How a bloody-nosed cartoon boy embodies China’s post-80’s generation

“All of you who haven’t handed in your homework stand at the back of the room!” A bosomy, large woman bellowes at the class. A line of kids shivers against the black board. She looms closer to them clutching a bamboo ruler.

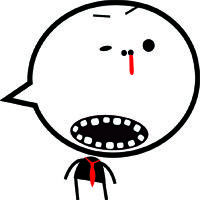

This is a scene from “Kuangkuang’s Diaries (《哐哐日记》Kuāng kuāng Rìjì),” an independent online cartoon whose most popular episodes have been viewed 5 million times. The animation is set in the 1980s and revisits the era through the story of Kuangkuang, a boy in the fourth grade. A drop of blood dangles perpetually from his nostril and he drags a “serve the people” school bag on the ground behind him wherever he goes. He has bad luck in school. The teachers beat him. When bullies accost him he is weak but unwilling to give in.

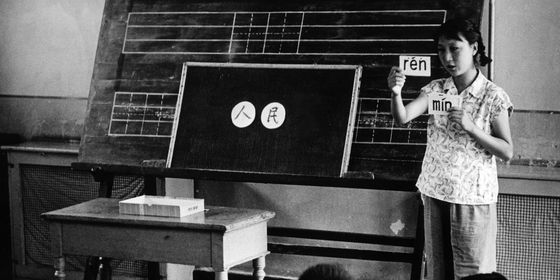

Most of Kuangkuang’s fans are the so-called post-80s generation (八零后 balinghou). The cartoon’s depictions of childhood in the 1980s are so accurate that every episode inspires a new discussion in which viewers excitedly share their childhood memories. “My Chinese teacher was also the teacher I feared most!” “Oh, I had nearly forgotten about the disgusting squatting toilets…” “My classroom also had Confucius and Marx on the wall.” “Seeing these things it makes me want to laugh and want to cry.”

Through Kuangkuang, the post-80s generation nationwide has discovered that, no matter where they grew up, their childhoods were remarkably the same. They all had strict teachers, class meetings, limited varieties of snacks and games, endless homework. Though it doesn’t sound like a very exciting time, these days that generation is obsessed with it more than ever. Kuangkuang fans have even formed an online community called “Kuang People (哐人类 Kuāng Rénlèi).” To cater to this flood of 80s nostalgia, replicas of items from that period have begun to replace the ubiquitous Red Nostalgia Lei Feng and Che products with thermoses, toys, basins and sneakers.

“Kuangkuang is always bullied, but he always holds his head up high,” says Pi San, the script writer and director of “Kuangkuang’s Diaries,” “That’s why he appeals so much to the post-80s. They are not a bunch of lucky people.”

In “Kuangkuang’s Diaries,” no child has siblings. 1980 was the first year of China’s One Child Policy. As a result, most of the urban post-80s are only children. For a long time they were called “little emperors (小皇帝 xiǎo huángdì),” as they became the center of their families’ attention. Their parents, who had gone through the Great Famine and the Cultural Revolution, tried their best to provide their only children with the best food and education they could afford. They were considered the indulged and spoiled generation. But now, the title “emperor” is barely mentioned

.

“When I watch Kuangkuang, I miss the simplicity of my childhood so much,” Hu Xin, a book editor, told me. She married a year ago and is now 28, and her husband are saving for a 20-year mortgage, soaring commodity prices and future childrearing expenses. Her well-paid husband works seven days a week, from nine to ten, in the country’s largest software company. The young couple never had the time to take their honeymoon. “Sometimes I feel like I don’t know myself anymore,” she says. “I just know I’m tired.”

Twenty years ago she was poor, but so was everyone. People had no money, but there was not much to buy. “A family with 10,000 RMB (万元户 wànyuánhù)” was a nickname for the rich, and a five RMB note was a fortune for a kid. With it, Hu says she could by a strawberry-flavored eraser, an iron pencil box, a comic book, a handful of Big-Big bubble gums and a luxurious page of Saint Seiya stickers.

Now Hu Xin is buying a sunny flat and designer bags, but she doesn’t feel the same bliss as when she used to buy bubble gum as a child. A recent survey showed that the average age of mortgagees in Beijing is only 27. This means that the major consumers of the capital’s housing market are young people in their twenties, who will sweat for decades to pay their apartment off. This is the generation that prompted the addition of words like “house slaves (房奴 fángnú)” and “car slaves (车奴 chēnú)” to the 2011 Xinhua Dictionary. There is nothing “imperial” about these once “little emperors.” A popular post online recently made fun of the post-80s situation:

“When we paid to go to primary school, it was free to go to university; when we paid for university, it was free to go to primary schools. Before we had jobs, jobs were state-distributed; when we found jobs, we needed to fight each other not to starve. Before we entered the stock market, even fools were making tons of money; when we entered it, we found we were the fools. Before we got married, people married on bicycles; now that we want to marry, we need a house and a car. Before we started to make money, apartments were free; when we started making money, we found that we couldn’t afford an apartment.”

This sense of deprivation has caused widespread embitterment among the post-80s generation, which makes them love the black humor and occasional South Park-style violence in “Kuangkuang’s Diaries.” In the episode “A One Mao Note (《一毛钱》Yī Máo Qián),” Kuangkuang is robbed of one mao by his teacher’s son. He wants to get it back by seeking justice from teachers, but the teachers are indifferent. He decides to unite all the students who have been robbed and confront the bully, but all the other kids back off at the last second. Finally, he scares the bully by striking his own head with a brick and gets his one mao back. When Pi San wrote the script, he wanted to represent how a child can deal with, or even defy, violence without returning it. “The inspiration was that I myself had been robbed of money in the school toilet,” he says. But as the episode spread on internet and was watched 600,000 times, viewers began associating it with current issues such as migrant workers who cannot get their salaries and China’s recent Red Cross scandal. The episode took on other meanings driven by the viewers’ inner frustrations.

“When the post-80s finally had a right to speak, they found that there were barely any social resources left for them.” Pi San says. “They are unlucky. They shouldered most of the pressure resulting from the drastic economic changes happening in China.”

While the post-80s make up the main demography of tax payers and house buyers, the post-90s generation have also gained social attention with their loud voices, egocentric behaviors and new culture. The post-80s have always want to draw a clear line between themselves and the post-90s. “No post-90s are allowed to watch (九零后拒绝观看 jiǔlínghòu jùjué guānkàn),” announces “The Diary of Kuangkuang” at the beginning of each episode.

Just as the post-80s were disparaged as “the decaying generation” when they were teenagers, the whole society has continued to shoo the post-90s as brain-damaged, harboring vulgar tastes, soullessly materialistic and too sexually open. Many post-80s seem happy to echo the prejudice. However, it is common to see comments under Kuangkuang episodes like, “I’m a post-90s. I like it. Why aren’t we allowed to watch?”

Post-80s’ main objection, in addition to run-of-the-mill prejudice against the heathenish, rising generation, is that the post-90s have had it better than them, and as a result can’t understand what it was like growing up in the 80s. Post-80s were enraged when, on discussion boards about the cartoon, post-90s decried the teacher beatings portrayed in the cartoon as false. “I never experienced these kinds of beatings!” the post-90s said.

However the biggest difference between the two generations, or at least the one that’s talked about the most, is their experience with sex. The post-80s grew up in a decade when sex was still strictly taboo. In “38th Parallel,” Kuangkuang, as always, is called “a little scoundrel” by his head teacher, this time because he was playing with the girl sitting next to him. The education children received then was that boys could only play with boys, and girls could only play with girls. If a kid played with the opposite sex it was considered indecent, and the only way a boy could show a girl that he liked her was to bully her. The ways to get a little sex education were numbered: pulp literature, health magazines like “Family Doctor” and “The Origin of Humans,” and porn videotapes hidden by parents at home. Those who had never seen a porn video were looked down upon.

A Classmate of the opposite gender? No playing!

The post-90s, by contrast, have grown up in a much more open media environment. “My best friend in my class is a weiniang,” a 14-year-old girl once told me, baffling me with the anime-inspired jargon that means hermaphrodite. She went on to recite an encyclopedia of terms for different sexual inclinations, which, to my post-80s ears, sounded as distant and complicated as Swahili.

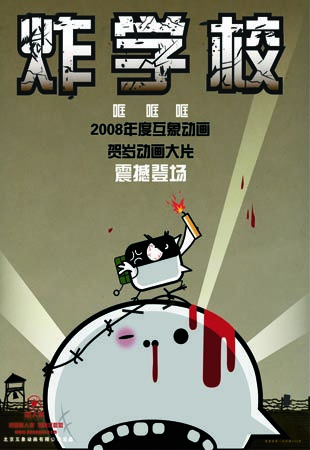

However, the two generations share many things, whether they want to admit it or not. The post-80s were trained under the notion of collectivism. This mindset is ridiculed in an episode of Kuangkuang entitled “Bombing the School” (《炸学校》Zhà xuéxiào), in which Kuangkuang is beaten up (in this episode, to death) by teachers after deviating from the collective. His crime? Giggling and blurting out, “The principal farted!” after the principal breaks wind during a speech. He is alone in his laughter; the other students, of course, pretend to have heard nothing. In Kuangkuang’s time everything was done in unison: in the morning the children read out loud from their textbooks together, then conducted synchronized morning exercises; this was followed two classes later by synchronized eye exercises. In festivals children always did chorus or group dances. They were not encouraged to be individuals. The same activities are practiced in the school system today, which is why, although the post-90s may not completely understand Kuangkuang, still appreciate its sarcasm.

Pi San was able to transcend the gap between generations. He was born in the 1970s himself. “I like the post-80s,” he says. “Compared with us post-70s, the post-80s have more individual values.”

In the episode “My Ideal” (《我的理想》Wǒ de Lǐxiǎng), we are given a look at banhui, the weekly class meeting. “Banhui is the place where children were taught how to lie,” 27-year-old Chen Ruoshui grimaces as Kuangkuang brings banhui memories back to her. In this episode, every kid is required to say what they aspire to be in the future, and they all repeat things like P.L.A. soldier, scientist and teacher (to please the teacher). Only Kuangkuang says, “I don’t have an ideal.” As usual, he gets punished. “He is stubborn. He may be naïve, but he holds on to what he think is right,” Pi San says. “And that’s where the post-80s usually surpass us. For example, Han Han (韩寒) is a representative voice of the post-80s generation. There is no comparable representative of the post-70s generation.”

The young writer Han Han is generally recognized as of the spokesman of the post-80’s crowd, (although the first thing Wikipedia and Baidu mention about him is that he’s “a Chinese professional rally driver”). Han Han wrote the highest-selling novel of the past 20 years, and founded a popular but short-lived literature magazine. His most influential platform, however, continues to be his blog, which deals boldly with controversial topics, especially social issues. “Han Han and his peers do not have our generation’s fear.” Zhang Ming (张鸣), a famous historian born in the 1950s, said to his young audience. “My peers have a lot of fears, although they don’t even know what they are afraid of. I don’t see that fear in young people like Han Han. Your generation should live on like that. You may not be able to replicate Han Han, but you can also be fearless and speak out.”

The young writer Han Han is generally recognized as of the spokesman of the post-80’s crowd, (although the first thing Wikipedia and Baidu mention about him is that he’s “a Chinese professional rally driver”). Han Han wrote the highest-selling novel of the past 20 years, and founded a popular but short-lived literature magazine. His most influential platform, however, continues to be his blog, which deals boldly with controversial topics, especially social issues. “Han Han and his peers do not have our generation’s fear.” Zhang Ming (张鸣), a famous historian born in the 1950s, said to his young audience. “My peers have a lot of fears, although they don’t even know what they are afraid of. I don’t see that fear in young people like Han Han. Your generation should live on like that. You may not be able to replicate Han Han, but you can also be fearless and speak out.”

Pi San shows the same discontent with his own 70s-born generation. “Our generation has been brainwashed by ideological education. We are idealists—but it’s a kind of idealism that makes us always want to represent others, a symptom common of the post-60s and post-70s. The post-80s are way more independent. It doesn’t matter what you do—a shoe cobbler or a programmer, or whatever—it matters that you can think independently. This is what I call a real civic spirit, and I see that in the post-80s generation.”

Pi San always says that “the post-80s don’t have luck,” but the luck they do have is relative. Even though their childhoods were as opressive as Kuangkuang’s and they grew up into an age where a white collar worker needs to work 150 years to afford an apartment in Beijing. Compared with their fathers and mothers, however, they are given more freedom to see their place in the world and think on their own, and some of them, at least, are using that freedom.

– Additional research by Chen Quifan (陈楸帆)

Like the article? You can buy the entire Youth Issue in our store.

Check out our top 5 Kuangkuang vids here.

Kuang Kuang isn’t the only cartoon that’s a hit with Chinese adults.