Alice Poon’s historical novel is an evocative, socially conscious reimagining of four famous women in the late Ming dynasty

If the Marvel Cinematic Universe has taught us anything, it is that a good team-up is the best way to juice a genre. While Liu Rushi (柳如是), Dong Xiaowan (董小宛), Li Xiangjun (李香君), and Chen Yuanyuan (陈圆圆) may not require the same level of CGI as The Avengers franchise, they are just as celebrated in Chinese literature as The Incredible Hulk is in comic books and summer blockbusters.

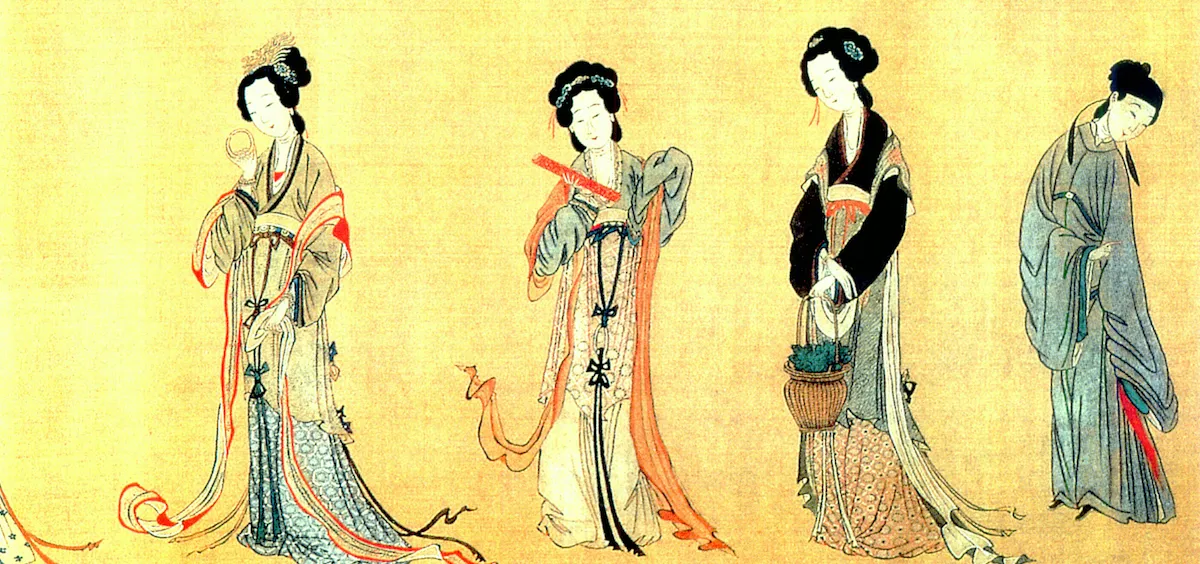

The sensational lives and loves of these four remarkable women—all of them courtesans living in the demimonde of the late Ming era (1368 – 1644)—have been the subject of poems, novels, plays, operas, and more than a few telenovelas. Yet, few authors have attempted to explore the internal lives of these women despite their fame.

Hong Kong-born, Vancouver-based writer Alice Poon has made something of a career filling in the emotional backstories for some of China’s most famous and misunderstood women. Her 2017 novel The Green Phoenix speculated about a love triangle at the heart of the Manchu conquest of China and the courtly intrigues of the first Qing emperors.

In her latest book, Tales of Ming Courtesans, Poon returns to the convulsions and upheavals of the 17th century Ming-Qing transition. Many of the figures who played a role in the collapse of the Ming dynasty, the Qing conquest, and the Chinese resistance to the Manchus are characters in Poon’s novel: including rebel leader Li Zicheng (李自成), turncoat general Wu Sangui (吴三桂), and loyalist Ming scholars Chen Zilong (陈子龙), Qian Qianyi (钱谦益), and Hou Fangyu (侯方域). But Tales of Ming Courtesans turns around the usual tropes, relegating the “great men” to the sidelines and centering the story around the actions and agency of the women they loved.

As with any good team-up, the trick is how to weave the stories of already famous protagonists into a single coherent plot. Poon uses a fictionalized version of Liu Rushi’s daughter, here named Jingjing, as a loose thread to bind the narrative together. In the novel, Jingjing learns about the lives of Liu and her amazing friends while puzzling out a mystery of family lineage whose solution is at the heart of Poon’s story.

The book opens in 1664, not long after Liu’s suicide (legend has her hounded to death by the creditors and political enemies of her late husband, the scholar Qian Qianyi). Liu has written a memoir and left it to Jingjing. Seeking more information about her mother’s life, Jingjing travels to Yunnan, where she meets Chen Yuanyuan, famous as the lover of the general Wu Sangui, who collaborated with the Manchus during their conquest of China in 1644.

Jingjing learns about the eventful, if often tragic, lives of Liu and Chen while also listening to stories of their fellow courtesans Li Xiangjun, one of the two main characters of the celebrated Qing-era play The Peach Blossom Fan, and the poet Dong Xiaowan. The memoiristic structure allows Poon to keep a first-person narrative throughout most of the book even as she shifts points-of-view between different characters.

There is little historical evidence that the four women of Poon’s work knew each other in reality. Still, they shared a level of fame and all were intimately connected to the world of courtesan culture which flourished in cities like Nanjing and Hangzhou in the late Ming.

Poon’s novel takes delight in imagining an alternative history in which the four most famous women from this period worked together to shape some of the era’s defining events. In Poon’s telling, the women are no mere muses, femme fatales, or distressed damsels; they are women with agency and ideas striving to overcome social stigmas and prejudice. At the end of the novel, the young Jingjing resolves to follow their example and sets out to become a social reformer.

As in The Green Phoenix, Poon is lavish in period details: The descriptions of food, clothing, homes, music, and art all attest to the extent of her attention to historical aesthetics. Non-specialists in Chinese history and art might occasionally wish the publisher had included some maps or illustrations. Still, Poon’s writing is so evocative of a time and place that even Chinese history novices could get swept away without, for example, being able to visualize the specific characteristics of different calligraphic scripts. She also ably utilizes the work of scholars and other writers, including the scholar Mao Xiang (冒襄), a contemporary of the four women, and who is usually associated with Dong Xiaowan.

Tales of Ming Courtesans remains, however, very much a work of fiction. Poon endows her characters with a degree of social consciousness that borders on anachronism. While it is possible these historical figures may have held iconoclastic views for their time, repeated speeches denouncing (among other things) foot binding, the eunuch system, concubinage, peasant exploitation, prostitution, and social caste inject a presentism into the narrative that can occasionally be jarring.

The characters chafe at being labeled and, in many cases, officially registered as jianmin (贱民), meaning they have a debased social status. Historian Wai-yee Li, in her annotated translation Plum Shadows and Plank Bridge: Two Memoirs about Courtesans, which was published last year and features writings about many of the same women featured in Poon’s novel, argued that despite their lowly social classification, courtesans “consorted with elite men, sometimes as intellectual equals, and could claim respectability through marriage.” The courtesan was a liminal figure, straddling the respectable realm of elite culture and the genteel debauchery of the pleasure quarters. Elite men pined after them, but the courtesan, no matter how talented or beautiful, remained at least officially off-limits for marriage or even concubinage.

For all of the songs and stories of romantic love between scholar and courtesan, the reality of the world of the Ming courtesan was firmly rooted in commercialized sex and the commoditization of female bodies. The silk garments, poetry, music, and repartee obscured the transactional nature of these relationships, just as the courtesans’ “right of refusal” provided a thin veneer of respectability for an eventual consummation.

Poon is writing a romance, not a documentary about sex workers in the late Ming. The four main protagonists exhibit no superpowers except for the ability to remain—mostly—chaste while immersed in a world of commercial sex. Love is real and powerful. Consummation is bestowed consensually on cherished lovers, except when it isn’t, and Poon weaves gossamer phrases of stylized sex, except when she doesn’t. A few scenes of sexual violence remind the reader that for all the fame and fairy tales, the women in this world faced genuine dangers to their physical and emotional well-being.

Fans of frothy historical romances threaded with a subtle modern sensibility will enjoy Poon’s journey back to the late Ming. Though the super courtesan team-up probably never existed, it’s still fun to imagine the historical possibilities if it had—such is the liberating fun of reading a novelist who is also a historian. With characters as rich as these and a writer as expressive as Poon, who needs CGI, anyway?