Buddhist chefs, husband and wife lung slices, and a very hungry ghost

As the train shot through one tunnel after another, with brief flashes of green valleys betwixt the fog, Beijing was left behind, and my destination, Chengdu, was in sight. It was, rather oddly, a burger that drove this trip, specifically a so-called “Chengdu burger”—plastered with a thick, salty layer of chili sauce so grotesquely saline that it destroyed any semblance of taste. As I shot back from the burger to see Beijing’s heavy, yellowish smog, I said to myself, “This is not life.” What’s more, it was life that made a mockery of Chengdu food. Beijing makes you hungry but often leaves you unsatisfied—a cornucopia of barely acceptable half-foods made ridiculous by regional interest. This bred in me the urge to volunteer at an obscure monastery called Guangyan Zen Monastery; this was not my first trip, but the hellish months that lead to the black dog of depression that is the Beijing winter urged me on to the slow-paced, strict life of the monastery to purge my body with a vegetarian diet, and most important of all, to regain my peace of mind.

After spending a decidedly chaotic 21 hours on a hard sleeper train, I arrived in Chengdu with the monastery just two and a half hours away—that is, if I set-off immediately from the long-distance bus station. However, as I stood under the sign at the train station, I inhaled deeply. Chengdu, after all, is China’s food capital, and it seemed a good idea to fill my stomach before purging my soul. Putting down my backpack in a hostel nearby, I headed directly to the oldest part of the city: Wenshu Monastery. Wenshu Monastery enshrines a piece of the scalp bone of Monk Xuanzang (玄奘), a personal hero of mine due to his wisdom as both traveler and translator. Also, it pays homage to Manjusri Bodhisattva, who provided guidance to many with his unsurpassed insight, including Sakyamuni.

However, the real draw is a well-known vegetarian restaurant. One odd thing about many Chinese vegetarian restaurants is that the major dishes on their menu are all “meat”—“chicken”, “pork”, “fish”, and even, in Chengdu at least, “rabbit”. They certainly look like meat—you can see the fat and the lean in the “pork” and the “fish” have scales; an inexperienced veggie might send it back or panic at the first bite. But, of course, these are largely tofu. While some might consider this hypocrisy, such ingenious imitations are well worth it.

An ancient corner of Wenshu Monastery in all its peaceful glory

However, I was distracted from this culinary counterfeit by an odd event; a library turned prayer hall hosted six paper men mounted on tall paper horses, guarding a gate, smiling into the distance. Their features and garments were all made with elaborate detail, in bones and strips of bamboo. An elderly lady told me, in Sichuan dialect: “They are mailers. They send messages to people on the other side. This morning we have already burned eight of them.”

This was three days before the Hungry Ghost Festival. In Beijing, shopping malls use various festivals for promotions and discounts, but this seems to be one they overlooked—the day on which one repents for their dead parents’ wrongdoings. The festival originates from the legend of Monk Mulian who found his mother in purgatory, her throat as narrow as a needle and starving. Mulian used his awesome powers to send food down her throat, but the food immediately turned to fire. At a loss, Mulian turned to Sakyamuni, who told him what could be done: monks in all directions prayed together. This became the origin of the rite of chaodu (超度, liberating souls from purgatory), and around the Hungry Ghost Festival people usually perform chaodu rites for their deceased parents. This rite was taking place inside the prayer hall, and the people chanting with the monks filled the entire courtyard.

A ritual for the Hungry Ghost Festival in Guangyan Monastery

But, as it happened, I was a bit of a hungry ghost after my long journey and ordered “husband and wife lung slices” (夫妻肺片) in a nearby restaurant, classic Chengdu cuisine. The somewhat cannibalistic literal translation describes a salad made from beef, skin, tongue, and stomach, all dressed in chili oil and white sesame. One explanation for the dish’s origins claims that a couple invented it by making use of ingredients discarded by Chengdu’s Muslim restaurants, with the character for “waste” (废) phonetically resembling the character for “lung” (肺). In one respect, all Chengdu food looks the same—be it dumplings, noodles, cold dishes or hot pot—everything is marinated in lashings of chili oil. As a result, a prevalent misunderstanding is that a dish is authentically Sichuanese as long as it is excessively spicy. However, you cannot judge food by sight alone. Aside from being spicy, authentic Sichuan flavors are very rich, depending on the way various spices and herbs are used, and every chef has a secret recipe. It is all at once spicy, sweet, numbing, and indescribably complex.

Missing the Guangyan Monastery’s closing time at five in the afternoon and not wanting to be locked out of its gate in the cold forest, I got off the bus halfway to Huaiyuan Town (怀远镇) to spend the night. The town had been an important center for governmental administration and local commerce in the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911) and prospered into a sizable town with 31 streets, containing temples, churches, and markets. In recent decades, the area’s relative poverty has kept its ancient beauty almost untouched. The town itself is now known for its bamboo handicrafts and two steam snacks, donggao (冻糕, literally “frozen cake”, made from rice and steamed in corn leaves) and yerba (叶儿粑, literally “cake in a leaf ”, a sticky rice bun with pork stuffing steamed in cedar leaves). And it is a reputation well earned. These snacks, available pretty much everywhere nowadays, are especially delectable in this odd, ancient town.

An elderly woman burning paper goblets for her deceased family members at sunset in Huaiyuan Town

Here, the alleyways often have distinct functions—an alleyway for butchers and fish-mongers, one for bamboo handicrafts, one for various spices and one for flour. Through these winding alleys, there is a restaurant street, where I treated myself to “hot pot noodles” (火锅面). The hostess explained this odd combination: “You cannot have hot pot in such a small town because it is too expensive for the locals. You can only have it in big cities like Chengdu, so we can only put hot pot soup in noodles.” The “soup” she mentioned, it turned out, was solid beef oil, stir-fried with a dozen herbs.

Night had begun to fall. The shops were shutting, and, strangely, everyone seemed to be piling up silver-colored, paper goblets in the shape of a pagoda. Then, they waited patiently for the sun to go down completely. When the dark finally fell, flames jumped high into the air, as people, young and old, stepped back from the fire, looking contemplatively as they remembered their departed family members. The whole town stood quiet.

The local bus took me to my next stop, Yuantong Town (元通镇), even smaller than Huaiyuan and even more laid back. The local economy subsists on the production of rapeseed oil, once used prevalently all over China until the 1990s when healthier cooking oils produced by large companies replaced it. Private rapeseed oil workshops quickly died out across the country, but the oil remains the first choice for Sichuan people as it has a particular smell that pairs perfectly with the local spices. Most of the workshops in Yuantong were run by families. The men and the youngsters in the family were engaged in the pressing process, while the elderly used shovels to further smash the seed grounds and sell them as fertilizer.

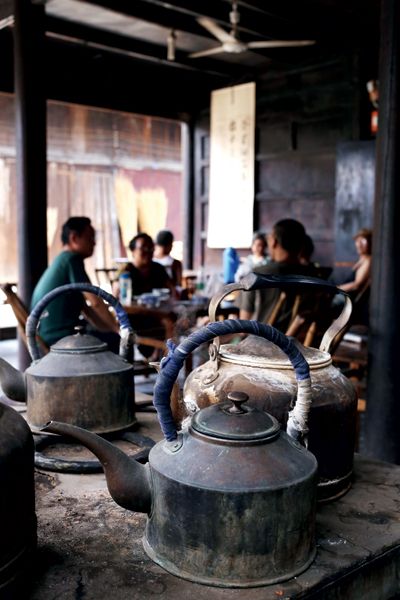

Craving some tea, I stopped at the Xia Family’s Ancient Teahouse by the river. Tastefully arranged with calligraphy writing, old-fashioned ceiling fans, rows of iron pots sizzling on coal stoves, and an actual well in the center of the room, the teahouse was a perfect spot to get my tea fix. The middle-aged Mr. Xia didn’t wear a shirt and was very proud of inheriting the teahouse from his father. “Take your time to drink,” he ordered bossily while pouring boiling water into my cup, even though it was still full. “We’ve lived here for over 100 years, and this well is older. You don’t get water this good anywhere. Whatever expensive tea you’ve had, our tea is better!”

Steamed snacks in the serene, peaceful town of Jiezi

Taking a three-kuai minibus bursting with teenager workers, I finally made it to Jiezi Town (街子镇). It is the wealthiest and newest town in the area. You can find a vintage shop selling old wood carvings in an alleyway where the shop owner explains, in great detail, the intricately carved and often gilded carvings taken from residences demolished during the town’s renovation.

Amongst the souvenirs, a strong aroma attracted me to a shop selling fermented bean sauce or douchi (豆豉), an ingredient often used in stir-fried dishes. An old man in a white undershirt told me that he had been a customer for over ten years. I couldn’t resist joining the queue and bought a jar of it, but it turned out to be a rather bad idea; the sauce had a strong smell, reminiscent of stewed meat.

A van with a local driver took me up the winding mountain behind Jiezi Town. While the thick green forest swung by the windows at incredible speed, the man still made time to yell a greeting to everyone he knew along the way. After 20 minutes, I arrived at my destination, Guangyan Monastery.

Surrounded by tall, straight cedars planted by monks hundreds of years ago, the monastery’s scarlet walls look serene and solitary. It is said that the monastery has a mystical power to induce people to leave the world behind, and one of the most famous monks in its history is Master Wukong (悟空祖师), the uncle of the Yuan Dynasty’s (1271-1368) first emperor. After his death, his body sat in a stupa by the main prayer hall until it was destroyed in 1951. The main prayer hall, however, survived the catastrophe and later the Cultural Revolution as it was turned into a pharmacy. The monastery usually only hosts a few visitors, but it was somewhat crowded due to the monks performing chaodu rites every day.

The monk receiving me was Master Xutong. He recorded my ID number and pointed to a notice on the wall for me to sign, saying the temple was, “a check-point of flowing population”—the result of recent incidents in Xinjiang. Master Xutong had not spoken a word for eight years, because he is practicing zhiyu (止语, literally “to cease speaking”), a Buddhist practice for one to obtain enlightenment via a vow of silence. I never figured out why the monastery put a silent monk in charge of guests. Master Xutong works hard on reading sutras; it looks like the thinking pains him, and he looks paler, thinner, and more wrinkled about the forehead with each passing year.

Master Xutong was also the only monk who could resist the dinners made by Master Zeng, the chef, as he strictly follows the rule that no food should be eaten after one in the afternoon. Despite being Cantonese, Master Zeng quickly grasped the gist of Sichuanese cuisine and has become famous for it. He is short, skinny, and dark, with childlike eyes, speaking broken Mandarin with a Cantonese accent. He is the loudest and happiest man in the monastery. I greeted him and congratulated him on his new, white, and now perfectly aligned teeth; the last time I saw him his teeth were almost all rotten. He smiled uneasily, nodded, and simply turned away. For a while I thought the old man had forgotten me, but after a few minutes, he suddenly threw a towel on the kitchen desk with a thump and said in his loud Cantonese accent: “Brother Huang, why didn’t you tell me that you were coming back?”

My work at the monastery was to clean the kitchen, which just happened to be after a massive renovation, so there was a lot of mess. The kitchen used to burn wood for heating, but last year the monastery received a large donation, which they spent on giving the kitchen a gas stove and a new row of stainless steel sinks. Obviously, the monks here take cooking very seriously, and Master Zeng, as a chef of high self-respect, prefers to keep it immaculate. Larger, wealthier monasteries often have opulent kitchens they ignore and let rot—perhaps indicating their piety and simplicity, but more likely mere neglect.

The Hungry Ghost Festival took place the next day, and Master Zeng’s kitchen was already preparing the ingredients: bamboo shoots freshly picked from the forest, tofu rolls, mushrooms, lotus roots, and various green vegetables. This is called the Arhat feast (罗汉斋), a special dish for the first and the 15th of every lunar month. It is named after the 18 Arhats (Buddha’s enlightened disciples) and dates back to the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Traditionally, it should consist of no more or less than 18 types of vegetables, but Master Zeng ignores this rule and just throws in whatever he thinks good for the stew. On an Arhat feast day, even the most pious monks, sworn to a life of self-denial, poked their heads in the kitchen to check on the progress once in awhile. By the time we sat down for dinner, the hungry ghost in all of us had definitely found salvation.