-based IMEs only require fewer than four digits to type out a character, pinyin IMEs theoretically necessitate spelling out the full phonetic values. Mullaney writes in his book that the full phonetic spelling of Chinese characters leads to input strings that are more than 15 percent longer than structure-based systems. Moreover, some pinyin spellings may encompass multiple different characters, such as “shang,” which also includes the words “sha” and “shan,” requiring the computer to be more robust in disambiguating whether typing is complete or ongoing. Graphical methods, on the other hand, include disambiguation, as codes are arbitrarily assigned to each character, radical, or stroke. In short, pinyin is computationally demanding and inefficient.

Finally, sound-based systems usually have a pop-up window that appears as you type, offering a selection of characters to choose from. As a child, I loved the pop-up window and would download different themes to match my mood for the day. But selecting each character slowed things down, especially when I first started to learn pinyin IMEs.

The rise of pinyin

So how did pinyin overtake Wubi as the most common IME on the Chinese mainland? To understand others’ experience typing with Wubi, I called my aunt. Born in the late 1950s, she spent nearly two decades working in a bank in my hometown in Anhui province. In the late ’90s, when the internet began to spread beyond universities and research institutions in China, bank clerks like my aunt were required to learn and pass tests on how to conduct banking operations digitally.

My competitive aunt took the test seriously. She taught herself the Wubi method, memorizing the codes associated with the construction of Chinese characters. She also bought dictionaries to learn how to divide characters into different radicals or strokes. “I thought it was peculiar and fun,” my aunt told me over the phone recently. “I sometimes typed faster than my younger colleagues who used pinyin IMEs. There were times that I only needed one keystroke to get a character typed.”

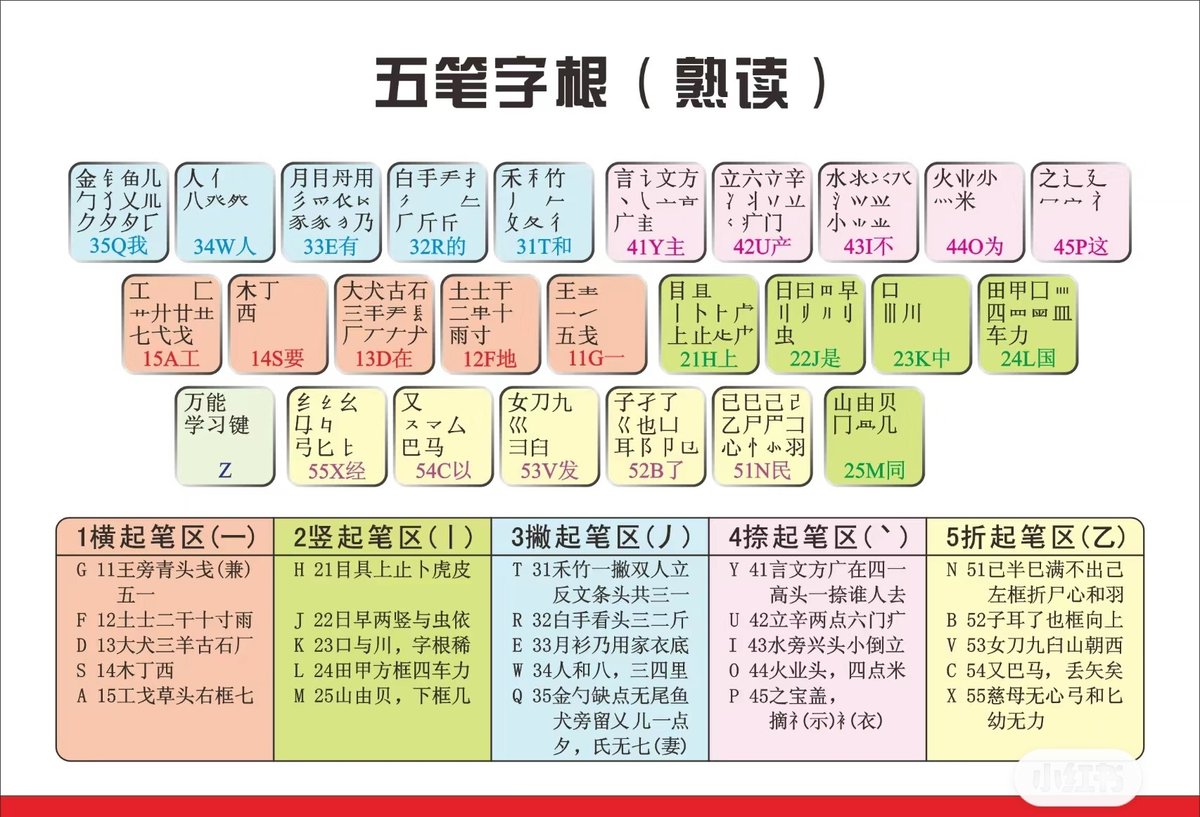

With Wubi, users press at most five keys to lock a unique Chinese character, and while duplicate codes exist, there are far fewer than homophones, meaning the time spent choosing the correct word is significantly reduced or sometimes eliminated altogether. To make typing faster, Wubi assigns a single letter to 25 common characters. For example, to type 我 (meaning “I”), the full code is TRNT, but it is also assigned the hotkey of a single “Q.” With practice, it’s possible to type without looking at the keyboard or the screen, reaching speeds of up to 293 characters per minute.

She said Wubi worked particularly well when typing customers’ names and addresses. Even if you didn’t know a character or its standard Mandarin pronunciation (as can be the case due to China’s numerous local dialects), Wubi would still allow you to type it out using the codes for each stroke.

In the 1980s, the Chinese State Science and Technology Commission and the Commission of Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense issued official government papers to promote the Wubi IME nationwide, including in the military. Training workshops to teach the method mushroomed, and many domestic computer keyboards at the time featured both the English alphabet as well as Wubi radicals to facilitate learning.

My aunt used to keep a Wubi table and dictionary at the bank in case she forgot the association between a character and its respective code. But after practice, she soon memorized them by heart. Even today, more than a decade after retiring, she can still type in Wubi.

In the end, however, the steep learning curve to remember codes for each radical gradually deterred people from learning Wubi. And since the 1980s, younger generations have studied pinyin in school as part of Chinese language classes, making it easy and natural for them to master pinyin IMEs. Many pinyin-based IMEs were invented in the 1990s, including Zhineng ABC, which was built into Microsoft Windows.

Input domination

It wasn’t until the 2000s that pinyin IMEs truly surpassed Wubi. As internet use grew and technology developed in China, systems began to learn and predict common words or phrases, reducing the need to manually select each character. Although Wubi is more efficient for typing individual characters, pinyin IMEs are faster for typing words or phrases.

In 2006, internet giant Sogou launched its pinyin input method system based on its search engine, greatly expanding its digital vocabulary. Sogou’s input quickly became the favored input across the country thanks to features such as predictive text, auto-completion, and records of high-frequency words, allowing users to type with abbreviations or shortcuts. According to consultancy firm iiMedia Research, over 72 percent of people in China now use pinyin, while less than 14 percent use Wubi.

Now retired, my aunt only uses her smartphone and iPad and mostly writes characters out on the touch screen or sends voice messages. The same goes for my mom; she doesn’t remember pinyin well from school, which was interrupted by the Cultural Revolution. Becoming a stay-at-home parent in the late 1990s, she never had to learn IMEs for work. And before touchscreen phones emerged in the late 2000s, she never sent messages, preferring to make calls on her basic mobile phone.

In the digital age, reliance on digital typing has significantly increased. The development of AI tools and advanced technologies has made typing easier than ever, with features like suggestions, predictions, and user habits recorded in real time. Emojis, voice messages, and internet slang have also flourished in the digital world.

“With generative AI making strides each passing week, it’s pretty clear that Chinese IMEs are just going to get faster and more accurate,” Mullaney tells me, adding that current prediction features have enabled Chinese typing speeds to reach up to 1,800 characters per minute. “What’s momentous—and a bit unsettling—about AI, is how it violates the long-held ‘speed limit’ of human-computer interaction: the speed of human intention,” he adds. According to Mullaney, AI-augmented input has made the concept of “words-per-minute,” the traditional metric to measure productivity and compare writing technologies, start to lose all meaning.

The reliance on digital typing and pinyin IME has also led many people to forget how to write certain characters by hand. When I kept a diary, I often found myself unable to recall how to write a character correctly. Now I usually jot down my thoughts in a phone app, further reducing the need to write.

This phenomenon is the same around the world; however, the complexity of Chinese characters presents unique challenges in the digital realm. For example, some intricate characters can’t be found in digital dictionaries, leading to their gradual disappearance. At the same time, people or places whose names contain rare characters are sometimes forced to change them in order to live comfortably in the digital world. Fortunately, efforts are being made by the government and tech giants to save and add these uncommon characters into the digital realm.

Overall, the evolution of Chinese input methods reflects broader technological and societal changes. From the early days of shape-based methods to the widespread adoption of pinyin IMEs, each generation has adapted to the tools available, balancing efficiency with the complexity of the language. It’s essential to consider how these advancements affect cultural heritage, too. By understanding the history and development of Chinese input methods, we can better appreciate the intricate balance between tradition and innovation. Ensuring that the richness of the Chinese language continues to thrive in the digital age will require thoughtful integration of new technologies alongside the preservation of traditional writing skills and character diversity.