Liuxiaolingtong, who became a legend for his portrayal of Sun Wukong, is more than just an actor—he’s a man on a mission

The underground teahouse where Liuxiaolingtong (六小龄童) chooses for us to meet is the last place you’d expect to find one of China’s biggest TV stars. Tucked away in the basement of an apartment complex in southwest-central Beijing, the teahouse looks like a gambler’s hideout: dim, smoky, and loud. As a bored-looking attendant leads us into a small, fluorescent-lit tea room, I reflect that this is the worst possible place to conduct an interview—it’s dark, it’s cramped, and it’s filled with the noise of shouting men and clicking mahjong tiles. It is, in other words, a place completely free of pretense.

This, at least, is a comfort. When I first started telling Chinese friends that I would be interviewing Liuxiaolingtong—the actor who played Sun Wukong in the popular 80s TV version of Journey to the West (《西游记》)—their reactions made me increasingly uneasy. Eyes widened, jaws dropped, and hands fluttered. This was, I gathered after several conversations, the equivalent of interviewing Big Bird or Mr. Rogers in the US—if, that is, Big Bird or Mr. Rogers were literary characters that embodied 5,000 years of culture, history, and national pride.

Yet when the 53-year-old Liuxiaolingtong sweeps into the room, he looks more like a hip older dad than a stodgy cultural icon; he is wiry and energetic, dressed in a vibrant patterned sweater, rimless glasses, and a red baseball cap. The only hint of celebrity style is the chunky silver rings that stud his fingers and flash in the light as his hands swoop and arc to the rhythm of his words.

“I want to discuss some things with you that I was recently talking about in an interview with National Geographic,” he says as he enters the room, firing off his words like rounds from a pellet gun. Before his scarf is unwound, Liuxiaolingtong is off like a force of nature, speaking with the rapid, emphatic insistence of a man who knows he’s right.

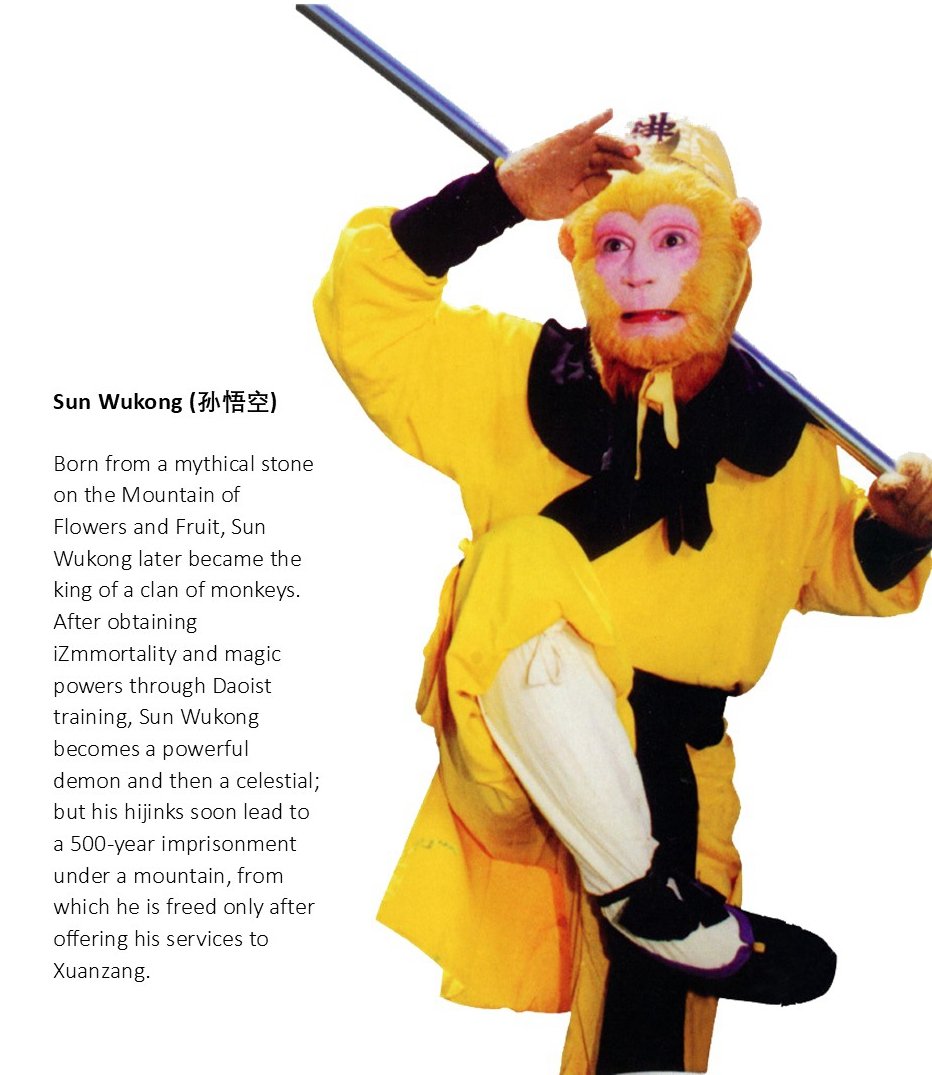

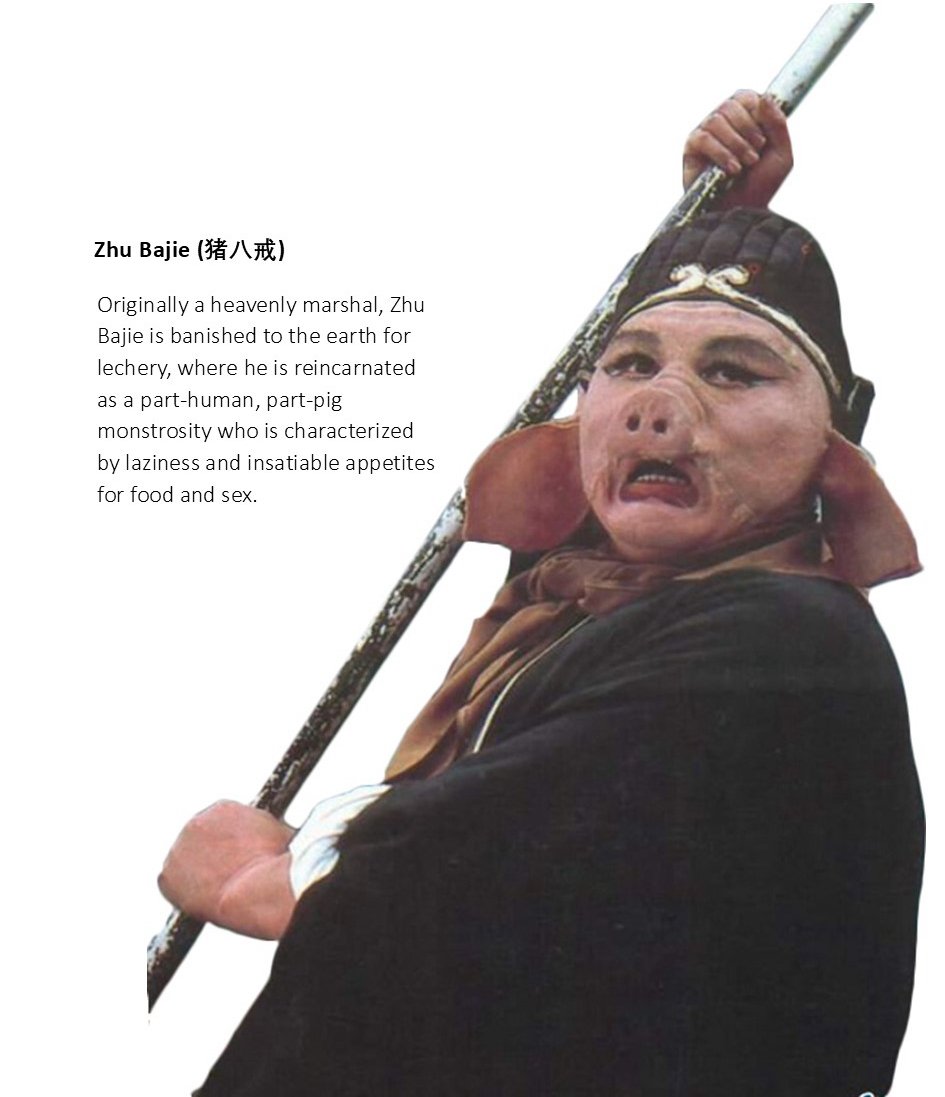

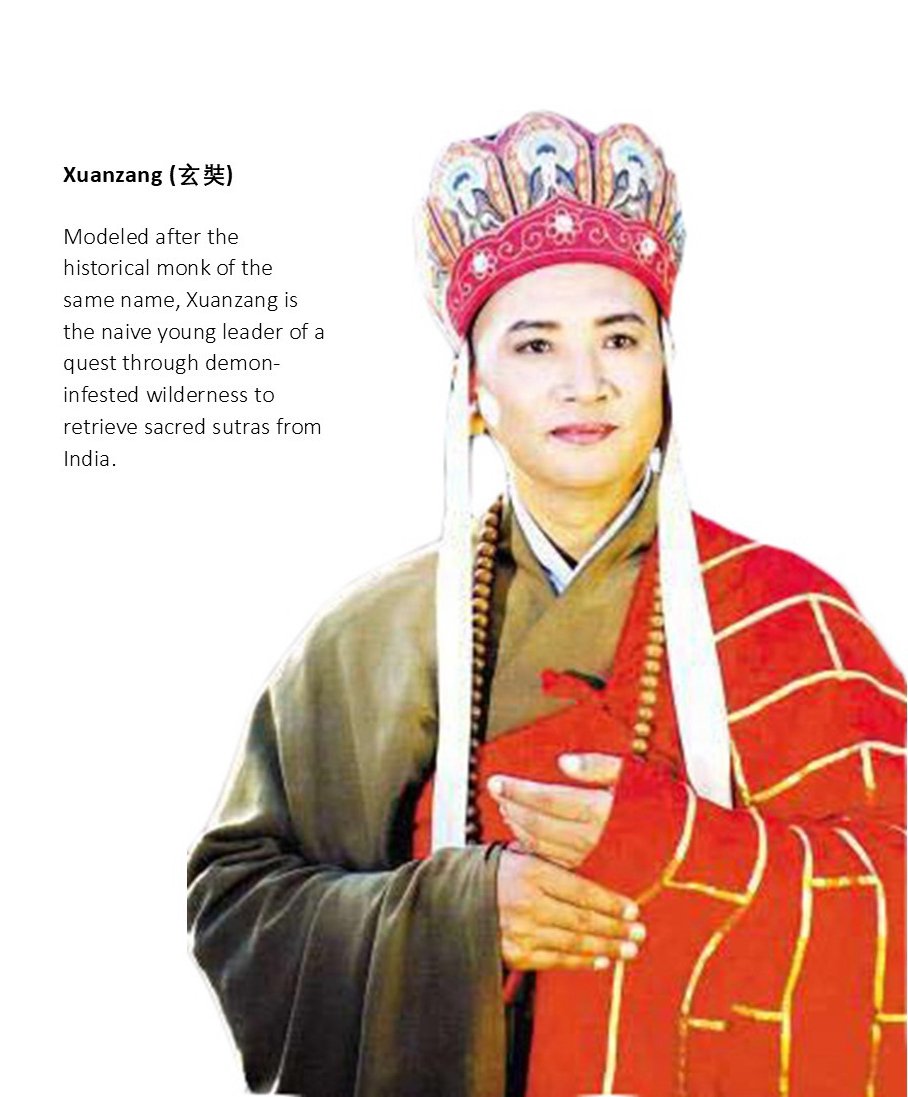

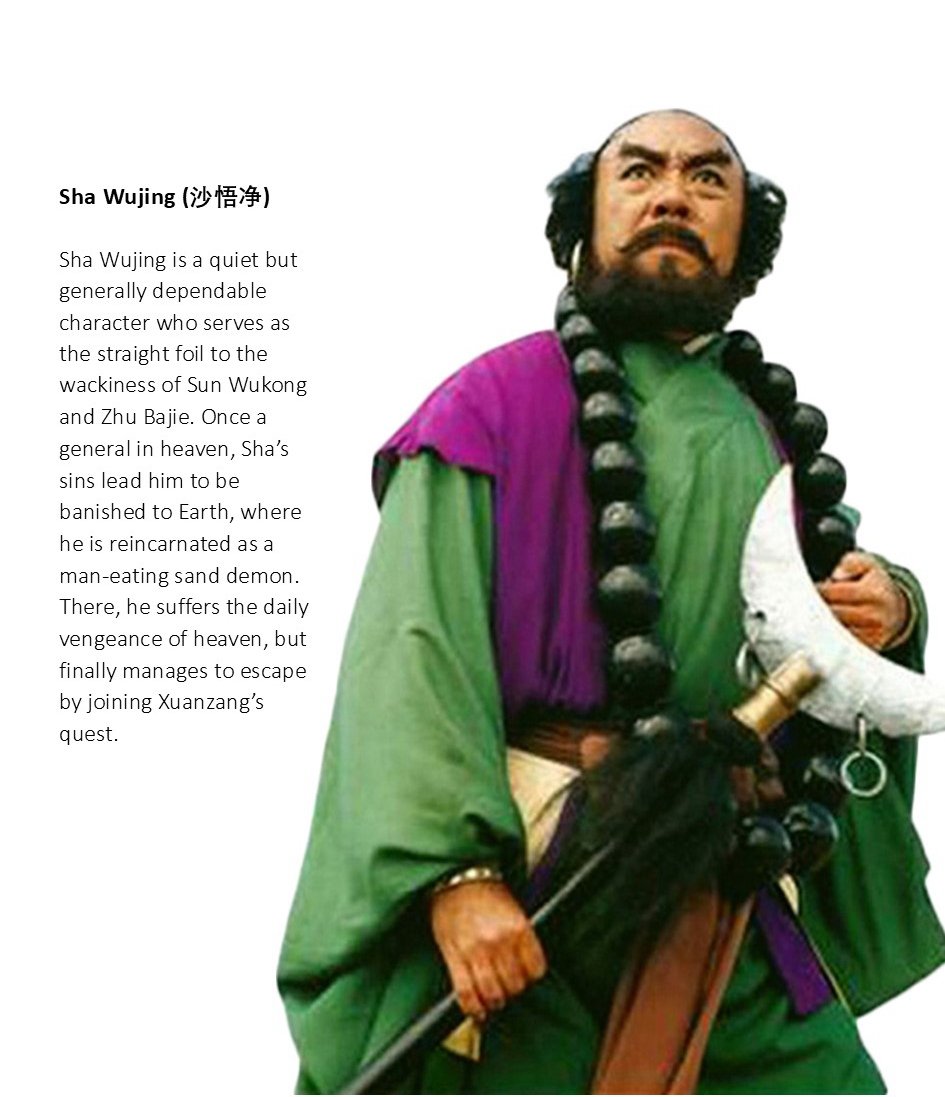

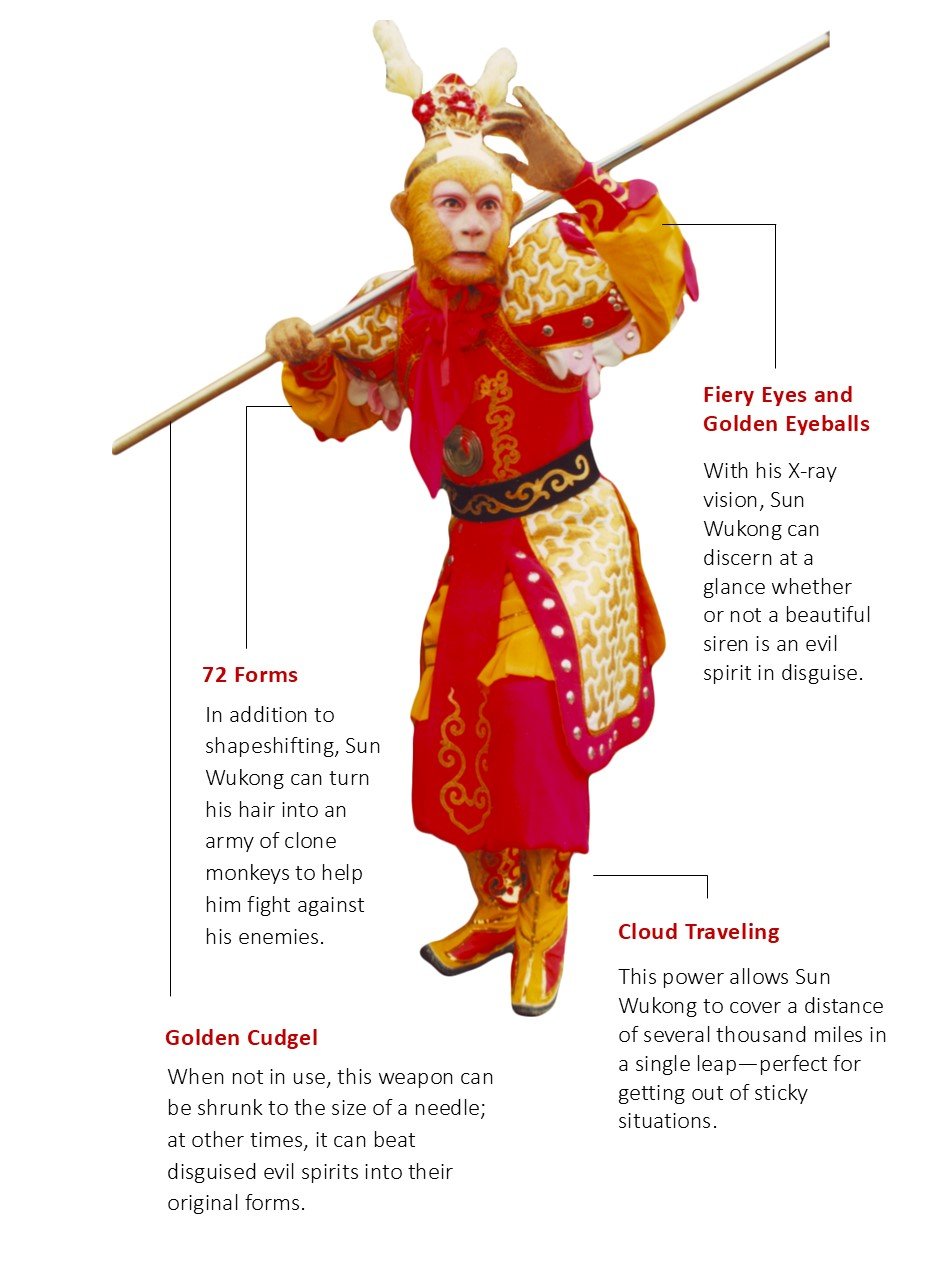

As it turns out, lectures—which is what the first half-hour of the interview turns out to be—are nothing new for Liuxiaolingtong, who these days spends most of his time giving talks at universities across China. The subject matter? His life’s work and obsession: Journey to the West, one of China’s Four Great Classical Novels. Written in the 16th century by Wu Cheng’en (吴承恩), the book is a fictionalized account of Buddhist monk Xuanzang’s journey to India to retrieve sacred Buddhist texts or sutras. In the novel, Xuanzang is accompanied by a team of protectors, all former celestials who’ve been banished from heaven: there is Sha Wujing (沙悟净), a rather colorless monk; Zhu Bajie (猪八戒), a hedonistic creature who is part-human, part-pig; and last but not least, Sun Wukong (孙悟空), the exquisite, impish Monkey King endowed with supernatural powers. Throughout the episodic text, the group encounters a series of malevolent monsters, demons, and animal spirits, all bent on devouring Xuanzang, based on the rumor that eating a holy man would deliver immortality.

Magic, divine grudges, bawdy humor, mythic journeys—this is a heroic saga at its best, a fact to which Liuxiaolingtong has finely attuned both his mind and his tongue, as evidenced by his epic, even grandiose claims.

“The image of Sun Wukong embodies the wisdom of the Chinese people and the ideals of the working class,” he says, settling into his tea. “No matter what their ethnic group or politics, all Chinese people love Sun Wukong because he embodies harmony. Eighty to ninety percent of working people in China know the classic novel Journey to the West through this show, though they may not have read the book.”

Grandiose though he may be, that doesn’t make him wrong. Liuxiaolingtong’s repeated claim that “there is no Chinese who hasn’t watched this show“ is borne out by Hunan TV station’s official statistics. According to their numbers, in 1987, the show garnered a staggering viewer rating of 87.4 percent, meaning that of China’s total viewing audience, 87.4 percent was watching Journey to the West. Their official website also shows that 85.2 percent of all viewers with an education level of junior college or higher watched the show, while 100 percent of illiterate or near-illiterate viewers watched.

Liuxiaolingtong told us that several years ago, he also topped a Sina poll of the most popular television and movie characters, adding that aside from him, the remaining nine characters were all foreign imports.

Still, when you meet the animated actor, it’s easy to see that there’s something beyond ego that fuels his consuming passion for Sun Wukong; something beyond charisma and nostalgia that drives hordes of college students to his lectures. His speech and his body language have a kind of wild, focused energy deeply embedded within him. Or, as the actor likes to put it, “I was born with the soul of a monkey.”

When you read Liuxiaolingtong’s autobiography, it appears as both destiny and a fluke that he ended up as China’s most famous Monkey King. The actor, whose real name is Zhang Jinlai, was born into a family of opera performers who, for four generations, have specialized in playing Sun Wukong. His father, Zhang Zongyi (stage named Liulingtong, 六龄童), was a Shaoxing opera player once praised by Chairman Mao and later became known as China’s “Southern Monkey King.” Despite Liuxiaolingtong’s charmed lineage, it was no sure thing that he’d end up in the Monkey King racket; Liuxiaolingtong was the youngest of 11 children, which meant there were plenty of potential heirs to the Sun Wukong throne.

The obvious choice for Liulingtong was his second oldest son, Zhang Jinxing. “My father thought that Zhang Jingxing was a natural talent at playing the Monkey King, and the most suitable of all of us to become his successor,” Liuxiaolingtong writes in his autobiography, Monkey Fate. “It’s for this reason that he chose for my brother the special name Xiao Liulingtong (小六龄童, Liulingtong Jr.), and started to train him little by little.” Little did he expect that at the tragically young age of 17, Zhang Jinxing would die of leukemia. It wasn’t much later that Liuxiaolingtong’s next brother Zhang Jin’gang—who was also training for the role—would pass away from an intestinal disease. The role seemed to be a curse; or, as Liuxiaolingtong said in an interview, “Everyone in our family was a little scared: could it be that this beautiful Monkey King wasn’t a role that ordinary people could play?”

But even before Zhang Jin’gang’s death, Liuxiaolingtong had already been set on the path by Jinxing, as the actor describes in his autobiography: “My second oldest brother, while he was on his deathbed, said to me, ‘I’m going to die.’ I asked him, ‘What does “die” mean?’ My brother said, ‘Die’ means you won’t see me anymore.’ I asked, ‘Then what do I do if I want to see you?’ He said, ‘If you play Sun Wukong, you’ll be able to see me again.’”

They were words that, on a longer scale, would change Liuxiaolingtong’s life, and, on a shorter one, would prepare him for the day during Liuxiaolingtong’s 12th year that his father called him into the family business. It was during the Cultural Revolution, and both father and son had been recruited to work in a lumber yard. “During one gap in the work, my father looked for a remote place, and, move by move, began teaching me exercises. From the sawmill, he picked up a thin strip of wood to serve as Sun Wukong’s golden cudgel, and, hand to hand, taught me to brandish the cudgel. It was on a rolling tricycle that we set up our own mobile classroom.”

Though Liuxiaolingtong now claims he was an exceedingly timid child (“I was so shy that when the teacher asked the answer to 1 plus 1, I wouldn’t even dare raise my hand!” he tells us, gesticulating wildly), it wasn’t long before he got into the swing of acting. After years spent studying martial arts with his father, Liuxiaolingtong was admitted to the Zhejiang Kunju Opera School of the Arts, specializing in wusheng (武生, a male role in traditional Chinese opera, playing a militant and brave young man). And then, at the age of 23, Liuxiaolingtong was recruited to play the role of Sun Wukong in the TV version of Journey to the West. It was, as Liuxiaolingtong describes in his autobiography, a major role in a major endeavor: “The producers agreed that, in order to make a good version of Journey to the West, the character of Sun Wukong had to be the absolute crux. If, after making the show, the audience thought that Monk Sha or Zhu Bajie were the best characters, then the show would be considered a failure.”

In this respect, Liuxiaolingtong has been an overwhelming success.

“I only ever watch the old version of Journey to the West,” says Zhou Wanfang, a 30-year-old Hubei housewife. “I think it’s because of the monkey. He is capable of many things, but he is not perfect. I like the monkey just as I like Garfield. They are human, unlike Superman or Automan.” It helps, Zhou notes, that in the 80s, television pickings were a lot slimmer, which meant that nearly everyone watched Journey to the West.

“A lot of it was the experience of watching it,” she says. “Nowadays, kids have tons of options, but when I was a kid, my family didn’t have a color TV and I went to my neighbor’s house every day to watch the show. Whatever I watched on a color TV was fun. You would always love something for a lifetime if you loved it as a child.” Knowing the potential that existed, not just in the growing medium of television but in the sheer magnetism of Sun Wukong the character, the show’s director Yang Jie spent months searching for a Monkey King, holding auditions with prominent Beijing actors, all to no avail. It was then that she remembered the “Southern Monkey King,” Liulingtong, with whom she had once worked years before. Liulingtong promptly directed her to his new heir: Liuxiaolingtong, a fresh opera school graduate working as a wusheng player with the Shaoxing Opera at the time. He was hired, but that didn’t mean his training was over.

Liuxiaolingtong is famous for keeping a monkey on set to observe and mimic its movements. He is also known for the punishing tactics he used to give his eyes their characteristic sharpness and sparkle: “When the director of the TV show first found me, she thought my skills were ok, but that there was no brightness in my eyes,” he says. “So to train my eyes, I used to stare at the sunlight and incense until tears would come.”

But the most challenging hump to overcome remained his introverted nature. “I felt the obligation to finish my brother’s career—and to do it, I had to change my personality,” he says. “The director said I was good, but not ‘wild’ enough. Now you can see how much I’ve changed…Art can change your personality; when old friends see me now, they can’t imagine that I’m the same shy boy.”

Among the artifacts that Liuxiaolingtong brings to the interview is a pack of postcards that, in gold lettering, bears the words “Congratulations to Mr. Liuxiaolingtong on the 40th anniversary of his art life.” On the cover is a picture of him as the monkey king in his characteristic stance: cudgel poised, eyes wide and intense, lower lip curled down in a cheeky grimace. But inside are 11 postcards of him featuring roles he’s played between 1982, the year he began Journey to the West, up till 2009. Other notable roles include Premiere Zhou Enlai in the TV series 1939 Enlai Back to the Hometown, author Lu Xun in the opera Poetic China, philosopher and essayist Hu Shi in the TV series Alliance for Peace, and Cheng Zhi, a long-suffering middle school teacher in the film New Year.

Despite this lifelong roster of heroic, even iconic, male roles, Liuxiaolingtong says he has remained firmly entrenched in the public imagination as Sun Wukong. “I’ve played a dozen other roles on TV and movies,” Liuxiaolingtong says, recounting a few of the more famous ones. “But when I got to lectures, people only know me as the Monkey King.”

This, of course, is the maddening side of success; such powerful and well-loved characters as Sun Wukong have the power to make or break a career—and in some cases, do both at once. But while other actors might do their best to distance themselves from such all-consuming roles, Liuxiaolingtong has made it—and the entire culture surrounding Journey to the West—his life’s work. He is, in a word, obsessed.

Most of what Liuxiaolingtong talks about for the first half-hour of our conversation, during which we sit continually poised to ask our first question, revolves around this: the significance of Sun Wukong to the Chinese people and how he has made it his mission to spread what he calls xiyou wenhua (Journey to the West culture) to younger generations in both China and abroad. Mirroring his own experience, he seems to see the novel as both a national birthright and a source of Chinese identity.

“I think of it as my mission,” he says with earnest intensity. “In ancient times, a Buddhist monk went to India to get the sutras, which he then spread to China. Today, I am the inheritor of that monk’s work, spreading The Journey to the West throughout the East.”

Indeed, there is something almost evangelical about Liuxiaolingtong’s conviction that would be absurd if it weren’t so compelling. A large part of what makes it compelling is his personal stake in the matter. Liuxiaolingtong isn’t just an actor who has played Sun Wukong—to millions of Chinese, he is Sun Wukong.

“A thousand people might have a thousand different ideas of Hamlet, but with Sun Wukong people only have one idea—and that’s me,” he says. “My portrayal has been imitated, but no one can surpass me.”

While the actor’s soliloquy is filled with what sounds like bombastic bragging, its arrogance is tempered by his deep respect for the novel itself, and more poignantly by the history that makes Sun Wukong more than just a job—for him, it is an identity, albeit one that has taken a lifetime to grow into.

“When I was young I wanted to do different roles,” he says. “I thought, if Sun Wukong can have 72 different forms, why can’t I? I’ll play 73 different roles.” It wasn’t so much that Liuxiaolingtong couldn’t get other gigs, as it was that the public refused to recognize him in any other capacity.

But eventually, the actor began to internalize the public adulation for Sun Wukong, fusing it with his own sense of familial legacy and historical significance to form an epic feeling of destiny: “Sun Wukong is the Everest of my life; the art, charm, and influence can’t be compared to any other roles I’ve played,” he tells us. “Once, a TV host asked why I thought I couldn’t surpass this role, and I told him it was impossible, so I should shift efforts to promoting monkey culture.”

In this respect, Liuxiaolingtong’s efforts have been vast. In 2004, the actor helped establish a Sun Wukong museum in Huai’an, the hometown of Journey to the West writer Wu Cheng’en, with another one slated to open soon in Shanghai. Liuxiaolingtong also tells us he has plans in the works to open a “Monkey King restaurant” as well as a Journey to the West theme park. He is obsessed with the idea of creating a movie out of one of the novel’s episodes that would incorporate an international cast, and fuse traditional Chinese performance art with modern Western technology. He even set up a “Monkey King” training school for a year in Shanghai, and though it didn’t draw enough interest to be sustainable, the actor says he has plans to revive it as a more general wusheng school. Perhaps most ambitious, he aims at pushing the government toward a policy of preserving and promoting classic works like Journey to the West, “in the same way,” he says, “that they promote economic policies.”

But the biggest part of Liuxiaolingtong’s advocacy has been his lecture series, which over the past seven years has brought him to more than 80 universities. “I fear that the next generation won’t know what the real xiyou wenhua is,” he says again and again. “This is my major mission now, making sure young people know what the real classic novel is talking about.”

For him, “monkey culture” means not only the history and mythology surrounding the novel, but the present-day applications of its lessons, as Liuxiaolingtong sees them.

Like any good evangelist, Liuxiaolingtong has a habit of drawing everything back to his own compelling narrative, and expanding that narrative until it’s reached universal proportions. Like a pastor delivering his sermon, each new thought is punctuated with a verse of sorts: “One should have a plan for his life,” he tells us, pointing to Sun Wukong’s 500 years of punishment spent buried under a mountain. “At first, he was just eating peaches and watching butterflies; then he started to think about his mistakes and make a plan for his life. That was: ‘summarize the past; face the present; plan for the future.’”

His conversation is peppered with such pithy life lessons. The fact that at the end of the novel, the team isn’t able to recover all the sutras means “the journey itself is important: life is full of mistakes, so there’s no point in pursuing perfection obsessively, just enjoying the process.” Then there is the TV show theme song, which includes a call-and-response of, “Can I ask the way?” and, “The way is under your feet.” “It’s another reference to the process of the journey,” Liuxiaolingtong says. “It means that you just have to walk step by step toward your goal.”

For Liuxiaolingtong, that means a single-minded obsession with promoting the legacy of so-called “monkey culture.” Comparing himself with the monk in the novel, in part, allowed him to zero in on a single, life-long pursuit.

“I retraced the path of the original monk’s trip through India,” Liuxiaolingtong says. “I think the monk is an example of doing only one undertaking well your whole life. This monk devoted his whole life to translating and spreading the sutras. I hope to do the same thing with monkey culture and Chinese performing arts. This is my life goal.”

The notion of devoting one’s entire life to a single cause is central not only to Liuxiaolingtong’s understanding of Journey to the West, but to his understanding of his own life.

“My friends have told me that whenever I talk with them, not three words are spoken before I change the topic to ‘Sun Wukong,’ ‘the Beautiful Monkey King’ or ‘monkey culture’,” he said once in an interview. “They ask me, do you really have no self? Do you only live for the Monkey King? Do you only live for the legacy of your family? I say yes—it is impossible for me to have an easy life just for myself. For me, living is a kind of responsibility. And from this responsibility comes an endless chain of delights and stories.”

Images from Journey to the West (1986); Photographs by Olivier Modr