Chinese meatballs that bite back

This Huaiyang gastronomic delight hails from the Yangtze Delta in Jiangsu Province and is a bit more fi lling than your usual China fare. Soft and juicy, “lion’s head” (狮子头) is the quintessential Chinese meatball. Its lean pork surrounds green vegetables, and, when done right, the aroma is absolutely mouthwatering. Lion’s head adheres to the core principles of Chinese cuisine: “色香味俱全”, that a truly good dish should “look good, smell good, and taste good”.

The lion’s head is said to originate from Emperor Yang of Sui (隋帝)’s cruise down the legendary Grand Canal. In the city of Yangzhou, officials presented four opulent dishes inspired by four famed local landscapes, following the fashion of the time. But, there was one dish that impressed the emperor, his concubines and officials alike: “sunflower chopped meat” (葵花斩肉), inspired by the beautiful scenery in Sunflower Hills. After the emperor left, the dish gradually became a must have folk dish in the area.

However, the “sunflower” meat dish didn’t “roar” until the next dynasty, Tang (618-907), renamed at the feast of Wei Zhi (韦陟), the Duke of Huan. Upon seeing the dish, this food connoisseur noticed that with the vegetables resembling a lion’s mane, the meat ball is like a lion head. Wei Zhi thus toasted: “To commemorate today’s feast, this dish shall be renamed lion’s head.” In the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911), this southern dish was brought back to the Imperial Palace during one of the Qianlong (乾隆) Emperor’s expeditions south. From a southern staple, lion’s head was adapted into Chinese Imperial cuisine.

However, the “sunflower” meat dish didn’t “roar” until the next dynasty, Tang (618-907), renamed at the feast of Wei Zhi (韦陟), the Duke of Huan. Upon seeing the dish, this food connoisseur noticed that with the vegetables resembling a lion’s mane, the meat ball is like a lion head. Wei Zhi thus toasted: “To commemorate today’s feast, this dish shall be renamed lion’s head.” In the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911), this southern dish was brought back to the Imperial Palace during one of the Qianlong (乾隆) Emperor’s expeditions south. From a southern staple, lion’s head was adapted into Chinese Imperial cuisine.

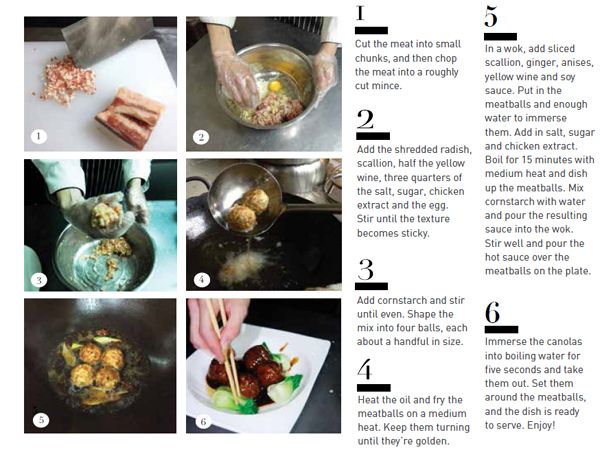

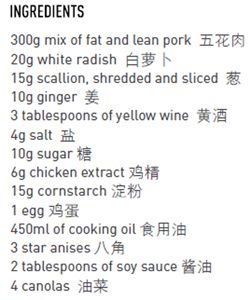

There are many ways to make the lion’s head, but the most popular and the best known is the braised (红烧) style. The secret to making a perfect lion’s head lies in the minced meat, as well as the pot; both determine the dish’s juiciness and texture. Some also add crab meat or water chestnuts for variations in flavor. In the Qing Dynasty cookbook Suiyuan Shidan (《随园 食单》, Recipes from the Garden of Leisure), author and poet Yuan Mei (袁枚) remarked: “Large as a teacup, the texture was tender and exquisite. The soup was especially light, fresh, and delicious; the meatballs melt in your mouth.” (大如茶杯,细腻绝伦,汤尤鲜法,入口如酥。)

A classic dish in Chinese cuisine, lion’s head migrated and was adapted across China. In the North, it’s simply called “giant meatball” (大肉丸子), or the auspicious “meat ball of quadruple happiness” (四喜丸子). The story goes that the former premier Zhou Enlai (周恩来) was a lion’s head fanatic, and it was one of his three favorite dishes. The prodigious artist Zhang Daqian (张大千) was also a master at making lion’s head. Zhang’s tips? Chop the meat to the size of rice grains so that the spaces left in the mixture can lock in the delicious juices.

From the Yangtze delta to the emperor’s table, these lion’s head meatballs have been adapted and changed to suit the tastes of the nation’s delicate palate. Today, it can be found almost anywhere; now it’s your turn to try to add your own spice to this succulent savory dish.