A new generation of researchers and archivists reexamines the underappreciated history of China-made video game consoles, challenging long-held notions about the devices remembered dearly by millions of Chinese

T he living room is peak late 1990s China—wall calendar, upholstered sofa, tape deck, and Titanic film poster. Pride of place belongs to a boxy analog TV, hooked up to the device that perhaps most defines that era of tech: Little Tyrant, or Xiaobawang (小霸王), a clone of Nintendo’s Famicom video game console cleverly marketed as a study device and famously endorsed by Jackie Chan. To a generation (or two), Little Tyrant was their first introduction to gaming.

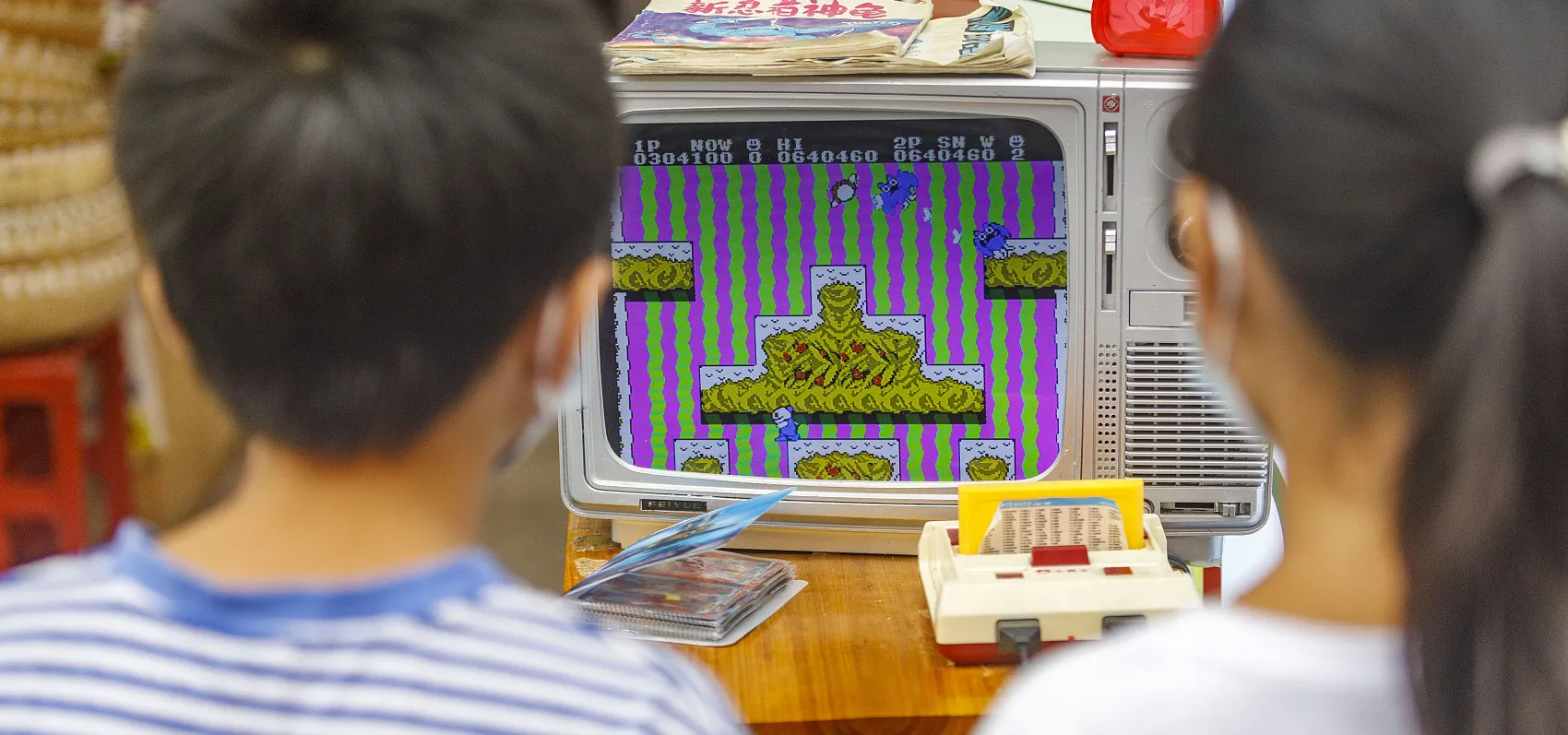

It’s mid-2023, and lead curator Chu Yunfan is guiding a group through a video game archive newly opened in Beijing by the gaming media outlet Game Research Society founded by Chu in 2016. He has been rattling off the standard history, starting in 1972 with the US-made Magnavox Odyssey. Eyes peer down a long main wall housing countless famous foreign gaming systems before the group reaches the living room exhibit. “Here we’ve set up an interactive time capsule; most of you probably don’t need an introduction,” explains Chu, motioning at the Chinese-made Little Tyrant.

Most accounts of Chinese gaming pick up with this console or emphasize its links to piracy and bootlegging. Yet two archives in Beijing (the other one being the Homoludens Archive at Beijing Normal University established in 2018) join similar projects in Shanghai, Guangzhou, and several other cities that seek to revisit this early legacy and reframe the narrative. There is a growing acknowledgment of the diversity of Chinese consoles— and of the technical and entrepreneurial ingenuity, as well as perseverance that birthed them.

Back to the future

There is palpable excitement around the TV as a few people peel off for obligatory rounds of Rambo-esque shooter Contra and tank sim Battle City, while the rest continue to a final display case at the far corner. Inside are peripherals in brown and orange hues—by today’s standards ancient-looking paddles with knobs and switches.

Learn more about gaming culture in China:

- What Video Games (Don’t) Teach Us About China

- Inside China’s Game Boosting Economy

- EDG’s Epic Win Highlights Misogyny in the Gaming World

Here was China’s almost forgotten gaming past. “I think the value of [these consoles] is greater…since most people probably haven’t seen them pop up in books covering gaming history,” says Chu. China’s contributions to gaming history have been historically underappreciated as a peripheral market, even domestically. Little effort was made to document or preserve. The archive is one of the few places to discover early Chinese systems, many turning up zero information online.

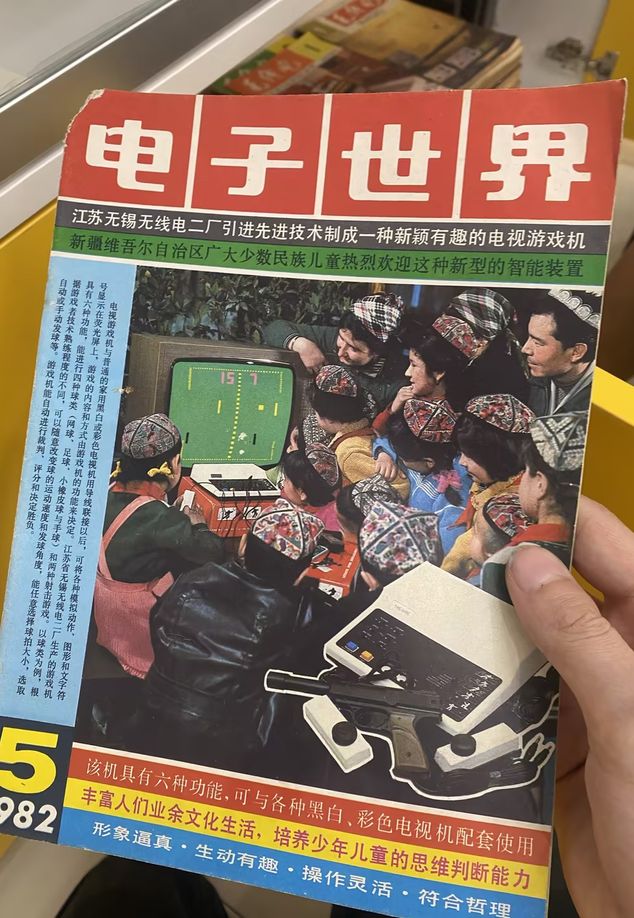

There don’t seem to be any publicly available images of the YQ-1, widely credited as the mainland’s first gaming system. Much like the Little Tyrant to follow, it was a clone, in this case of the famous two-player tennis simulation Pong. It was produced in 1981 by Beijing’s No.1 Institute of Light Industry. The archive boasts a range of such Pong-clone TV gaming machines from Shaanxi, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, all dating from the early to mid-80s.

Also on display is the CY-A from Shanghai’s Chunlei Electronic Instrument Factory, produced around 1980, which may even slightly predate the YQ-1. Consoles of this era, including the CY-A, generally simulated ball sports—mainly owing to limitations of hardware and their “paddle” controllers, where players twist a knob to control a tennis racquet, for example. Switches allow for adjustments to parameters such as ball speed and even new game modes—volleyball, cricket, and soccer featuring similar gameplay with slightly altered graphics.

During these early days of political reform and market opening in the ’80s, with a government keen on catching up in tech, gaming was well-placed in a development push secondary to—but overlapping technologically and strategically with—the important computer industry. It also held built-in appeal to the future of the nation—children. As Deng Xiaoping proclaimed in 1984, “Popularization of computers should begin with small children.” But for gaming to gain a lasting foothold it would need to neutralize the concerns of parents and society at large.

Enter study machines

Things didn’t get off to a promising start. As outside technologies continued to seep into Chinese society, video game arcades became some of the first commercialized entertainment spaces in China, especially in comparatively well-off cities open to foreign trade, starting in the mid-80s. By 1994, the Ministry of Public Security estimated China had 100,000 such arcades, with 60 percent of machines gambling-related. This did little to contribute positively to gaming’s reputation. “Video game culture is simultaneously celebrated and demonized, promoted and controlled in contemporary Chinese society...[there is] this pathological versus productive dichotomy,” writes media studies scholar Lin Zhang in a 2013 research paper published in the International Journal of Communication.

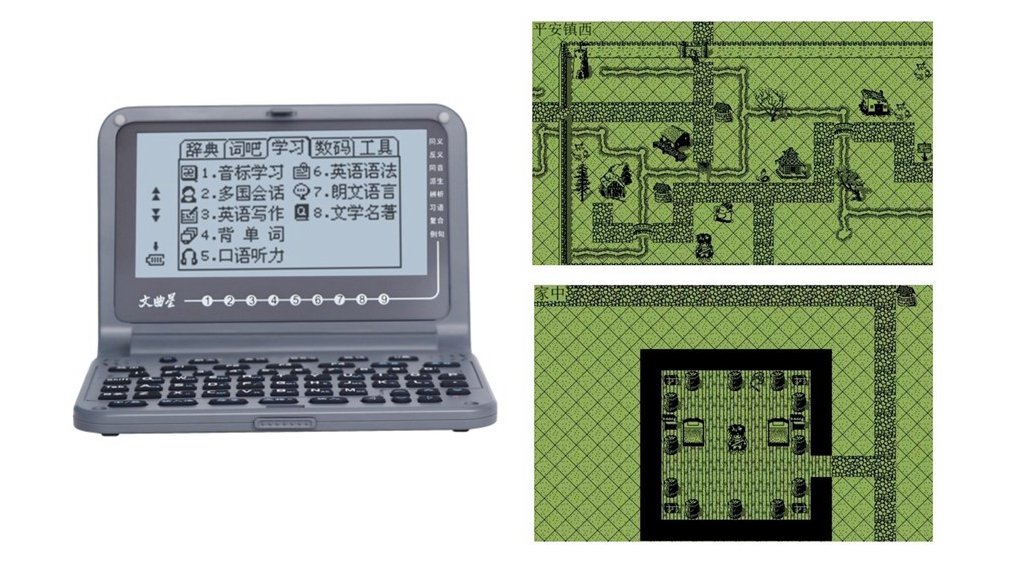

By the new millennium, this ambivalence had culminated in a ban on the sale and import of “electronic game equipment and accessories”—effectively a console ban—that lasted from 2000 until 2014. In such a cultural environment, China’s gaming systems settled on a unique work-around, masquerading as “learning machines” instead. That’s not to say these devices had no study value—take electronic dictionaries, for example.

Between 1995 and 2005, electronic dictionaries evolved into capable multifunction devices; essentially de-facto mini notebook computers. The two leading brands, Bubugao (步步高) and Wenquxing (⽂曲星), each competed off the back of their flagship games Record of Exorcism (伏魔记) and Altar of Heroes (英雄坛说), respectively. As the Gaming Research Society put it in a 2020 retrospective, “Although ostensibly for education, these palm-sized devices also held a hidden gaming function that parents rarely knew.” Far from mere clones, these dictionaries stand as a home-grown innovation responding to specific market and social forces.

The “learning machine” idea goes right back to 1987 with the unveiling of the China Learning Machine (中华学习机, CEC-1) produced by the Computer Science Department of Tsinghua University. CECs were the first range of mass-produced domestic home computers, cloning Apple architecture (modified with Chinese character support). This enabled them to run classic games like Pacman and Karateka. Though swiftly supplanted by IMB-based PCs, China Learning Machines pioneered the gaming device/learning machine hybrid with typing skills training as a core learning function. Typing was an invaluable skill to master due to the inherent challenge of typing Chinese with its sheer number and complexity of characters.

In the ’80s and ’90s, input was based on character shape, with Wang Yongmin’s 1983 Wubi input method being the most popular. Wubi was an explicit selling point for the Little Tyrant (a reported 200,000 yuan was spent to incorporate Wubi input into the console), which launched as a traditional gaming console in 1991, but, feeling the headwinds, rebranded as a learning machine in 1994.

“It came with simple programs like character typing trainers, or with Wubi, which my mom quickly learned. But I never bothered because [me and my dad] quickly found there were lots of game cartridges we could buy separately and play on the machine instead of studying,” remembers TWOC managing editor Liu Jue, whose father bought her a Little Tyrant as a surprise when she was a primary school student in the mid-90s. “From Tank Battalion, and Contra to Super Mario Bros, no doubt all pirated, me and my dad played them all. It also became our favorite family pastime. I remember watching my parents competing in Tetris, and hoping for one of them to fail so I could have my turn.”

Without official support, foreign games like these were reverse-engineered and reprogrammed with Chinese characters—no simple feat given memory constraints at the time. Several strategies were employed: expanding the cart’s memory capacity, limiting the number of characters to the bare minimum, and dynamically loading only the subset of characters required at any given time, among various other compression and efficiency hacks.

Another clever programming trick was figuring out how to store many games on a single cartridge. These cheap so-called multicarts made gaming affordable for the average household at a time when a single imported game could cost over a month’s salary. To create multicarts, programmers had to merge several games and then trick the console into thinking a single game had been inserted. This was achieved by adding menus and hacking the cart’s memory controller or “mapper” to point to the location in the combined code of where the selected game begins. In order to fit, games sometimes had to have their code trimmed or even ported from one kind of chip to another for ease of reproduction, blurring the line between piracy and innovation.

“Early games industries [in China] tapped bootlegging, piracy, and cloning as the infrastructural foundation for legitimate participation in the games industry,” argues sociologist and video game researcher Ian Larson from the University of California, Irvine in the journal ROMchip with reference to research by Sara X. T. Liao, complicating long-held notions about Chinese piracy and bootlegging, a lot of which was borne out of economic necessity.

As curator Chu tells TWOC, “The primary factor driving the market for knock-off consoles in China was price.” The best games were out of reach—and the business-savvy exploited this gap, though successful reverse-engineering and achieving massive cost reductions in manufacturing took exceptional skill, even for the simplest of products. Creating a Famiclone, for example, required cloning two of its chips, including the CPU. It took around five years for Taiwanese firm UMC to crack this.

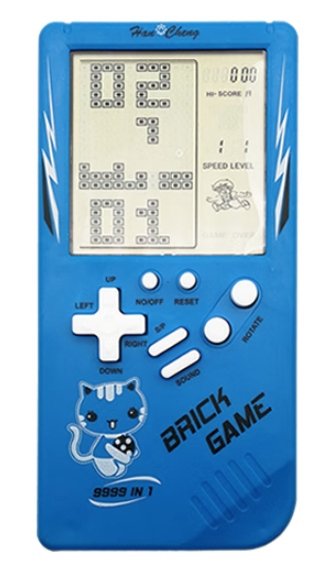

Case in point: In 1990, Tetris was the highest-selling game of all time, but Gameboys were prohibitively expensive (between 500 and 800 yuan, against an average annual salary of 2,200 yuan), yet within a year or so Brick Game appeared, a cheap 2-inch Tetris clone with an LCD screen (costing between 30 and 100 yuan), probably originating in Shenzhen. Its continued ubiquity and availability today are an impressive contribution to handheld gaming—McDonald’s even launched a China-exclusive version in the shape of a chicken nugget in 2023 that garnered wide international coverage.

Handheld heroes

In the decade since the console ban was lifted, there has been a fundamental shift in China’s gaming sphere. Nintendo Switches, PlayStations, and Xboxes are now all readily available and within the purchasing capacity of the average Chinese consumer. But more significantly, China’s own gaming hardware brands have begun to earn name recognition for the first time globally: retro consoles (handhelds and home consoles that focus on the emulation of games from earlier generations) and handheld PCs (powerful handheld computers that allow for portable PC gaming).

Handheld PCs generally run on Windows, whereas retro consoles typically run on Android. This has allowed Chinese hardware manufacturers to make inroads by sidestepping their traditional rivals—running popular operating systems compatible with a huge number of games out of the box. Not that piracy has been totally abandoned. Legally dubious emulation boxes from China, such as the Super Console X, preloaded with tens of thousands of classic games, are openly sold (including in the West on Amazon) and are incredibly popular.

More mainstream products, such as GoRetroid’s Retroid Pocket handhelds, rely on emulation but don’t ship with pirated games (ROMs). GoRetroid, in particular, has carved out a name for itself in the retro scene for its build quality and affordability, and it’s clear that this shake-up in the gaming hardware space has benefited Chinese firms, though Chu cautions that “The current game console market is highly competitive and requires substantial hardware and software content support. Thus, it is unlikely that a domestically developed game console will succeed in the short term.”

In any case, a new generation of historians and curators will continue to catalog and fill their shelves, and in the decades to come, these new Chinese consoles may find their true place—not for a glass case in the corner, but destined for the main wall alongside their peers.

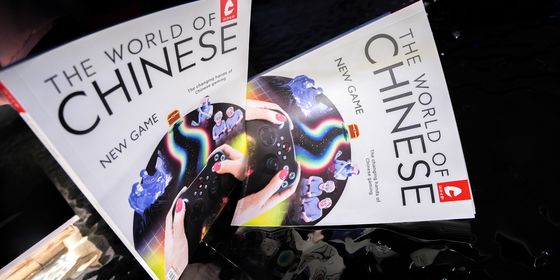

Little Tyrants: A Brief History of Chinese Video Game Consoles is a story from our issue, “Back to the Wild.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.