China’s status as malware haven has a risky message for all

It’s usually a young woman, moving through the subway from person to person. Politely, she asks if commuters would like to sign up to her WeChat account. In this case, she explains it’s a small fashion boutique which will provide updates on the latest products, chosen herself, as part of her small business aspirations, with the updates sent to their smartphone via her WeChat feed. Most passengers wave her away. While at first glance her entreaty seems harmless enough and the personal nature of the advertising makes it seem friendlier than signing up to a mass-email newsletter, these Beijing commuters are generally wary of unsolicited approaches.

A few may have read headlines that shed light on how the personal touch can sometimes make these accounts shadier than their “official account” counterparts. When the boutique operator gets a new WeChat contact, that person’s account information becomes visible and is worth money to advertisers who pay in bulk for WeChat accounts they can spam with offers.

The boutique operator is likely just turning a buck with her clothes, but if she sells those WeChat IDs to third parties, she will, perhaps unwittingly, become yet another face of China’s electronic spam problem, and all those who signed up to her account could be in for some very risky friend requests.

SPAM MEETS MALWARE

Most people who buy SIM cards in China have been unfortunate victims of spam—often their contact number was sold to spammers by the SIM card manufacturer or an intermediary long before the SIM card was purchased, thus they are doomed to receive unwanted advertising right from the beginning.

But malware has taken advantage of spam’s natural, virus-like qualities.

The Conficker Worm is the world’s most common form of malware, according to internet security giant Check Point, but a new creepy-crawly from China recently buzzed into the top ten rankings.

Going by the name Hummingbad, Check Point’s report indicates it has made its way onto around 85 million devices worldwide, affecting ten million users (with 1.6 million users in China, 1.3 million in India, and over 286,000 in the US). Once on a device, it can create fake clicks on Google Play applications to install even more malware. However, as with the most common viruses, the goal is not to cripple the host; Hummingbad wants to spread spam, be it real or just a click mirage. Aside from delivering spam, it also defrauds ad networks (the large companies that pay-per-click to place adverts in apps made by small app developers). Essentially, Hummingbad tricks these ad network companies into thinking someone has clicked on an advert and thus should pay out the fraction of a cent that is owed. Generate enough fake clicks, and it adds up. Hummingbad is believed to generate around 300,000 USD per month.

Which, of course, raises the question: who is taking that cash?

Check Point lays the blame squarely at the feet of Yingmob, which it says is partly a legitimate advertising firm based in Beijing and partly made up of (possibly semi-autonomous) malware developers based in Chongqing, operating under the umbrella of the “Development Team for Overseas Platform”.

Hummingbad reportedly wasn’t Yingmob’s first attempt. Other internet security research companies have pointed the finger at Yingmob for creating Yispecter, one of the first pieces of malware able to target non-jail-broken iOS phones in a sophisticated fashion. A jail-broken phone is one with a system that has been seriously altered by its user so the company can no longer guarantee the settings work.

Yispecter’s modus operandi is a little different; it uses four mechanisms to infect phones, the most popular being via Kuaibo’s QVOD player, which it exploits to install malware. On a side note, the CEO of Kuaibo, Wang Xin, became an unlikely hero to horny Chinese netizens in January 2016 after being put on trial for spreading pornography due to his media player being all but synonymous with porn. He quixotically challenged the charges in court by boldly stating that Kuaibo was no guiltier than any search engine that has a lot of porn, i.e. all of them.

It didn’t work.

CHINA FIGHTS BACK

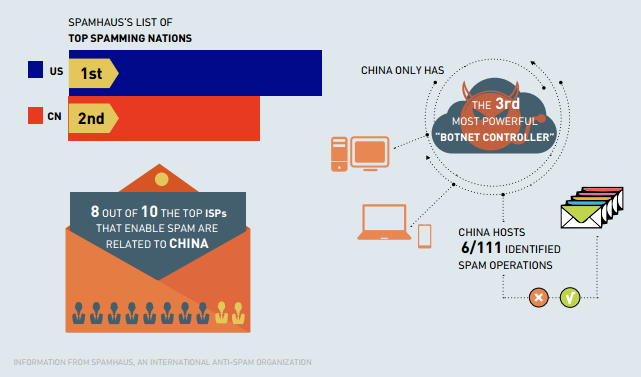

Now the number two spamproducing nation (behind the US), according to international spambusting group Spamhaus, China has been significantly stepping up its ground game in dealing with spam in recent years. Whether or not it can combat the tide being unleashed by technological advances is an open question, but Chinese anti-spam bodies do have significant wins to their name.

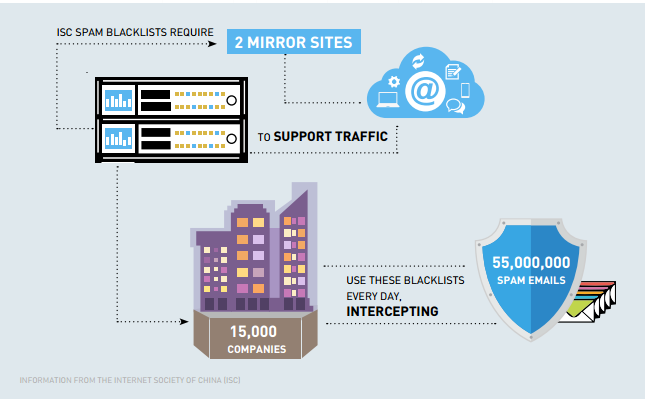

China has an Anti Spam Alliance which is run by the Internet Society of China (ISC). The ISC approach to dealing with spam is to target internet service providers (ISPs) that knowingly host spam. This, of course, can get a bit tricky, as it comes down to defining what is and isn’t spam.

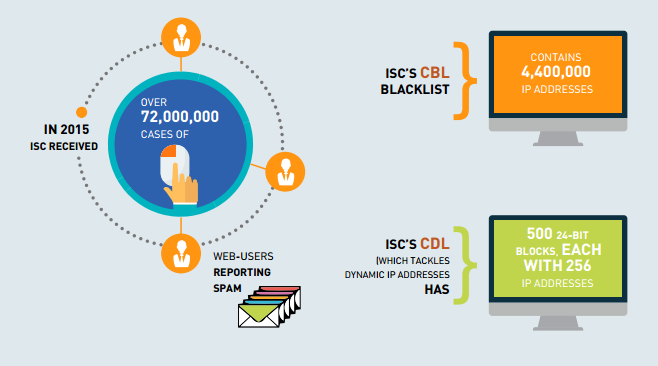

Before defining spam, they have to spot it. Li Jia, a representative from the ISC, told TWOC that much of this comes from reports from web users, but also international exchanges and “honey pots” where a web crawler has found an email address listed somewhere online and starts spamming it.

Deciding whether or not something qualifies as spam depends just as much on delivery method as content. Unsolicited bulk emails or targeting emails from anonymous senders are common ways to classify spam, though content that is deemed pornographic or “counter-revolutionary” can also get it blacklisted.

Li pointed out that the situation is getting better. “With the enforcement of the real-name cell phone registration system, the mechanisms to manage text message spam are improving. Despite problems with false base-station text messages and spam messages on iPhones, the overall antispamming situation looks a lot better than a couple of years ago,” he said.

“It is not efficient to just deal with email accounts of spammers, as it is so easy to spam from new accounts. Therefore, for email spam we usually blacklist the IP addresses of spammers,” he said. “China doesn’t have any official registration for IP addresses of mail servers, and thus lacks the regulation and management of undisciplined companies as potential spammers.”

Of course, with different systems for identifying spam, some very curious discrepancies will emerge.

Spamhaus, based in Germany, maintains a public list of ISPs that are repeat offenders, with many on their top ten being Chinese web addresses—the website of internet giant Tencent (responsible for making ubiquitous messenger app WeChat) clocks in at number five on the Spamhaus list, with DrPeng, a computer hardware retailer, coming in at number one. In fact, eight of their top ten spam-enabling IP addresses all either have a .cn or .hk address, or are recognizable Chinese companies. Spamhaus’s list, however, evaluates their spam abuse departments and their effectiveness, judging them on how well they responded to spam complaints, calling them “de-facto” spam havens, noting that the problem is that they take a “blind eye” to the spam they host, most likely due to the significant profits on offer. Thus, they are being judged on a lack of enforcement rather than creating the spam themselves.

“Click Click Boom” is a story from our issue “Gender Equality”. To read the whole piece, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.