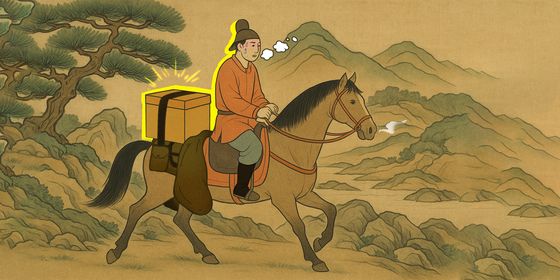

Playing second fiddle to the Monkey King does not do this man justice

Most Chinese are familiar with the Tang dynasty (618 – 907) monk Xuanzang (玄奘) through his portrayal in the classic Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) novel Journey to the West as a hapless and easily duped figure, perpetually in need of rescue by his disciple, the Monkey King. But that’s a harsh misconception of the man himself—a determined Buddhist monk who trekked from China to India nearly 1,500 years ago— who deserves to be recognized as one of China’s, if not the world’s, greatest ever wanderers.

He is not just a translator of Buddhist sutras who racked up a few miles on the job: in 19 years, Xuanzang covered an epic 250,000 kilometers across 110 countries and regions. He survived windswept deserts and snow-capped mountains, evaded bandits and murderous attacks, all the while scribbling down observations in his book, Great Tang Records on the Western Regions (《大唐西域记》).

At age 26, Xuanzang was already a well-known monk in Chang’an (now Xi’an), the capital of the newly founded Tang dynasty. Despite studying all available Buddhist sutras and visiting numerous monks nationwide, he still found the existing schools of Buddhism conflicting and confusing. He resolved to return to the source of the sutras themselves, India, in an attempt to straighten out the issues. Aside from his own journals, which focused mostly on geography, scholars now have to rely on Xuanzang’s disciples for details of his exploits. While it may be necessary to take some of their tales with a pinch of salt, there’s no doubting the sincerity and difficulty of his endeavors.

Learn more about the history of travel in China:

- A Trip in Time: How Did People Travel in Ancient China?

- 30 Years of Backpacking in Revolution and Leisure

- Learn the Chinese Character for Journeys and Adventures

Initially, Xuanzang’s toughest obstacle wasn’t the natural world, but the political one. The Tang dynasty was only three years old and mired in border disputes with the Eastern Turkic Khaganate. Tang residents at the time were forbidden to travel abroad without special permission, and Xuanzang’s request to Emperor Taizong fell on deaf ears.

Undeterred, he saddled up and headed west, traveling under cover of darkness and holing up in hidden refuges by day. Even after taking these precautions, he was still caught by an official in possession of a wanted poster bearing his description. Luckily, the official was a fellow Buddhist who had more respect for Xuanzang than the emperor’s edicts, and he allowed the monk to continue his venture to India.

The journey didn’t get any easier. Archers’ arrows and parching deserts further impeded Xuanzang’s progress before he reached China’s western border. A merchant who had offered to guide Xuanzang through the treacherous border fortress Yumen Pass twice threatened his life, fearing the monk would expose their attempted crossing.

In Gaochang, a prosperous country located near the site of modern-day Turpan in Xinjiang, Xuanzang was invited to dine with King Ju Wentai, who, impressed by the monk’s knowledge and fortitude, saddled him with supplies, servants, and tribute gifts to ensure easy passage.

Even with such backing, the group was totally unprepared for the perils of Lingshan Mountain. Xuanzang wrote, “The mountain is frozen in ice even in spring and summer, [and] a disaster known as the ‘furious dragon’ [avalanches] often occurs.” The constant snowstorms made it near impossible to cook, and after seven days only two-thirds of the weary group emerged alive on the other side of the mountain.

When Xuanzang finally reached India, he sailed down the Ganges River in splendor—only to be captured by bandits who intended to sacrifice him to the Hindu goddess Durga. Facing imminent death, the monk drifted into what he believed would be his final meditation. However, in a seemingly miraculous intervention, the bandits took a sudden storm as a divine sign, and they allowed the monk to live.

After more than four years since he set out, Xuanzang finally arrived at his destination, Nalanda, the center of Buddhism in India. He spent the next four years studying the Discourse on the Stages of Yogic Practice, the sutra that had drawn him to India in the first place. His services in ensuing years as a teacher and Buddhist debater were so in demand that two local kings almost went to war over who would have the honor of hosting his lectures.

When Xuanzang set off on his return journey to Chang’an in 643 AD, loaded with sutras, Buddhist statues, and Indian plant seeds, he was unsure if he’d be allowed back. He wrote a humble, carefully worded letter to Emperor Taizong, confessing the illegality of his travels and praising the emperor’s power to ensure he had been kept from harm. The emperor not only forgave his crime, but dispatched officials to meet him on the western border.

Xuanzang spent the rest of his life translating the sutras he had brought back with him. When he died in 664, a million people from Chang’an and other provinces attended his funeral. Emperor Gaozong, the son of Emperor Taizong, who could see Xuanzang’s tomb from his palace, was so saddened by this constant reminder of the monk’s death that he ordered it to be relocated to Bailuyuan, a mountain to the southeast of Chang’an, where it remains to this day.

Xuanzang’s Journeyer to the West is a story from our 2012 issue, “Adventure Junkies.” Support our magazine by becoming a subscriber!