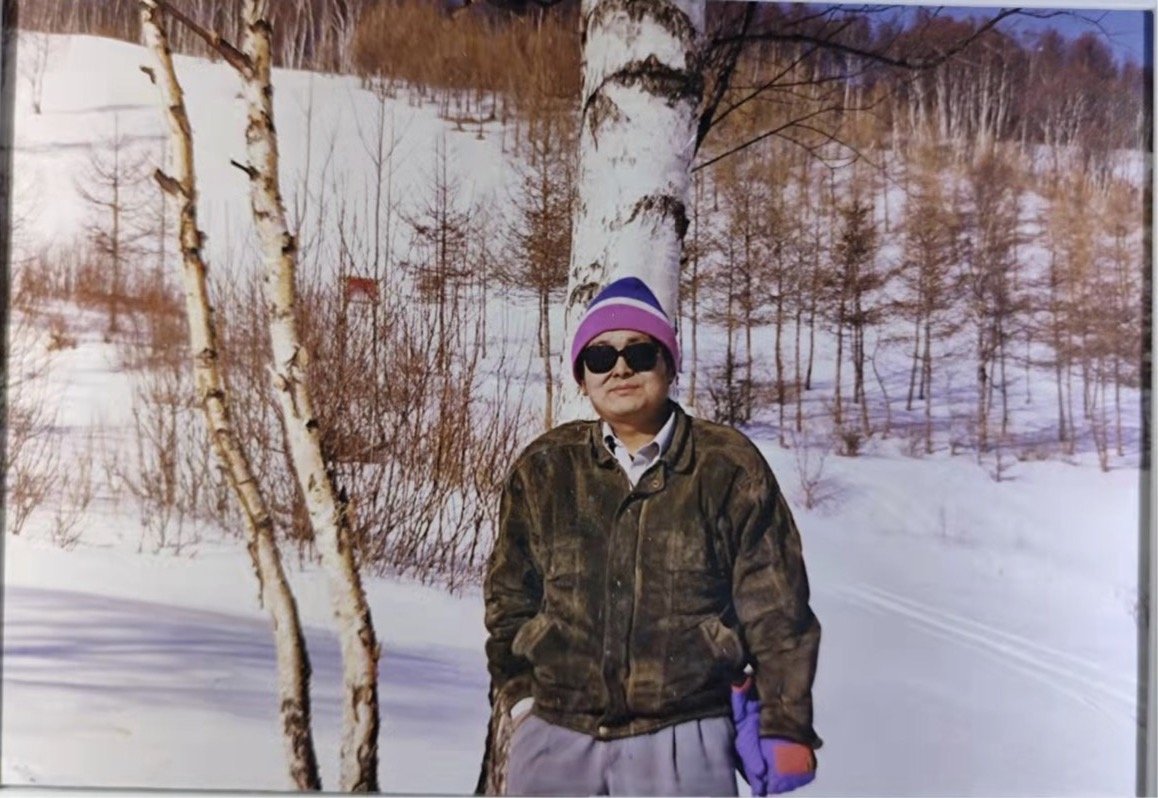

Opened in 1997, the Saibei Resort in Chongli county introduced China’s first generation of ski enthusiasts to the sport

Over the past two weeks, China has hosted a flurry of events in Beijing and Zhangjiakou for its first Winter Olympics.

Since Beijing made its successful bid to host the Winter Olympic in 2015, the number of nationwide winter sports participants has reached 300 million.

In particular, skiing—already widespread in Europe and North America—is gradually becoming popular among young people in China. But in Chongli, Zhangjiakou, which hosts this year’s ski events, the sport was still totally unknown to the locals 26 years ago. There were no resorts or skiers to be seen anywhere in Chongli county.

Today’s story is about what has happened during those intervening years.

-1-

A mysterious sport

Wu Ma: My name is Wu Ma. I’m a documentary filmmaker from Beijing.

It feels like it snowed more when I was a kid than it does now. Back then, whenever it snowed, my buddies would meet up at the Temple of Heaven for a snowball fight. We would fight until dark, until our underclothes were soaked in sweat and our coats were covered in a layer of ice from the melting snow.

As far as I remember, I first encountered skiing through foreign films and advertisements. I had an older cousin who was a sports enthusiast who studied music in Switzerland. He once sent me a photo of himself skiing, and a ski hat.

The photo captures him in his element, carving a beautiful arc on the slope and sending up a spray of snow.

At that time, Chinese people had no clue what skiing was, especially those outside of the three northeastern provinces. To us, it was a very mysterious sport.

In the winter of 1997, I saw an ad in the evening papers, about the size of a block of tofu: “Experience Nature, Go Skiing!” It was an ad for the Saibei Ski Resort.

I had no idea where this place was, and knew nothing about skiing. But I thought of the filmmaker Wang Shuo’s words, “What do we fear most in life? Isn’t it living in vain?” So I had to give it a try.

The ski resort that Wu Ma saw advertised was located 240km outside Beijing in Chongli county, Zhangjiakou, Hebei province.

If you had told the locals that this rugged, impoverished county would 26 years later host part of China’s first Winter Olympics, nobody would’ve believed you.

Turning the gears of fate for this legendary “Snow Kingdom” was a man who became somewhat of a legend himself.

-2-

Uncharted territory

Guo Jing: My name is Guo Jing, and my courtesy name is Daxia. I’m 62. I’m the founder of the Saibei Ski Resort, the first ski resort in Chongli county.

In 1996, I was the chairman of a company in Beihai, Guangxi. People often came asking me to invest with them. One day out of the blue, someone recommended a skiing project in Zhangjiakou, Hebei, saying I should come check it out.

Back then, China’s ski resorts mainly used natural snow: Yabuli, Beidahu, Changbaishan, and so on. They were concentrated in Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces in the northeast. This meant that most parts of China could not have ski resorts, due to their climate.

At the time, Zhangjiakou was still considered an impoverished area by the government. Due to tensions with the Soviet Union, it had long been closed off to the rest of the world as a military staging area. So the first time I went to Chongli, I didn’t take it very seriously—it was just for fun.

As luck would have it, I was accompanied on that trip by Shan Zhaojian, the director of the China Ski Association and a senior figure in Chinese skiing. In 1957, when he was 19, Mr. Shan became China’s first ski champion. He also eventually became one of the experts who helped select the resorts at Chongli for the 2022 Winter Olympics.

Back then, Mr. Shan and his colleagues had long wanted to find suitable ski areas near Beijing. I listened to him talk the whole way up, getting a basic understanding of skiing. The picture in my mind was the war hero Yang Zirong in the movie Tracks in the Snowy Forest, sliding over the snow with two poles for support.

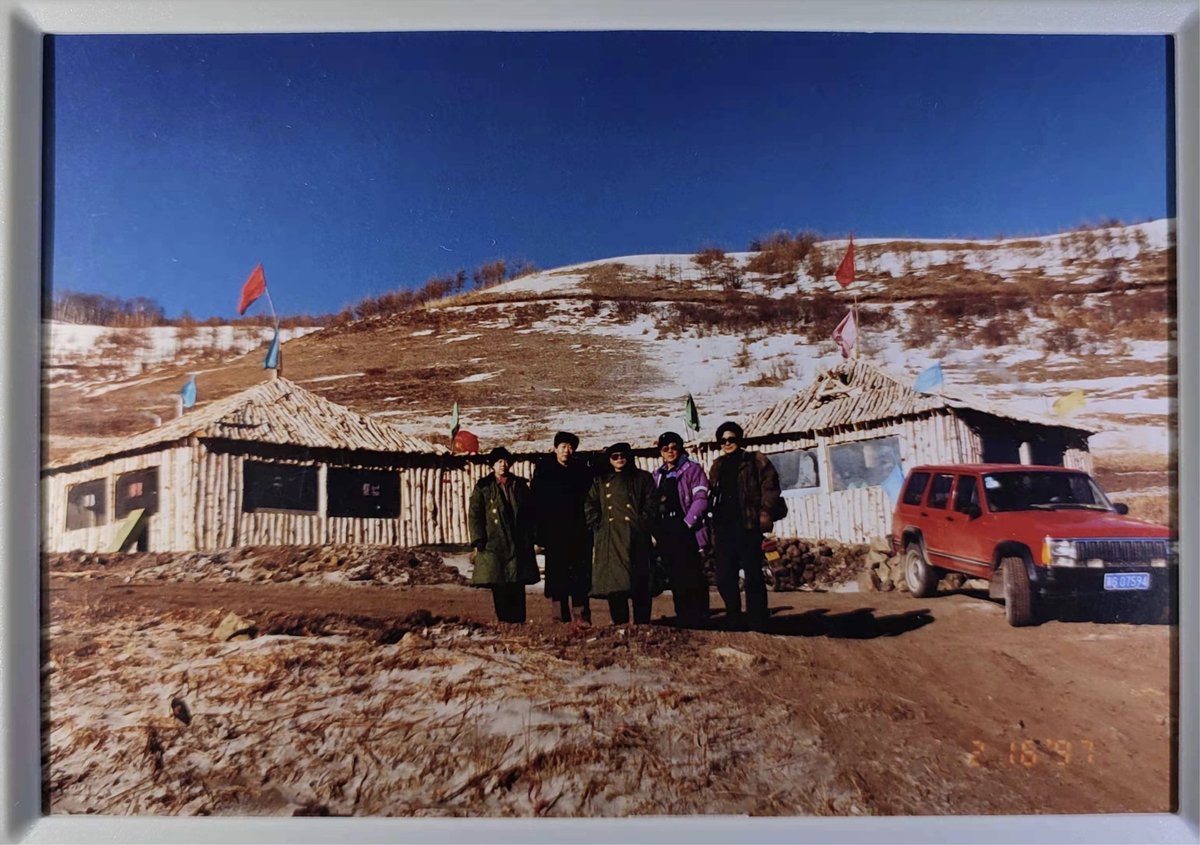

Chongli, at the time of my first visit there, was truly a backwater. There were few proper buildings and only a single road; not even with any traffic lights. They showed us all around the mountainous areas.

It was barely September, but Chongli already had the feel of Beijing in late autumn, with the birch and larch forests turning yellow. As we went around the mountain, Mr. Shan kept telling me: The slopes here are gentle, the vegetation is thick, and the water is abundant; there is plenty of snow in winter, and it lasts on the ground for a long time—it’s perfect for a ski resort. And it wouldn’t be such a big investment; if I really wanted to do it, I would have the Ski Association’s support.

To be honest, I had trouble taking in this information, mainly because there wasn’t any snow yet. As soon as I got home, I forgot all about it.

A few months later, at the end of November, they came to me again and said, “It’s snowing!” I thought, no way, it’s still 10 degrees out in Beijing.

The local representative and I headed back to Zhangjiakou in an old Volvo. The memory is crystal clear: About halfway there, the road signs disappeared. I asked the representative which way we should go, and he said he didn’t know—he usually took the train or bus.

At that moment, a peculiar feeling came over me. I felt as though I was making an expedition into the unknown, and not even my guide knew where we were going. The “road” ahead of me was going to be filled with uncertainty.

Going by instinct, I found a road that took us to Magpie Ridge, the future site of the ski resort. The snow was up over our ankles, over a dozen centimeters. There was something magical about the place. On an impulse, I decided to start the resort.

The snow season was almost upon us, so we had to hurry to make our debut.

I took the plunge and put up a few hundred thousand yuan. Mr. Shan supplied 100 pairs of second-hand skis and 20 snowsuits.

I wanted to use the most primitive means to bring people close to nature, so we simply cut down some trees to make a few runs, without snow machines or grooming equipment. Honestly, it was a stretch to call them runs—we didn’t even remove the tree roots.

But the good thing was that we had natural snow. You could ski wherever there was snow. There weren’t many limitations.

I also took advantage of local materials, using birch wood to make a few hexagonal huts. Later, people always said they reminded them of yurts. We used these huts for equipment storage and as rest areas. When it was 20 or 30 degrees below zero outside, you could have a fire inside and be very cozy.

I took the name Saibei, “North of the Frontier,” from the popular song, “I Love the Snow on the Frontier’s North,” and advertised it on pagers and in newspapers to recruit tourists.

On New Year’s Day, 1997, Saibei Ski Resort opened for business.

-3-

Fun in the wilderness

Wu: I was in the first group of visitors to Saibei.

The ski resort told us to meet at a hotel on North Third Ring Road at 6:30 a.m. on a Saturday. The roads were a far cry from the highways of today—we drove a full seven hours, arriving after 1 p.m.

We parked the cars on a ridge. When we got out, we saw a few shabby yurts full of second-hand ski equipment. The yurts were dirty and piled with snow.

There was a van parked outside, and we all squeezed in with our skis and started driving up the mountain. A thin man in his 50s or 60s introduced himself: “My name is Zhao Shilu and I’m your ski instructor today. Welcome to Saibei!” Only later did I find out that he was the head coach of the armed ski patrol.

He was full of enthusiasm, saying, “I’m going to read you a little poem I wrote: The Northern snows stretch toward the sky, the athlete’s spirit won’t yield the fight…” Anyway, it was a rhyming verse, something along those lines. We all clapped in our padded mittens.

When we reached the top of Magpie Ridge, we were surrounded by pine trees. The areas that were without trees were the ski runs. It was all wild, ungroomed snow.

Then Coach Zhao started teaching us how to ski. Once everyone had skied down the mountain, they’d bring us back up, and we’d go down again. We did this over and over until sunset.

Skiing is very physically demanding, because it takes a lot of strength to control your skis. We were all exhausted when we got down from the mountain. There was a place called the White Birch Lodge, a bare-bones hostel. Many of the rooms didn’t even have windows. We ate a piping hot buffet dinner, and went to sleep.

The next morning, we went back up to ski, had lunch, and then bused back to Bejing in the afternoon. We really only skied for two half-days, ate three meals, and stayed one night. In 1997, this trip cost 700 yuan—a pretty steep price for the time. It was definitely a luxury sport. And even though the conditions weren’t great, I started going at least twice a month because it was just too much fun.

You’re standing on a mountaintop with the wind blowing, and a vast expanse of forest and snow before you. The dopamine thrill of going down the mountain, the speed, and the wind rushing past your ears—it was a wonderful feeling.

Later, several ski resorts that used artificial snow opened up in Beijing. I’ve been to all of them. At the top of the slope, there’s only the white run surrounded by yellow dirt—you can’t help but feel it’s too contrived. But out in Saibei, all around you there was a world of ice and snow.

-4-

China’s ski pioneers

Guo: Saibei’s first snow season lasted until March of 1997. There was a news report under the headline, “Tomorrow the Insects Wake,” depicting the renewal of life in spring everywhere else while Saibei Ski Resort remained a snowy wonderland.

Apart from the excellent natural conditions, in those years you could also experience elite-level ski training at Saibei.

Out of his love for skiing, Mr. Shan introduced us to many veteran coaches and athletes. China’s ski program was still weak at the time, so they all wanted to help popularize the sport.

Wu: Though my own skills were mediocre, all of my instructors were famous athletes. Like Coach Zhao, the head coach of the armed ski patrol; and Guo Dandan, China’s first world champion in skiing; they’ve all been instructors at Saibei. Without them, I don’t think Beijingers would have been exposed to the world of skiing.

Birds of a feather flock together. That first group of skiers were people who could find joy in adversity. They had two things in common: decent financial means and a thirst for adventure.

I met all kinds of people at Saibei: amateur racing drivers, paragliders, and future ski champions. There were also business-minded people among them, who saw the potential in skiing, opened resorts and equipment outfitters in the surrounding area, and gave impetus to China’s ski industry.

You could say that the Saibei of that time felt like the first graduating class of the Whampoa Military Academy, where so many of the nation’s future leaders studied in the early 20th century. Saibei cultivated a group of passionate skiers and raised the public profile of the sport.

Guo: Saibei reached its peak in popularity around the turn of the millennium. In those days, we used to run special trains that could bring 1,000 guests to the resort a day, and sleep 350 people a night in our 250-bed hotel.

In 1999, the Shijinglong Ski Resort opened in Beijing. It was the first Chinese ski resort to rely on artificial snow.

From there on, artificial snow resorts took off. Saibei’s facilities were rudimentary compared to these newer resorts.

In 2003, the Wanlong Ski Resort opened in Chongli, with 30 million invested in the first year and 60 million in the second. This had an even larger impact on Saibei.

Wanlong Ski Resort was built with the investment and supervision of Holiland vice-chairman Luo Li. He started out as a ski enthusiast, also frequenting Saibei around 2002. But Saibei didn’t have chairlifts yet, so skiers had to wait in line to be shuttled up the mountain in utility vehicles. Luo felt this was too time-consuming, so he gave the resort staff a sum of money to purchase a private vehicle for him to use when he visited.

The next year was when the SARS epidemic, so Luo took this car all over Chongli, finally selecting the site that became the Wanlong Resort. Wanlong remains the largest and best-equipped ski resort in North China.

From 2003 on, the ski industry has surged in and around Beijing. Within the city, there are Shijinglong and Nanshan, artificial snow resorts that take advantage of easy access to the capital. In Chongli, there is the Changchengling Ski Resort, developed under the auspices of the Hebei Sports Bureau. And of course, there’s also the professionally-designed, luxurious Wanlong Resort.

Guo Jing and Saibei might as well have been ants in a herd of elephants. They needed to use every trick in the book to survive.

-5-

Twilight for Saibei

Wu: Guo Jing is an interesting guy.

I think he must’ve been a successful entrepreneur early in his career, but when I met him, he didn’t look at all like a well-off businessman. He always wore an old jacket, with his hair long, a pair of black-rimmed glasses, and a handbag under his arm. He looked like some foreman in a labor crew, hounding the boss to pay up.

But he was very pragmatic. Back when Chongli was too impoverished to have running water or electricity, he built roads, asked the government to put in utilities, and finally made his ski resort. Just think about how much he did.

Later, when he ran out of money, he once called me up to ask if I could find a way to sell his stamp collection and scrape together some project funds. But I wasn’t able to help.

I think he has a kind of obsession, a need to see a project through to completion. He is that kind of person. From a money-making perspective, he would have succeeded long ago if he’d put this level of investment into something else.

I stopped going to Saibei after things got busy at work. During that period, the resort went through another period of significant development. Guo partnered with a company called Dolomiti, a famous ropeway manufacturer from Italy. It wasn’t until this collaboration started that Saibei had chairlifts on any meaningful scale.

Guo: Both sides had high expectations when we partnered in 2006. I hoped that they could give old Saibei a new face, and that we could ride the popularity of their resorts in Europe to reach a new level.

But in the end, they lost over 100 million and fled in defeat. It was funny timing, right on the eve of the announcement of the 2022 Winter Olympics host city.

They blindly pursued modernization—of course, they also introduced China’s first high-speed chairlift and sound design principles. But they had blind confidence in China’s market without an understanding of local conditions.

For example, they made the ski rental area very small. This is normal in Europe, where people want personalized service and everyone has their favorite ski shop. But it’s different in China, where people want things to look impressive. They insisted on creating a European flavor, but not many people here have even been to Europe.

Wu: The last time I went to Saibei was three or four years ago, when I took my daughter there.

The place had changed a lot. The White Birch Lodge was no longer there; they’d built a new hotel covered in huge billboards. There was no resemblance to the Saibei I remembered.

Back then, skiing was just one aspect of the experience. Out in nature, when you were at the peak of the mountain, you could look into the distance and see the county town and local roads. Now and then, a car would go by, or a villager on a motorbike stocking up for the Lunar New Year. It took you out of the frame of your daily life.

When I went, I could also see my friends: chat with old Mr. Guo, and try the local beef noodles. Those are all cherished memories.

I rarely go skiing anymore. There are too many people, and it’s a waste of time.

As the Olympics approached, Chongli’s snow season has gotten busier each year.

At the end of 2019, a new rail line opened ahead of the Olympics. It now takes only an hour to get to Chongli from Beijing. The trains on this line even have special compartments for ski equipment.

Zhangjiakou now has nine ski resorts that receive a total of 3 million visitors each winter.

In 2014, Chongli lost its poverty designation. As the town kept pace with development, its atmosphere has increasingly come to resemble Beijing’s.

But people don’t notice that the natural snowfall in Chongli is decreasing year after year - just as they don’t notice, when they head up to Chongli for another snow season, that a legendary old ski resort still lies dormant in the valley.

-6-

What’s next for the dormant resort?

Guo: The way I see it, partnering with the Italians was Saibei’s last chance. By then I already recognized that in this economic climate, in this environment of irrational consumption, I was getting farther and farther away from my initial vision.

With losses mounting, I temporarily closed Saibei, opening only occasionally to sell lift tickets for Dolomiti. This went on until 2013.

Since then, I’ve done travel planning all around the country and gradually paid off the debt. Let Old Saibei sleep for now—it may rise again in the future.

Wu: Everything has a beginning and an end. With increasing capital investment and stronger government support, the market will change. But even if Saibei gets left behind, its significance is undeniable.

Without Mr. Guo and the Saibei of yesterday, without the passion of instructors like Coach Shan and Guo Dandan, we wouldn’t have today’s Chongli. I would go so far as to say that without them, China wouldn’t have been able to host the Winter Olympics.

Guo: Last December, just before the Winter Olympics started, I returned to Saibei with a journalist from CCTV.

Below the Birch Lodge, the weeds had already grown as tall as our heads, blocking off the road. The bar and terrace I had chiseled from stone were falling apart. China’s first snow-maker, its first chairlift, its first grooming machine, and the jeeps we used to bring people up and down the mountain were all still standing there quietly.

I stood in front of Snowman Lodge, the icon of old Saibei, and thought over these past 20 years. I want to build a monument here someday, in the shape of a pair of skis.

I already know what I want it to say:

“There is no winter that can quell the fires of my spirit.

“Forget success; I’m here to open new horizons.”

This story is published as part of TWOC’s collaboration with Story FM, a renowned storytelling podcast in China. It has been translated from Chinese by TWOC and edited for clarity. The original can be listened to on Story FM’s channel on Himalaya and Apple Podcasts (in Chinese only).