Doctors and nurses stand alone against violence and a corrupt system

Thirty-year-old Fang Hua, an ER doctor in a Beijing hospital, would seriously reconsider applying for medical school if she could do it all over again. In 2009, Fang obtained a Ph.D. in cardiology from Peking University Health Science Center, one of the top medical schools in China, and then began working in one of the most reputable hospitals in Beijing. All in all, it looked like a promising career on the rise, but it didn’t turn out quite as expected. In the first year, her wages hovered at around 4,000 RMB per month. Having worked for four years, she finally got an insignificant pay rise, which looked all the more humble considering her workload and conditions. Once a week, she has to take a shift that works her from five in the afternoon to noon the next day, starting right after her normal work day. This means that, once a week, she works a 28 hour shift, seeing over 100 patients. It’s not the exhaustion that concerns her: “We are used to the workload, and always got by, but I constantly worry that I may misjudge something and make fatal mistakes. The shortage of staff always causes trouble.”

However, there’s an even more threatening force on the ward; for doctors, it can be more deadly than the diseases they face. “On almost every shift, we get a few really cross patients or their families who shout threats at us like ‘I’ll kill you’ or ‘I’ll hack you to death’. Fortunately, none of them have actually carried out their threats on me. I don’t know if they would really do it.” The soft-spoken Fang added, “We didn’t have this many conflicts in the past. I don’t know why. I only hope we will not become the victims.”

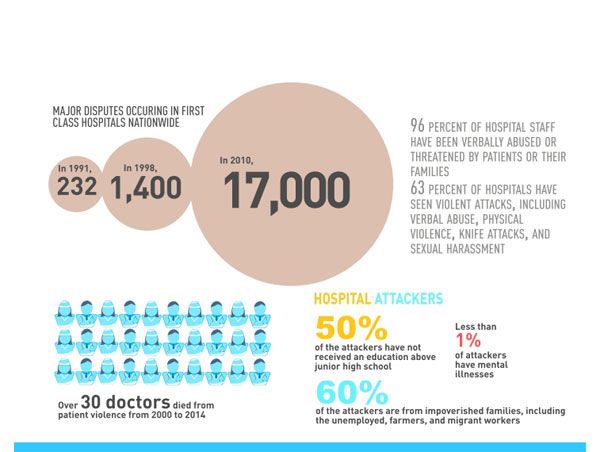

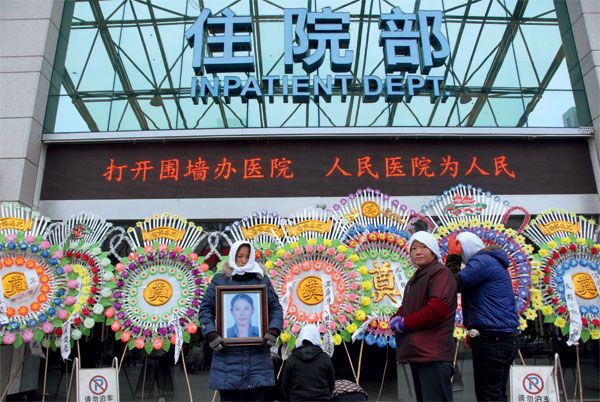

Fang has good reason to fear. Besides the excessive workload and low pay, doctors and medical professionals today face violence from their patients, attacks that have seen a marked increase over the past decade. From 2001 to 2012, over 150 violent incidents against hospital staff have been reported by the media, altercations that vary from physical attacks and kidnapping to public humiliation and murder. According to the Chinese Hospital Management Association, from 2001 to 2012, over 30 doctors died due to patient violence. By 2013, 73 percent of Chinese hospital staff reported being verbally or physically abused by patients. Over 61 percent of hospitals had seen yinao, patients’ demonstrations. In a typical yinao, the patient’s family sets up a mourning hall in the hospital lobby after the patient dies, even bringing in a coffin, floral wreaths, and burning paper money. They accuse the doctors of malpractice or negligence and demand compensation.

This year has already seen more than its fair share of atrocities: 45-year-old doctor Sun Dongtao was beaten to death after an allegedly unsuccessful surgery; 38-year-old Li Aixin had his throat cut by a patient for the same reason; 20-year-old nurse Chen Xingyu was attacked by a patient’s parents, causing temporary paralysis, because they objected to her ward arrangements; a doctor in Chaozhou, Guangdong Province was publicly humiliated in the street after a patient died of alcoholic intoxication.

This horrific series of events has made it even harder for medical professionals to speak out. Public hospitals are theoretically government-owned, and therefore they are not allowed to talk freely to media, just like civil servants. A Communist Party Committee secretary at a medical school, when asked about the rise in violence against medical professionals, told TWOC, “After what has happened in the last few months, accepting interviews from the media is basically out of question.”

Wen Jianmin is one of the few doctors who will speak openly about patient violence. Wen is a large, barrel-chested man in his 50s, with a square, bespectacled face that gives him an authoritative air. He is an osteologist with 30 years of experience, the director of the osteology department of Wangjing Hospital of China Academy of Chinese Medical Science, twice a delegate on the CPPCC, and an activist campaigning for doctors’ rights.

“I know doctors who are picking up taekwondo and nurses who put pepper spray in their front desk—that’s how frightened people are in our profession.” Wen Jianmin spoke loudly and angrily: “Imagine our situation: the first thing that concerns us is not how to cure a patient, but how to make sure we survive the day. When the patients grow violent, we call the police, but they stand by and do nothing until the patients smash our desks or start to hit us. And what does the hospital do? They tell us never to return an insult and never fight back when the patient attacks us. But I never followed this rule.”

He adds defiantly, “I always tell my students to fight back when they are attacked and to make sure their seats face the door so that they can notice if an attacker is coming. When they attack, I am no longer a doctor; I’m a citizen, and a citizen has a right to defend themselves.”

Nurses are in an even worse situation than the doctors. Ma, a pharmacy director in a Tianjin hospital who wished to remain anonymous, said, “In my hospital, humiliation and shouting falls on nurses daily because they do things like miss veins for injections or don’t react to patients’ needs. But, because of the hospital’s rules, the staff can never confront a patient—they can only silently weather them.” The 50-year-old woman added sympathetically, “However, you have to know, every nurse is overworked. In all these years, I’ve never seen a nurse get off work on time at 5 pm. Most of them stay until 11 pm or later. The next morning, they arrive at the hospital at 7 am, as usual. There are no elderly nurses here because you can only stand the work when you are young.”

In response to violence against medical professionals, one medical website made an “Anti-Violence Guide in Hospitals” based on advice given by over 2,000 doctors nationwide. The guide includes suggestions like, “avoid staying in the office on your own or with your back to the door”, “wear sneakers to work”, “save a prewritten SOS message in your phone”, and “shield yourself with your steel clipboard in case of stabbing”.

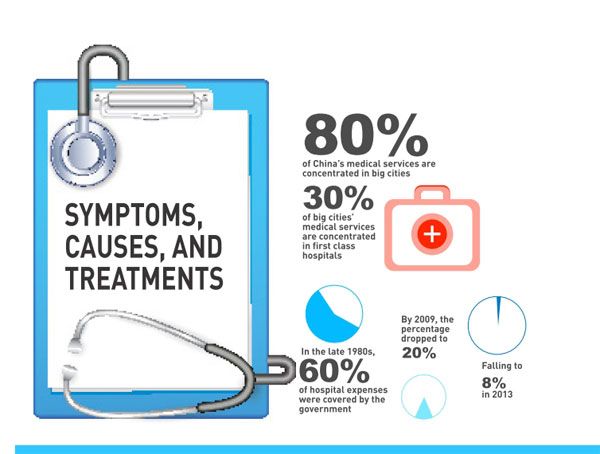

Where, then, does such hostility come from? Admittedly, part of the conflicts arise from the fact that some patients simply lose patience. China’s best medical services are concentrated in big cities. Private hospitals are expensive and sometimes unreliable; public hospitals, especially well-known ones, are permanently overcrowded and understaffed. A trip to the hospital is, sometimes, like going into battle.

In order to look at a leg problem, Kong Weizheng decided to go to Beiyi Sanyuan, a hospital known for its expertise in osteology. He awoke at 4:30 am, taking a taxi to arrive at the registration window at 5:45 am, and, to his dismay, in the misty morning well before the first twilight of dawn, the queue was already 20 meters out of the hospital’s lobby. When he finally got into the lobby, he realized that the line snaked and folded many times over and that the lobby was more crowded than a temple fair. Seven security guards were deployed to keep people in order, and it was far from enough—there were already fights for several spots. Kong got his registration number in what took over an hour and noticed that three departments were already full for the day. When doctors started to see patients at 8 am, the waiting areas in front of their offices were already too crowded to move and Kong had to elbow his way anywhere he wanted to go. “And it’s not a particularly bad day,” Kong said. “Because when I got out of the taxi and was stunned at the sight, the taxi driver smiled and said, ‘Good, it’s not that crowded today.’” All over China, big city hospitals have always been this crowded, and things were even worse a few years ago, with a lack of online and phone registration. But even with these advances, spots in the virtual queue are limited.

While the long waits cause a lot of complaint, distrust is another, more serious, issue. In the past few years, several events have fueled this paranoia for malpractice. In 2010, a man called Chen Cheng sued a hospital in Guangzhou because he believed the doctor sealed his wife’s anus with thread because he didn’t pay the doctor enough hongbao, a sort of bonus or bribe. It later turned out that Chen’s wife had serious hemorrhoid bleeding and that the doctor had tried to stop it. There was absolutely no proof of Chen’s hongbao allegation. But it was too late; the headlines had already struck.

On January 25, 2011, the gate of Jinhua People’s Hospital, Zhejiang Province, was blocked by a family demanding compensation for their loss

“Physician, Heal Thyself” is a story from our “TV Issue”. To read the entire story, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.