The surprisingly delectable delights of “pock-faced woman” tofu

Sour, sweet, bitter, spicy, and salty make up the “五味” ( wǔwèi ), meaning the five basic flavors. Combinations of these flavors create culinary magic the world over, but sometimes obsession with a single flavor can have a unique charm. Sichuan cuisine, one of the eight major Chinese cuisines, enjoys a vaunted reputation both at home and abroad for its dedication to spiciness.

Let’s face it, most Sichuan cuisine involves a great deal of preparation and experience, but if you really want the authentic flavors of this famous cuisine in your kitchen, the best way to get it is with the legendary mapo tofu (麻婆豆腐).

Primarily based on Chengdu and Chongqing dishes, Sichuan cuisine emphasizes a refined selection of raw materials, proportions, presentation, and a sharp contrast of taste and color. It also features liberal use of chili peppers, Sichuan peppercorns, and ginger, so if you’re a fan of heavy flavors and have an urge to challenge your taste buds, Sichuan cuisine, and mapo tofu in particular, is the choice for you.

Tofu enjoys a history of over 2,000 years in China—high in protein and calcium but low in cholesterol and fat. Mapo tofu is essentially soft bean curd tofu set in a spicy chili and bean sauce. The sauce itself is typically a thin, oily, and red hot—often topped with minced meat. To describe authentic mapo tofu, you’ll need seven special characters: 麻 ( má , numbing), 辣 ( là , spicy), 烫 ( tàng , hot), 鲜 ( xiān , fresh), 嫩 ( nèn , tender), 香 ( xiāng, aromatic), and 酥 ( sū , flaky).

You can find mapo tofu in restaurants all over China, but it’s hard to get that authentic, Sichuan flavor just right, especially considering most adapt the recipe to their local area with the numbing and spiciness largely toned down. After all, not everyone can handle true Sichuan flavor.

The origin of mapo tofu can be traced to 1862 in the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911). A small restaurant called the Chen Xingsheng Restaurant near Wanfu Bridge in Chengdu was run by a couple surnamed Chen. Unpleasantly, the mapo in mapo tofu comes from the pock-marked face of Mrs. Chen—ma meaning pock and po meaning elderly woman. Oil porters crossing the bridge would use their own stock to save money, and ask the Chen restaurant to make them something nice.

Chen Mapo, as she came to be known, had her own unique way of cooking tofu—famous for its pleasant look, smell, and taste. In Chengdu Records, published in 1909, her restaurant’s name had changed to Chen Mapo Tofu Restaurant and was listed as one of the 23 most famous local restaurants in Chengdu in the late Qing Dynasty. Its flavor, cheap price, and pairing with rice made mapo tofu a Chinese food staple, spreading all over the country.

The best philosophy for mapo tofu is “the simpler, the better”. Even though the ingredients are cheap, the essence of mapo tofu lies in the skill; it is said that if you want to test a chef in Sichuan, just taste their mapo tofu.

Cut the tofu into even cubes of 1.5 cm. Firm tofu is ideal because it is easier to keep intact.

Add the tofu cubes to a wok of boiling water; boil for one or two minutes and then pick them out. Put them into cold water and set them aside.

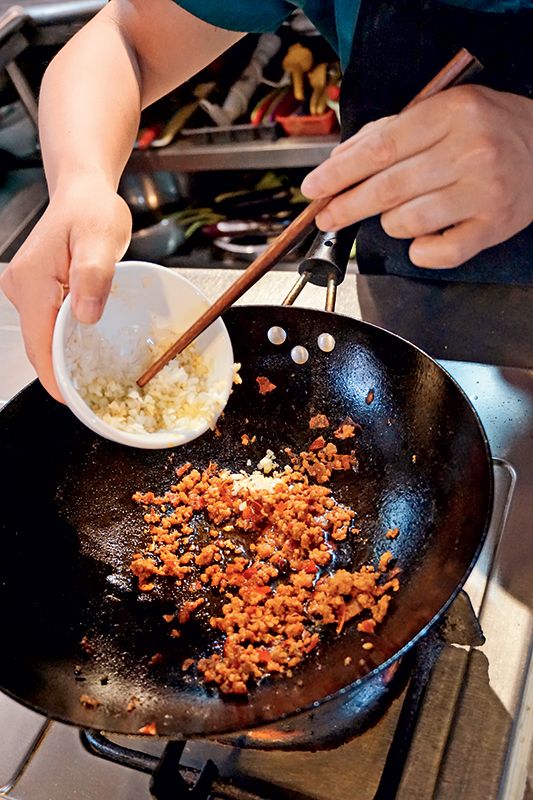

Pour out the water and place the wok over a high heat. Add cooking oil. When the oil is heated, fry Sichuan peppercorns for 10 seconds and then remove them. Add the chopped leek, ginger, garlic, and the minced meat. Stir-fry them together on a high heat until the meat becomes brown. Add the bean paste and soy sauce, stir-fry for another minute, add water as needed, and you now have your mapo sauce.

Drain the tofu cubes and pour them into the wok when the mapo sauce is boiling. Stir fry gently so that the tofu cubes don’t break apart. Add salt and white sugar to taste. Boil for about five minutes, and make sure to cover everything in the seasoned sauce.

Pour in dissolved cornstarch and stir well for 20 seconds until it becomes slightly sticky. Drizzle chili oil and sesame oil on the tofu. Then, transfer the tofu to a plate, sprinkle sliced spring onions over the dish, and enjoy.

Images and recipe provided with assistance from The Hutong cooking school.

“Mapo Tofu” is a story from our latest issue, “Law”. To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store or Google Play Store.