Three of the greatest influences on Chinese cookery

Chili peppers were first recorded in China in the writings of a Hangzhou scholar, Gao Lian, in 1591: “It is pretty to look at.” Terse, but accurate. Strange as it may seem, Hangzhou, a city of trade, used chili peppers as decoration rather than seasoning.

Over 400 years later, the chili can be found in cuisines from Sichuan to Hunan, featuring a variety of pungent aromas and an occasionally masochistic amount of spice. Yet miraculously, Hangzhou, as the importer of this plant, is one of the few to eschew this spice in favor of its own culinary traditions.

First-timers to Hangzhou often think at first that the food is a bit bland. Rather than concentrating on the overly-seasoned diet, Hangzhou cuisine places an emphasis on qualities such as freshness, natural flavors, and respect for the food’s unique texture.

The reason Hangzhou food lacks the seasoned blitz of other Chinese staples is simple; it’s the legacy of the cultured class of pre-modern China. The famous attitudes of the elites of Hangzhou can be found in the dishes: a gentle spirit, a Confucius-centered nobility, and a penchant for delicate flavors.

The poets and scholars that seemed to gravitate to Hangzhou naturally became the city’s food critics. A list of China’s great foodies of the past include Su Shi, Li Yu (李渔), Lin Hong (林洪), and Yuan Mei—each with a canonical recipe book under their name that is still cherished by modern Chinese cooks. Every one of them cultivated their taste buds in Hangzhou.

Although they lived in different times, these great poet-cooks shared many of the same values on food as the foodies of today. They studied natural flavor and texture, used restraint in seasoning, abstained from lavishness in presentation, and they even rejected cruel farming techniques. The local cuisine of Hangzhou is identified by the careful, delicate art of making food with the care of a poet.

Su Shi and Pork

Su Shi, the respected 11th century poet and Hangzhou governor, more popularly known for his pen name Dongpo Jushi (东坡居士), is the inventor of the ubiquitous “Dongpo” pork (东坡肉) dish.

Dongpo pork involves pan-frying a chunk of pork belly with a fatty layer. It is then boiled on low heat with soy sauce, sugar, fermented bean paste, and Shaoxing wine until it is tender, almost falling apart. Su Shi, a lover of pork, even wrote a poem on cooking pork: “Mild is the fire, shallow is the water, give it time, and it will be divine.”

Literally meaning “Dongpo Meat”, the dish sounds a bit cannibalistic to some, and 600 years later food critic Li Yu was still making fun of this observation in the pork section of his own recipe book: “What had he done to feed his flesh to hungry people for hundreds of years? I know how to appreciate pork, but I do not dare to say a word about it for fear that I become the second Dongpo.”

Su himself later swore off meat after serving a prison sentence and thinking on trapped animals in cages. He wrote of jail, “I felt just like a fowl waiting in the kitchen…I can no longer bear to cause any living creature to suffer immeasurable fright and pain simply to please my palate.”

Less Meat, More Vegetables

Su Shi is not alone in his vegetarian preference. Lin Hong, a scholar of the 12th century who spent his prime years in a Hangzhou prison, was the author of Shanjia Qinggong (《山家清供》), a recipe book that mainly consisted of vegetarian dishes.

Li Yu, a script writer and opera theorist who lived between the Ming and Qing dynasties, was another strong vegetarian advocate. The first sentence of the “Meat” section of his recipe book is, “Meat eaters are base.” This, confusing as it is, is a quote from Confucius, and “meat eaters” in the original context meant rulers. Li expounded on the sage’s words in his own (not so reliable) way, “Meat eaters are base not because they eat meat but because they are short-sighted. The grease of the meat cools down to solid fat and chokes their chest and heart…Even though I’m writing a recipe for meat, I do advise all my readers: less meat is better.” Explaining why he prefers vegetables, Li wrote: “For one, I believe in living a frugal life; for another, we should love all kinds of life and be particularly careful with anything that involves killing.”

Beware the Mediocre Cook

Yuan Mei’s Suiyuan Shidan (《随园食单》) is perhaps the most widely-read ancient recipe book of its kind. Chefs and food critics are often accused of having eccentric dispositions, and, for his part, Yuan never minced words when discussing his most hated enemy: “the mediocre cook.”

“Each food has a flavor of its own, and you can’t mingle different flavors. I notice how mediocre cooks put chicken, duck, pork, and goose into one pot to stew…If these animals were aware of it, they would be petitioning for the chef’s punishment in hell,” Yuan wrote. “Mediocre cooks always keep a pot of pork oil, and finishing each dish with a spoonful, so as to make it greasy. Even the delicate bird’s nests are not spared from this humiliation. Those ignorant commoners…are the reincarnations of hungry ghosts.”

A depiction of Yuan Mei at the Chinese Hangzhou Cuisine Museum

Yuan’s definition of good food, which can still be found in most Hangzhou cuisine today, was balance: “Good food is rich and aromatic, but not greasy; fresh and natural, but not bland.”

As one might have guessed, Yuan Mei also emphasized dining with good manners. He also considered hot pot, then popularized as a court favorite, as a barbaric way to eat: “All that hustle and yelling around the table is distasteful.”

If that’s what Yuan Mei thought of hot pot, he would be very disappointed with modern China’s overdose of spices and peppers, which seem to purposefully override natural tastes and aromas. This purist attitude makes Hangzhou one of the few places where foodies can find fare that flaunts its flavor.

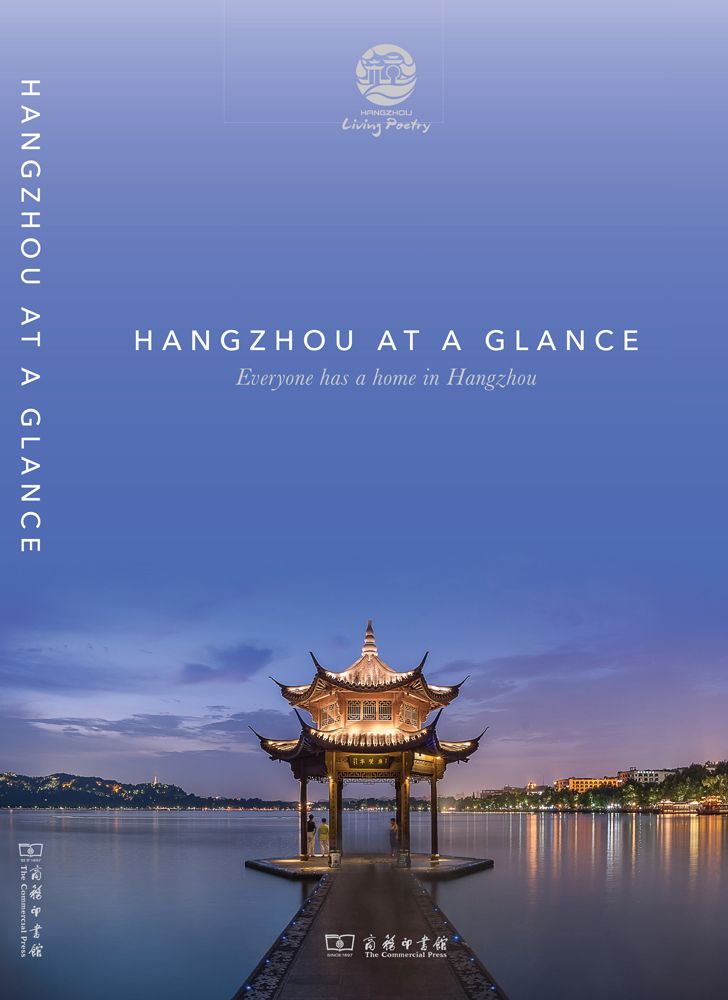

Cover image is of the Chinese Hangzhou Cuisine Museum

Excerpt taken from Hangzhou At A Glance by TWOC. You can pick up a digital copy on our China Dispatch app. Go get your copy now.