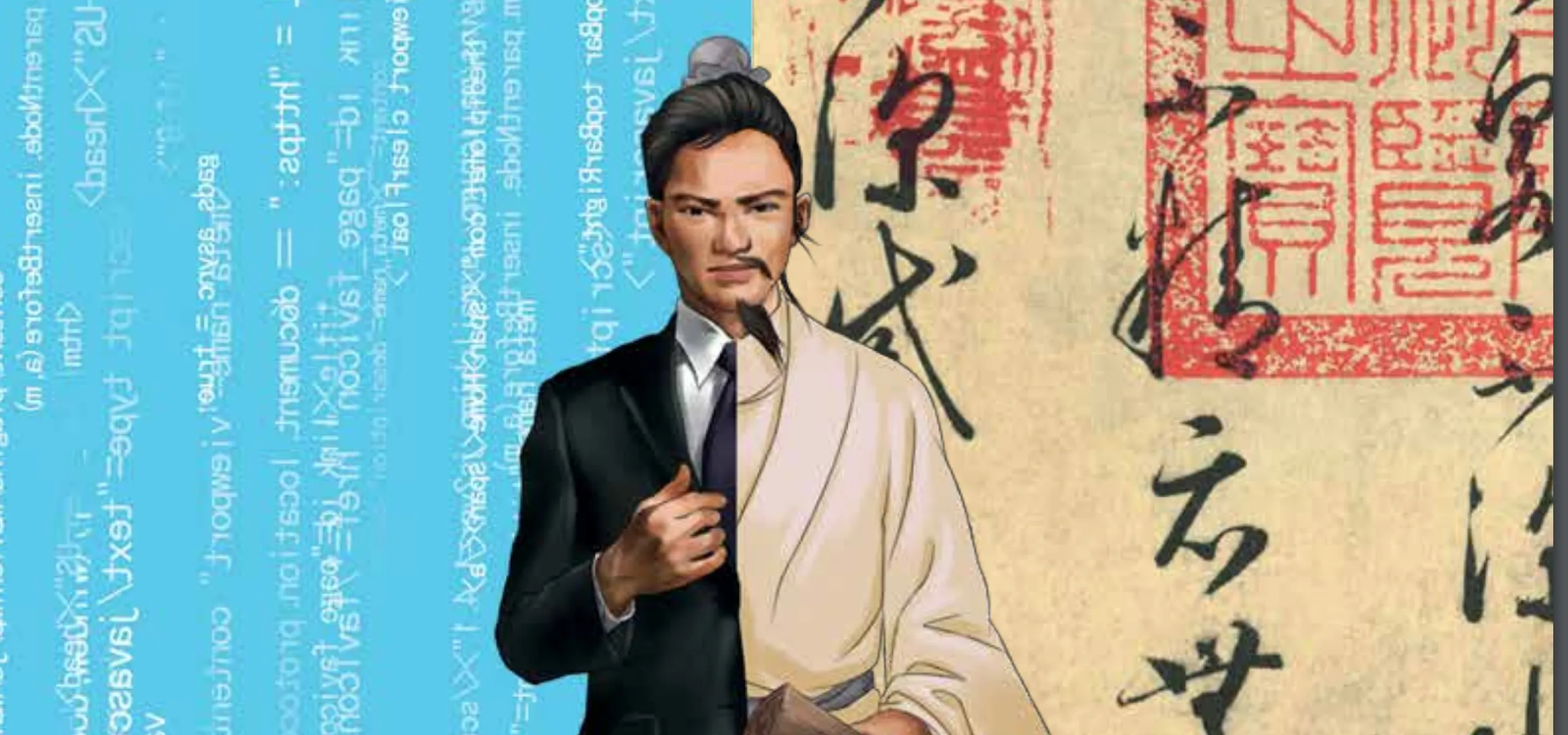

Parents are increasingly looking to ancient Chinese education to prepare their children for the modern world

In a time when China’s best and brightest furiously scramble to become world leaders in any available discipline, from IT and lasers right through to space exploration and robotics, there’s one area where the nation lays clear claim to being ahead of the rest—Chinese National Studies, or guoxue (国学). Naturally, throwing off its competitors through definition alone, the subject exists as an oppositional force to “Western” disciplines and, more often than not, refers to any field of scholarship that is traditional and native to China, be it Confucianism, Daoism, historical writings, ancient poems, medicine, or any number of the arts.

In a sense we could call this study, Sinology. However, whereas Sinology has primarily been underpinned by the outsider looking in—the somewhat fetishized “Western” gaze, which Edward Said famously termed Orientalism—as far as Chinese National Studies goes, the fascination comes from within. “Anything that has withstood the test of centuries and has been passed down today, as long as it has a positive effect in our society, that can be called guoxue—our unique traditional culture,” says Ji Jiezheng, a dignified woman in her 50s wearing, quite fittingly, a dark green qipao and a pearl necklace.

Currently holding 100 students, mostly between four and six years of age, Director Ji’s Chengxian Guoxue Institute is an example of the rejuvenation of guoxue in recent years, its popularity spiking quickly as an academic discipline. Affiliated with the respected Beijing Confucius Temple and Imperial College Museum (北京孔庙和国子监博物馆), the institute is proud of its work in enlightening the young through offering courses including introductory Confucianism, calligraphy, Chinese painting, and various traditional handicrafts for children.

Built in the 14th century under the reign of emperor Chengzong of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty (1206 – 1368), the construction of the Beijing Confucius Temple was an attempt by the emperor to steady rule over his largely Han subjects. Located just inside Beijing’s Second Ring Road, the temple has long been a place where emperors and scholars pay respect to the most influential thinkers in Chinese history, and it has continued regardless of the capricious rise and fall of any number of dynasties. It still receives considerable worship even today: every morning, a group of small children—girls in pink and boys in blue hanfu (the traditional robes of the Han people)—line up and pay four respectful bows to a marble statue of Confucius, before starting their day at the institute.

In a world that’s obsessed with piano, Olympic-level math, and Disney-inspired English, it seems to many that traditional culture has emerged as a key element missing in a modern child’s development. “The ideal life pattern of us Chinese is to first cultivate the moral self, regulate one’s family, then go on to attend state affairs, and finally bring world peace,” Ji says, quoting the Great Learning (《大学》), a bona fide Confucian classic, adding her own flavor with: “No matter what career the kids pursue in the future, they first have to learn how to be a moral person.”

“Chengxian” means “to become a virtuous person,” which is also part and parcel of Confucian beliefs. “As society developed, Chinese families shirked [their responsibility] and the human element seemed to diminish gradually. We no longer pay attention to manners and courtesy as before,” says Ji, who believes traditional etiquette helps form the bedrock of what it means to be a good person. As such, the institute puts Di Zi Gui (《弟子规》, literally “Standards for Being a Good Pupil and Child”) at the center of its teaching and philosophy. Di Zi Gui is merely a thousand-word long list of rules and suggestions written in the Qing Dynasty (1616 – 1911) by scholar Li Yuxiu, based on his teaching experience of Confucianism to young children.

In it, a good child is held up as a respectful, moral, and harmonious member of a family and community, as one excerpt goes: “Elder siblings should take care of the young, and the young should respect their elder siblings. The harmonious relationship among siblings will please the parents, thus filial piety is achieved. Don’t take wealth too seriously, and you will be free from resentment; be tolerant in your words, and conflict will dissolve naturally.” To the institute, Di Zi Gui is not just a collection of practical advice, but answers a few of the ultimate philosophical questions. “It guides you to discover who you are and what you are supposed to do at your present stage of life,” says Ji.

It’s not just private guoxue institutes such as Chengxian that are promoting this philosophy; prestigious universities such as Tsinghua and Peking have also established research centers that firmly reside within a Confucian embrace. Wuhan University even goes so far as to offer a PhD degree in guoxue, which produced its very first Doctor of Guoxue in 2012. In the recent upsurge no one seems to quite remember that, less than 50 years ago, Confucian classics and traditional etiquette were despised by the cultural reformists and were intensely vilified as an outdated, corrupt, poisonous, and negative force, and, as a result, such teachings were hunted down and exterminated with careless abandon.

Modern wrangling aside, guoxue has always occupied a special place in the hearts of Chinese intellectuals. During the 19th century, during the clash between China and the outside world, teachings from the West were labeled “new studies” while the original disciplines became known as “old studies”, or guoxue. Advocacy of guoxue’s continued ascendancy is ever-present, especially with the rise of the “Masters of National Studies” such as Zhang Taiyan (章太炎), Chen Yinke (陈寅恪), Qian Mu (钱穆), and most recently paleographer, linguist, and writer, Ji Xianlin (季羡林).

The original academic definition of guoxue was much narrower than its popular understanding today. According to Zhang Taiyan’s famed lectures on guoxue in 1922, the subject can be divided into three schools: the study of jing (经学), made up of the Confucian classics; the study of philosophy, which are schools of ancient Chinese philosophy outside Confucianism; and the study of ancient literature. Ji Xianlin, on the other hand, proposed the concept of a “broad guoxue” (大国学) in 2008, in which he includes all regional and ethnic culture into national studies, taking it beyond its earlier, more Han, confines.

Perhaps inspired by the new concept or maybe simply misunderstood, as is so often the case when academics indulge in navel-gazing, guoxue has become more and more open to a myriad of interpretations. In worse case scenarios, and often driven by profit, some merely use it as a name to garnish something completely different.

For non-academics, guoxue’s popularity has boomed through various adult training programs that offer to change people’s lives and better their careers—a sort of lowbrow self-help Confucianism that has proliferated in many aspects of society. Such guoxue is promoted to CEOs and government officials at the highest level, as a must-know for their management and decision-making duties. Judging from its lofty ideals, such studies are certain to prove more useful than, say, a Stanford MBA. “To draw wisdom from national studies and reach a higher spiritual state” was stated as the core objective of one typical Peking University guoxue course, which cost 100,000 RMB per year, covering the more predictable topics such as Confucianism, Buddhism, Daoism and Chinese history, but also the more unusual, such as an array of health tips drawn from Traditional Chinese Medicine. Such guoxue not only promises to benefit the rich and powerful, but also to aid ordinary people in their daily lives.

Li Yaojun, a 48-year-old former high-school teacher of “Moral Cultivation” class, is now busy public speaker booked by private companies and local governments alike, all year round. His topic of the day is Di Zi Gui, which he calls “people’s guoxue.” Boxes upon boxes of Di Zi Gui pamphlets, which he has meticulously revised, abound in his office. “Organizations with goodwill fund the printing,” he says, adding, “when the leader of an organization learns the positive energy Di Zi Gui can bring, they invite me to talk.” Among Li’s audience are company employees, students, community residents, hospital staff, and, somewhat surprisingly, even prison inmates. Li first used the teachings as educational material for his then 12-year-old daughter, but Li began to believe that such a moral education was equally in need amongst adults. Since then, Li has steadily worked his way up the ladder to become one of the leading Di Zi Gui evangelists.

“The teaching contributes to the happiness of the individuals and the harmony of society,” says Li. “There were times when we lost our culture: Han culture died with the Ming dynasty, our faith died with the Cultural Revolution, and our morality died with the economic reform; such loss greatly damaged society and caused all kinds of problems—corruption, pollution, and food safety issues.” If Li is but a well-intentioned, somewhat naive, advocate of people finding morality within a traditional culture, there are cases of people taking it to greater extremes.

Some guoxue institutes have targeted women in an effort to transform them into better wives and mothers with the teaching of traditional “women’s virtue (女德).” Journalist Ye Erniang recently went undercover to join a guoxue camp named “Mengzheng Guoxue Institute” in Guangdong and discovered that not only was its teaching totally off the mark, but the entire camp had unnerving, cult-like characteristics. While the course was free and offered women the secrets to “enjoying a happy family life while having a successful career,” it also encouraged the donation of large sums of money in exchange for solving the female students’ family troubles via further personal guidance. Asking women to dress plainly and to sit in an inferior position to their husbands at all times was one of the least worrying aspects of the course; in what would, no doubt, have had many feminists sharpening their knives, it also encouraged women to never divorce or fight back when they receive verbal or physical abuse at home.

“If women want to focus on their careers so much, why don’t they just cut their uterus out and their breasts off to get rid of all their female characteristics?” lectured one of the camp’s teachers, adding, “Men and women have their own natural duties; follow your duties and you will find the truth of the universe.” The course also claims that diseases can be cured naturally when patients achieve enlightenment. By the time the undercover journalist joined, the camp had already held over 100 sessions, and most of the students were returning ones, many bringing their family and friends with them. The guoxue education market is crowded with many players, big and small, from the extremely unregulated to the downright scary, all seem to appeal to what is a very clear and present need.

Such a need can be further illustrated by the landscape of the current mass media. A TV program named Lecture Room (《百家讲坛》, literally, “The Hundred Schools of Thought Forum”) has often been attributed to stimulating the public’s interest in guoxue. Running for over a decade on CCTV-10, the science and education channel, the program aims to “let experts and scholars serve the people” and build a bridge between academia and the masses. Lecture Room is a hybrid TV lecture and documentary where experts, researchers, and university professors explain their area of expertise to the public. Originally it featured eminent physicists Stephen Hawking and Tsung-Dao Lee, writer Mary Poovey, artist Wu Guanzhong, and even Bill Gates; the program was poorly received until it switched its angle to exclusively featuring Chinese history, literature, and traditional culture. “‘What does this black hole have to do with me’, the ordinary people would think,” says Lecture Room’s former producer Nie Congcong. “It’s just too far away from their life. Public demand is essentially why we changed the show.”

The program took off in 2004 via a series of lectures by historian Yan Chongnian on the emperors of the Qing dynasty. Ever since, it has become a star factory for scholars. Yu Dan (于丹) on The Analects of Confucius, Yi Zhongtian (易中天) presenting Romance of Three Kingdoms, and Liu Xinwu (刘心武) lecturing on The Dream of the Red Chamber—all became overnight scholar sensations, gaining attention approaching an academic version of pop idol stardom.

“It’s also the social environment,” says Nie. “For instance, Yu Dan’s lecture on The Analects of Confucius in 2006 was just the kind of chicken soup for the soul the masses needed. Back then, they felt the benefits brought by the reform but also sensed pressure and insecurity. Society is heading to a new direction, prosperous at a glance, but people are overwhelmed by it and become restless. So, they look back to history and tradition to seek peace.” Almost 10 years have passed since the show peaked in popularity, but it cast a long-lasting shadow over the modern Chinese masses.

At present, Nie believes that things have changed a little, that the people took a look at guoxue and perhaps found it a little wanting. “The journey through guoxue and traditional culture proved to be not quite successful. Right now, [what people want] is all about what’s practical. ‘Having fun while it lasts’ is the attitude. Look at the two most popular TV shows now: game shows and food or health; it’s all practical. As to the future, it’s a subject ordinary people don’t care about.”

Guoxue came into being through an encounter of China and the West, but it has taken on a wide range of meanings and is studied by anyone from serious academics and powerful CEO’s right through to lonely housewives and confused students. To some, it’s just a hip new buzzword that attracts people and then empties their pockets through any number of expensive courses; to others it brings a concrete sense of certainty mired in tradition, enabling them to calm their bewildered minds in a world of fast-paced social transformation; for a patriotic few it’s a hope, a clinging onto, perhaps some semblance of a national identity in an ever-changing globalized world. China might have 5,000 years of history, but it could be that guoxue, with its broad scope and contemporary paradoxes, turns out to be a roadmap to a unique Chinese modernity.