The dark world of online gaming

On July 22, 2013, police in Zaozhuang, Shandong Province, got an emergency call about an injured woman at a cosmetics store. When they arrived, they found a horrifying scene: a 24-year-old woman surnamed Zhao lying on the ground, virtually naked and covered in blood. She was alive when police arrived, but her injuries were so severe that she died shortly after paramedics rushed her to a local hospital.

It was a grisly murder, to be sure, but the case would not have made headlines across China were it not for the motivations of Zhao’s killer, a 20-year-old man surnamed Sun. Sun lived at home with his parents, who insisted that he get a job to help support the family. But, Sun was also deeply addicted to playing online games, so each day he would leave home as if heading to a job but instead headed directly to an internet cafe to play games. At around quitting time, he would return home. For a time, his parents were none the wiser, but since Sun needed money coming in—both to support his gaming habit and to convince his parents that he really was working during the day—it couldn’t last long. Actually getting a job would have cut into his gaming time, so instead, Sun tried to borrow from friends. When none would lend to him, he came up with another plan: robbery.

Looking for a place to target, Sun checked out Ms. Zhao’s cosmetics store on the morning of July 22. Finding it to be relatively isolated and under-staffed (Zhao was the only one inside), he found a hoe, walked into the store, and started smashing Zhao in the head. When he fell, he removed some of her clothes in a bafflingly misguided attempt to make the crime look like a rape (forensic evidence later proved it wasn’t) and then ran off with the cash he found in the register: 450 RMB.

Police found Sun quickly—he appeared pacing outside the store the morning of the murder on several security cameras—and he is now in prison. But his case and dozens of others like it are touted in the Chinese press as grisly evidence of one of China’s most serious problems: internet addiction.

Addiction By the Numbers

The story of Ms. Zhao’s murder is extreme, to be sure, but the young man’s desire to spend all day online playing games certainly isn’t. Internet addiction is taken seriously in the Middle Kingdom; China was the first country to label internet addiction a clinical medical disorder, and it has been a hot-button topic in the country for years. It’s a problem that, unsurprisingly, primarily affects young people. But, you might be surprised to learn that, of China’s approximately 40 million young internet users, some estimates suggest that as many as four million are addicted. And some go even higher. In 2007, China’s Communist Youth League suggested it could be as high as 17 percent of China’s young web users, or about seven million.

Those numbers are virtually impossible to verify, of course, but by all accounts the rates of internet addiction in China seem to be higher than corresponding rates in the West.

The reasons for the discrepancy are difficult to be sure of, but there are several key differences between the way that Chinese and Western children consume online games and the web in general that may help to account for the differing addiction rates.

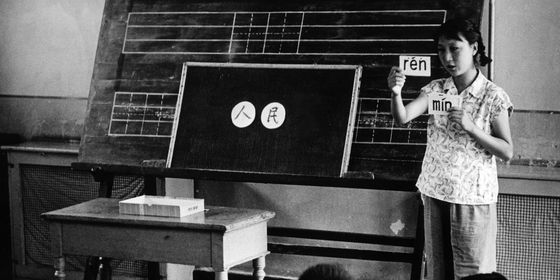

Internet cafes are places children can go to get their online gaming fix free from parental supervision, something many suggest is at the heart of China’s internet addiction problem in youngsters

First, Chinese children tend to access the web and online games at internet cafes. Even today, many Chinese families do not have a desktop PC, laptop, or internet connection at home, so kids who want their gaming fix need to go elsewhere. There are regulations that restrict minors’ access to internet cafes, but they are rarely enforced, and in practice many children are able to spend as much time in internet cafes as they want or can afford. There they are surrounded by peers and older gamers engaging in marathon gaming sessions, with precious little supervision. Where an American child, for example, is likely going to be doing most of their gaming at home where the parents can keep an eye on their child’s habits and limit online time if needed, many Chinese children play away from the prying eyes of their parents, who often think they’re at school or studying with friends.

School may be another major reason Internet cafes are places children can go to get their online gaming fix free from parental supervision, something many suggest is at the heart of China’s internet addiction problem in youngsters China’s youth seem to be more susceptible to internet addiction. China’s high-pressure education system can saddle teenagers with a lot of stress, especially when they’re a family’s onlychild. Visiting the internet cafe to play games is a cheap and convenient way to blow off steam, and it’s one of the only recreational outlets available to many Chinese kids around the clock. Western teens may blow off steam doing things like playing sports or playing in a band, but many Chinese kids don’t have access to the facilities for those sorts of activities. When the academic pressure gets to be too much, internet cafes and online games are a universally available and affordable release valve.

Another significant factor is the nature of the games themselves. There are, of course, thousands upon thousands of online games available in China, but the vast majority of them are free-to-play games. That means that instead of paying a lump sum upfront to “own” a game the way many Western gamers do, Chinese gamers pay nothing up front but are often enticed to make smaller in-game purchases like skins, weapons, and armor that fund the continued operation of the game. These free-to-play games, paradoxically, can be astronomically expensive when players look to collect everything that’s available for sale: the prices of single items are often low, but they add up quickly.

The free-to-play monetization system gives Chinese gamers an easy gateway into the game they want, and it can also easily lead players toward a sort of psychological trap. Unlike pay-up-front games, where the amount you’ve spent on the game has no further bearing on your experience, money spent on free-to-play games can make them feel like an investment. The more you spend, the more you feel you ought to play the game to justify having spent so much. And in many Chinese games, how much you spend also affects how much fun you can have; the baseline game might be free, but if you want to compete with the game’s top players, you’ll need to sink hundreds of hours into the game, and hundreds of dollars into buying the right equipment.

Moreover, free-to-play games are painstakingly crafted by their developers to keep gamers coming back again and again. The more time players spend in a game, the more likely they are to spend money on it, and without players spending money on in-game items, a free-to-play game will collapse rather quickly, so games are carefully designed and tested to make sure that the in-game systems keep players hooked—and, by extension, spending.

Finally, China’s game preferences themselves seem more likely to lead to addiction. Where Western gamers spend money on first-person shooters and sports games—games that focus on relatively short bursts of intense action—massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) are more popular in China. These games require hundreds or even thousands of hours to complete (if they can be completed at all), and have progression systems that make them relatively slow. Players are always grinding towards the next level, the next item, or the next skill unlock, but actually getting there could take hours, days, or even weeks. And of course, as soon as one such goal is achieved, a new goal presents itself. In other words, China’s gamers may be more addicted than gamers in the West, but that’s mostly because the deck is rigged against them. They’re playing more games designed to get them addicted, and they’re playing them in places where adults can’t supervise and intervene when they see a problem developing.

Stay tuned to see how Internet addictions are treated in Internet Internment Part II.