Review of Feng Xiaogang’s newest film

The villains in Feng Xiaogang’s latest film, I Am Not Madame Bovary, are not malevolent; their worst trait is cowardice mixed with fawning stupidity. None dare contradict officials higher up on the food chain and this fear drives them to interfere even when they are told it’s unnecessary.

As this insecurity spreads like a virus, so too does chaos, thus fuelling the plot, which starts with a minor divorce case and snowballs. Dozens of officials (and no doubt hundreds off-screen) are caught in its web.

The film’s title is a reference to an ancient Chinese novel, but something is lost in the English translation. There is no reference to Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary here; In Chinese, the title is “I am not Pan Jinlian.” An approximate historical character was chosen for the English translation, Pan Jinlian being an fictional adulteress whose very name is a byword for promiscuity and deceit, and Emma Bovary is, as they say, chabuduo (差不多, close enough).

The protagonist of the film, Li Xuelian (played by Fan Bingbing, who looks much less glamorous than usual) is outraged that her husband violated a divorce agreement. The couple was supposed to get divorced in order to get an extra apartment and some work benefits (employees in China occasionally receive an apartment from employers, but just one per married couple), but once the “fake” divorce was finalized, he decided that it was real. With the divorce done and dusted, there was nobody she could turn to, so she starts moving up the chain of authority in pursuit of justice. When her ex-husband accuses her of being Pan Jinlian, her outrage is kicked up several notches, prompting her to utter the title words, “I am not Pan Jinlian!”

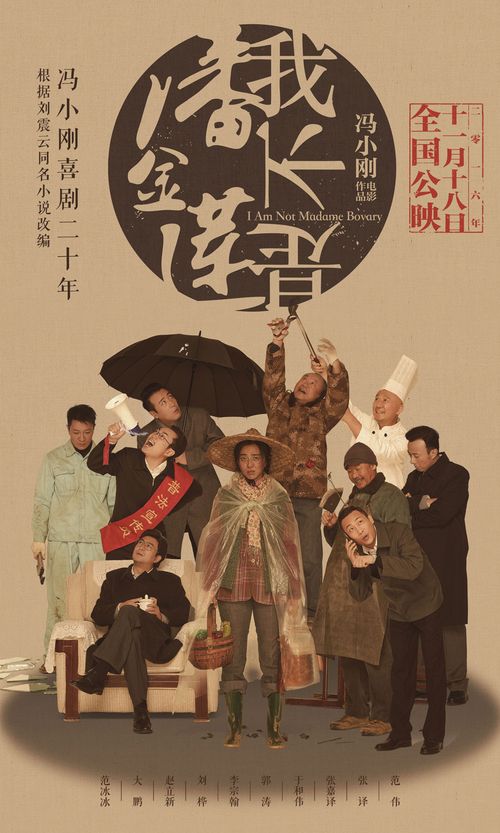

Li Xuelian doggedly pursues justice throughout the film (Image from I Am Not Madame Bovary via Douban)

Li is a difficult character to empathize with, as much of the film’s action is derived from her stubbornness. A final revelation goes a long way toward humanizing her, but she still remains a figure who demands understanding for her own misfortunes while turning a blind eye to the suffering she inflicts upon others. This isn’t necessarily a stumbling block for the film. While it excoriates the officials who spend more time mouthing platitudes than they do helping the people, a key theme is also the magnitude of the task they face. At what point is it reasonable for them to simply say “I can’t help you?” And to what extent will the system let them do so?

The filmmakers employ some interesting techniques; scenes in Li’s backwater hometown are seen though a black circle as if looking through a telescope.Then, when she makes her way to the big city, this gives way to the full screen, demonstrating how small and closed off her world really was. As her vistas are opened up, so too are those of the viewers, quite literally.

Feng Xiaogang contrasts rural life with attempts at justice in the big city (Image from I Am Not Madame Bovary via Douban)

In the end, the film highlights the unreasonableness of both sides; Li’s unrealistic expectations are contrasted against the well-meaning but incompetent and interfering officials. Audience members are left to decide whom they sympathize with more. While this may have been a necessary contrast for the film to get approved and become the success that it has, it’s also what prevents the movie from taking any powerful stand one way or the other, or really delivering any strong messages with impact. The film’s denouement offers some catharsis as to Li’s motivations, but little else by way of closure.

Movie Quotes

Zheng Zhong: So, for officials like us, this peasant woman commands our fate?

Nà gèjí língdǎo, jiù bèi zhège nóngcūn fùnǚ ná zhù mìngmén le?

那各级领导,就被这个农村妇女拿住命门了?

Wang Gongdao: Stopping Li Xuelian is no less important than firefighting.

Fáng Lǐ Xuělián, bùbǐ fánghuǒ zérèn xiǎo.

防李雪莲,不比防火责任小。

Wang Gongdao: If she were one person, it would be easy. But now, she’s become three people. To us, she’s a tenacious pest, her ex-husband said she’s a Pan Jinlian; she thinks she’s a victim of injustice. She trains like Lady White Snake, ten years of complaining. She’s a master at it.

Tā yàoshi yīgè rén dào hái hǎoshuō, guānjiàn shì tā xiànzài yǐjīng biànchéng sān gè rén le. Wǒmen juéde tā shì xiǎo báicài, tā qiánfū shuō tā shì Pān Jīnlián, tā zìjǐ juéde zìjǐ yuān de xiàng dòu é. Tā yòu xiàng gè bái niang zi yīyàng zài nà’er xiūliàn, yī gào jiùshì shí nián, dōu gàochéng jīng le.

她要是一个人倒还好说,关键是她现在已经变成三个人了。 我们觉得她是小白菜, 她前夫说她是潘金莲, 她自己觉得自己冤得像窦娥。她又像个白娘子一样在那儿修炼, 一告就是十年, 都告成精了。

Zheng Zhong: She’s got your number. Let me meet this Pan Jinlian.

Tā bǎ nǐ bī dào zhège fènr shàng, nà wǒ jiù huì yī huǐ zhège Pān Jīnlián.

她把你逼到这个份儿上,那我就会一会这个潘金莲。

I Am Not Madame Bovary is a story from our issue, “Taobao Town.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.