A 28-year-old idol’s dimming popularity has cast a cruel light on the fickle world of celebrity

He was once dubbed China’s Justin Bieber. But Lu Han might soon end up China’s Kevin Jonas, if current trends continue.

The influence of the 28-year-old singer-actor, who has over 58 million followers on Weibo, is in decline, observers say. Given that Lu was once the leading light of the “little fresh meat” phenomenon—male stars primarily famous for being young and good-looking—this is a big deal.

It was in October 2017 that Lu first decided to take his personal life public. “Hello everyone, let me introduce you to my girlfriend Guan Xiaotong,” Lu enthused to his followers. Within an hour, the announcement had been shared over 1.2 million times, receiving nearly 3 million comments. The traffic sent Weibo into near-meltdown for several hours.

At that time, the emotional earthquake was regarded as a proof of Lu’s stunning influence. But nobody seemed to have considered the long-term consequences. Though, over a year later, Lu remains China’s top star in commercial value, according to entertainment research firm AIMan Data, his public support has slumped: This July, TV drama Sweet Blow, co-starring Lu and his girlfriend Guan, received the lowest audience-rating in the history of the Hunan Television channel. In October, it was reported that scalpers selling tickets for Lu’s concerts couldn’t find buyers even at heavy discounts. A few days later, Lu’s agency canceled the Zhengzhou stop of his tour. At that point, Lu had appeared on the cover of only one mainstream magazine in the whole year.

Was the heartthrob losing his popularity, many wondered? And not just teenage fans, but Weibo watchers, students of mainland pop culture, and, presumably the dozens of companies and brands whose livelihoods are, in some way, entwined with the star.

“Lu Han has lost some fans, that’s true,” 25-year-old fan Qiqi tells TWOC, “but, as the proverb goes, a starved camel is still bigger than a horse; [Lu is] still a top ‘traffic star.’” In recent years, “internet traffic star (流量明星)” has become a standard media term for celebrities with a huge base, influence, and commercial value, with Lu always among the first examples named.

Lu initially flew to fame in 2012 as a member of K-pop boy band EXO. Two years later, he filed a lawsuit against Korean company SM Entertainment to void his contract, and came back to pursue a new solo career in China.

To celebrate his homecoming in 2014, Lu’s fans gifted him over 100 million comments on one of his Weibo posts, a number subsequently recognized as a Guinness World Record. “He already had a great number of fans before he came back to China,” explains Xiao Yao, a 22-year-old fan of Lu. “Then, after he joined [the Chinese edition of variety show] Running Man, he became well-known nationwide.”

From 2015 to 2017, Lu appeared on the cover of over 20 magazines including Elle China, GQ Style, and Forbes China, and officially endorsed over 20 brands. By 2017, he was ranked second on the Forbes China Celebrity 100 list—the top male celebrity, only behind A-list actress Fan Bingbing.

Such was the speed of Lu’s rise, it created the term “Lu Han effect,” referring to the tremendous ripple effects that “traffic stars” can provoke even for their most trifling actions. In April 2016, Lu posted a photo of himself leaning on an innocuous mailbox in Shanghai; it immediately became a tourist attraction.

Well-known financial columnist Wu Xiaobo has argued that Lu’s success was a “public cultural phenomenon,” which represented “a new mechanism of star creation” in the digital era. “He emerges from big data,” Wu wrote in a 2015 column, quoting a marketing representative at search engine Baidu.

The “data” is deliberately engineered by fans. In fact, whether it was the Guinness Record or the viral mailbox, such stunts were elaborately (and unofficially) organized by Lu’s extremely disciplined fan club, who see it as a duty to hype up their idol. Working on sites like Baidu’s forums, and Weibo, these “Lu-fans” worked like a well-run army: voting on any award he was nominated for, organizing promotional activities on his behalf, and “monitoring public opinion, clarifying harmful rumors and burying negative comments” as efficiently as any state censor.

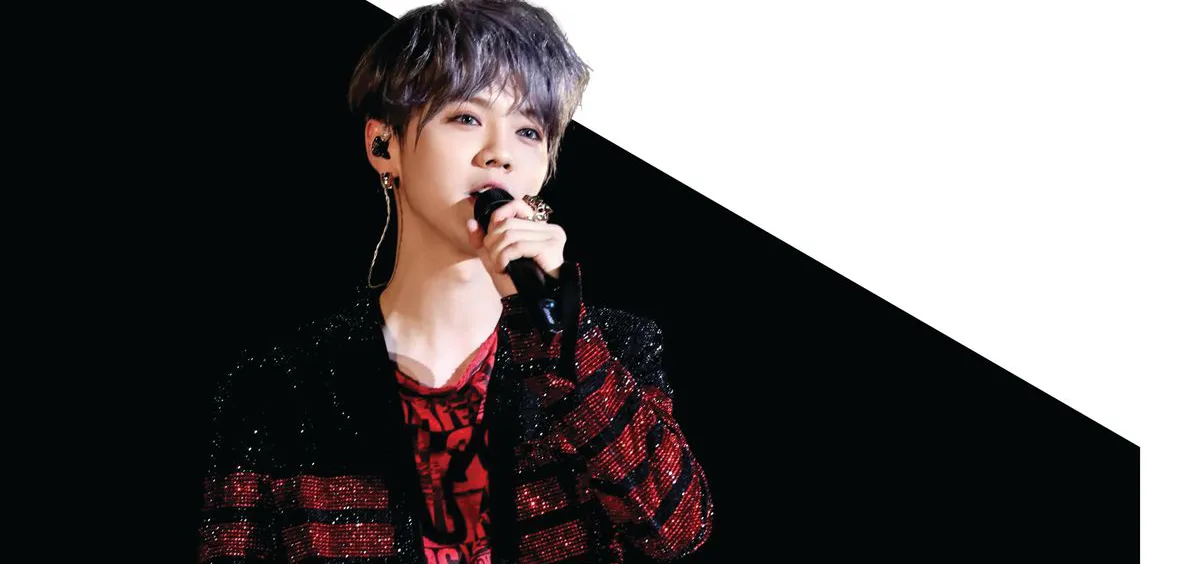

Lu Han taking photos with fans at a fan meeting in 2017

“‘Doing the data’ is a common practice among fan circles,” Qiqi explains. “It’s the most effective and feasible way to support your hero. Today, internet traffic is about competitiveness, representing a star’s influence and commercial value.”

Xiao Yao, who has taken part in such campaigns before, says that, sometimes, Lu would acknowledge fans’ efforts by showing up at their activities and sharing photos. For the fans, “It felt like he understands everything you do for him. Though he is not sentimental, he ‘spoils’ his fans.”

So when Lu chose to announce his romance, pampered fans couldn’t take such a heavy blow. By the following month, according to AIMan Data, Lu lost about 800,000 active fans, and some even became “haters.” A Lu Han status update early last October, before news of his girlfriend, could prompt more than 29,000 comments. On the same day a year later, when Lu published a post promoting his concert in Beijing, there were only 10,000 responses.

“A real fan wouldn’t leave him for this,” opines Qiqi. “I think those were just ‘girlfriend fans’”—that is, devotees who fantasize themselves in the role of Lu’s true love. Quoting Sakurai Sho, a member of Japanese boy band ARISH, Qiqi believes “‘being an idol is all about selling dreams.’ Lu Han wakened his fans from their dreams, so had to pay a price.”

Even if Lu had been more-or-less prepared for losing some fans—teens and tweens grow up, after all—he may not have not anticipated that a new generation of idols would rise overnight to rob him of more. In January, talent show Idol Producer hit screens and soon introduced dozens of new “traffic stars” to the market. By May, findings from AIMan Data showed that Cai Xukun, a 20-year-old who debuted on the show, had ended Lu’s months-long reign as China’s most-discussed star. Another report in June alleged that around 9 percent of ex-Lu fans had become Cai followers.

The sponsors soon responded: Mobile phone brand Vivo, which had chosen Lu to be their spokesperson in 2017, invited Cai to co-endorse their new product with Lu in 2018.

“[Traffic stars] are mirages built up by empty enthusiasm, dolls inflated by internet power,” writer and critic Han Songluo declared on Weibo in October. “This power can easily take them as a puppet, only using their face and a signified personality. But it is also merciless, only lasting for three years at most.”

To make things worse, even if the “Lu Han effect” works among his own fans, the general climate is becoming less and less friendly to “traffic stars”: new release Europe Raider, starring Kris Wu, another former member of EXO, current Rap of China judge, and aspiring rapper, made a miserable 150 million RMB at the box office; TV drama Martial Universe, starring another “fresh meat,” Yang Yang, received a record-low audience rating on Dragon TV; top traffic actress Yang Mi tried serious acting in Baby, a 2018 weepie about child abandonment, but the movie earned only 20 million RMB at the box office and a rating of 5.5 on film-review app Douban…the list goes on.

“Transition is a problem every traffic star has to face,” Xiao Yao believes. “If they can’t make some achievements and gain recognition from the public, they will become washed up.”

Qiqi agrees: “Popularity is seasonal. No one can live on traffic forever. The only way to survive is to create good products.”

For now, Lu himself seems neither as worried as his fans, nor concerned with the criticism. “It’s impossible to ask those busy ‘little fresh meat’ or ‘traffic stars’ to create perfect roles now. They have no time,” he told Southern Weekend in May. “I never considered producing any ‘masterpiece’ in the first place, because it’s too difficult.”

The Han Over? is a story from our issue, “Home Bound.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.