Lockdowns and provincial border controls frustrate commuters of Yanjiao, a well-known satellite town of Beijing in Hebei province

Two years after she moved out of Beijing and into neighboring Hebei province to save money, Liu Han is now seriously considering paying more than double what she now spends in rent to move back to the capital—at least she’ll be able to go to work more regularly that way.

The 27-year-old originally from Sichuan province, who works in finance and asked to be identified by a pseudonym, claims she has spent less than a month in total working physically at her office in Beijing since the start of this year. Liu’s normally smooth 35-kilometer commute from her apartment in Yanjiao, a town in Hebei province, has been interrupted multiple times this year by pandemic-control measures that locked down neighborhoods, tightened checkpoints on the highway, and sometimes, barred all residents of the town from entering the metropolis across the Chaobai River.

The latest lockdown on Liu’s residential compound ended on May 4, “but it doesn’t matter to those of us who work in Beijing, because we still can’t enter the city,” Liu tells TWOC—referring to what she believes is a common experience among residents in her compound, largely inhabited by commuters like herself.

Less than 20 years ago, there was little other than farmsteads in Yanjiao, administered by the city of Sanhe in Hebei province. Since then, low costs and less restrictive property-ownership laws have attracted an estimated half a million commuters who own or rent homes in Yanjiao while crossing provincial lines to work in Beijing, often daily or weekly.

Until the pandemic, it was a 30-minute drive to Beijing’s CBD in good traffic, or about an hour’s journey by bus to connect up with Beijing’s subway system (though it’s still not for the faint-of-heart, as buses could be standing-room only or require drowsy commuters to queue at 5:30 a.m. to avoid traffic). In the evening, one can make the reverse journey, or catch various ride-sharing or illegal taxi services via WeChat (or touts outside the subway station at Guomao). But for the last two-and-a-half years, even the most determined commuters are finding it’s too high a price for their Beijing dreams.

Liu’s daily commute to work, consisting of catching a bus and transferring to the subway, used to take an hour and 40 minutes each way; but since the pandemic began, it can take up to 3 hours–and that’s when regulations allow her into the capital at all.

The rules are complex, subject to change according to the severity of an outbreak, and vary depending on the direction of the crossing. When crossing from Yanjiao to Beijing in the morning, every person on the bus (which can fit up to 50) has to get out and have their epidemic documents checked: ID, a green “travel code” on their mobile phone, and a negative nucleic-acid test result, either within the past 48 hours or two weeks. A return journey to Yanjiao used to require a negative test result obtained within 48 hours, but now requires the inspection of a commuter pass and a green travel code. Both sides take time, forming huge queues.

Since the start of 2022, the situation has only gotten worse. Yanjiao can now experience a total lockdown, with residents enjoined not to leave the town, if there are just a handful of cases, whereas Beijing’s current strategy is to close down only the compound of an infected person and trace their close contacts. Adding to the sense of unequal treatment are perceptions that Hebei authorities are prioritizing Beijing’s well-being over their own population’s: Sanhe issued a lockdown order on March 15 that made exceptions for logistics workers and companies that supplied the capital city.

Liu estimates that since the start of this year, movement has been restricted in Yanjiao for a total of 56 days, with the longest stretch being 25 days between March 12 and April 5, as Chinese cities step up their efforts to tackle the more infectious omicron variant of the virus. Now, Liu fears for her job due to her prolonged absences—either as a salary cut or being laid off. “It’s overkill,” she tells TWOC.

“Ultimately, Yanjiao is Yanjiao, Beijing is Beijing,” goes an oft-repeated comment underneath articles about pandemic rules in the satellite town. But that wasn’t the prospect sold to the migrants of Yanjiao (as well as similar Hebei bedroom communities like Gu’an county and Xiong’an New District), which saw an uptick in the early 2010s when Beijing’s government announced plans to reduce the city’s population, and integrate satellite towns in Hebei and the municipality of Tianjin into a wider metropolitan area.

Developers advertised Yanjiao as “a secondary downtown” of Beijing after the capital city’s municipal government announced plans to move its offices to Tongzhou district, just 10 kilometers from the center of Yanjiao, which were completed in 2019.

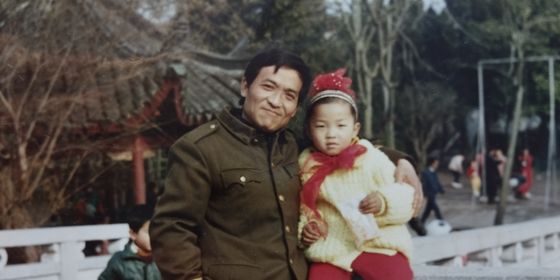

Zhong Ming, a film director and photographer, bought an apartment in Yanjiao in 2012. At the time, he owned a 40-square-meter apartment outside Beijing’s Fifth Ring Road, but he and his wife wanted a bigger property for when they had children. “Several friends of ours had bought apartments [in Yanjiao],” he tells TWOC. “They said it was close to Beijing, the prices were not too expensive, and it would be convenient for children to go to school [in Beijing] in the future.”

Back then, prices for houses in Yanjiao could start as low as 7,000 yuan per square meter, according to Zhong, while the then-average in Beijing was 20,000 yuan per square meter. Moreover, Beijing has restrictions on purchasing property for those without a local residence permit (hukou). Originally from Changsha, Hunan province, Zhong had lived in Beijing and paid income tax for five years, allowing him to purchase one home in the city. But Hebei province had no such restrictions at that time. Zhong still owns his original Beijing apartment, which he now rents out for extra income.

Zhong remembers all sorts of promises from Yanjiao real estate agents–that elementary and middle schools affiliated with prestigious Beijing universities would be opening up satellite campuses in Yanjiao, and that the area was only half an hour’s drive to Tian’anmen square with no traffic (Baidu Maps warns of an hour and a half). There were rumors that Beijing would annex the area, meaning everyone who bought homes there could obtain a Beijing hukou and a return on their property investment. “[In 2015], every day there were fights in the property sales office because people couldn’t buy an apartment,” a Yanjiao native known as “Mr. Ding” reminisced to China Newsweek magazine in March of last year.

The Yanjiao area, including both the old town and the new development area, now has a combined resident population of around 600,000 according to a report by China Newsweek in September last year, representing a 92 percent increase in a decade. Along with homeowners came many seniors who moved to the town for cheaper retirement options, as TWOC found out in 2018, lured by the promise of being within a 40-minute drive to see friends or visit hospitals in Beijing.

But that was before the pandemic put an end to quick movement. To ease the situation, Beijing introduced a special commuter pass in February of this year, which travelers can apply for with paperwork from their Beijing employer and a copy of a housing contract from Yanjiao. This would allow them to enter and leave the capital without having to have a nucleic acid test for 14 days.

But according to Liu, this has had very little effect on traffic jams, as pass-holders still have to queue in the same lanes as other vehicles, and stop to get their passes checked. She has bought an electric bike to bypass the queues of cars. Zhong knows another Yanjiao resident who uses a two-car system: They drive to the checkpoint, walk through the toll booth, then get into a second car they had parked on the other side of the checkpoint from the day before.

Commuter passes are also powerless when lockdown policies override everything else. On the evening of March 12, for example, when the government of Sanhe announced it will require all commuters who work outside of the city to work from home, there was a mass exodus of commuters who wished to keep working in Beijing. Truman Story, a public WeChat account, reported workers rushing into Beijing and sleeping in company dorms, with one worker sleeping in his car for five days. Zhong also fled, as he was scheduled to go on a business trip to Hainan on March 15, and spent two days living near Beijing’s Capital Airport before boarding his flight.

Those without a company to help issue them a commuter pass, such as retirees, have no way of visiting Beijing. One retired senior TWOC spoke to hadn’t been to the city since December 2021.

Some have made sacrifices to keep working during the lockdown. After his return from Hainan, Zhong, who is a freelancer, spent weeks living with friends in Changsha rather than risk returning to Yanjiao and getting locked down. He did not see his son, a primary school student living in Yanjiao with the rest of his family, for 27 days, only recently managing to return home after getting a commuter permit.

Others, like Liu, are working from home, but, “If you work from home all the time, your boss will not like it,” she claims. An article from Vista in March 2021 reported some Yanjiao residents seeing their salaries halved by certain employers, and discrimination in the hiring process against those living in Yanjiao. The uncertainty of when they can return to work also adds to employer’s frustrations.

Zhong predicts that after the pandemic, “there will be a lot of people, mostly renters, who will flee Yanjiao,” willing to pay extra for the greater convenience of living in Beijing. Liu, who currently pays 2,000 yuan per month for a two-bedroom apartment in Yanjiao, and estimates she will have to pay 4,000 yuan extra each month for a place of a similar size and standard in Beijing, is waiting to see whether pandemic policies will change before she makes a decision. “We [commuters] definitely want to live there [in Yanjiao] if it can accommodate us,” Liu says, but “We want to keep our jobs.”

The property market in Yanjiao has also deflated, much to the chagrin of those who bought apartments there to invest in. Numerous outlets like The Economic Observer reported in late 2021 that the People’s Court Litigation Asset Network–which auctions off properties after owners default on their loans–put up 818 properties in Yanjiao up for auction over the course of last year, a fourfold increase on 2019.

Some businesses are also struggling. Li Xiang (pseudonym) the manager of a small Yanjiao hotel, suspended his business earlier this year in order to save on costs, but still has to pay for utilities and rent. Before the pandemic, half the rooms would be occupied at any one time on average, booked by people on business trips or visits to Yanjiao acquaintances. “It’s like being in a house with a leaky roof while it’s raining nonstop outside,” he says, telling TWOC he is barely making ends meet: “I’m staying close to the wall to avoid getting wet.”

In Li’s opinion, the local government should give some form of rent relief to local business owners. If the situation continues, “the service industry will break down and all insiders will lose their jobs.”

What baffles Zhong and angers Liu is that Yanjiao is subject to one-size-fits-all policies along with the rest of Hebei province, and nobody has taken their residents’ special circumstances into account. Both call for more targeted Covid containment policies that are equal to Beijing’s. “[The central government] has repeatedly emphasized that [local governments] should not add additional rules [to what the central government has already issued], but they’re still doing it,” says Liu.

It’s left some bitter, feeling like their livelihoods are being sacrificed for a Covid-free capital. “If you look at this kind of policy or this kind of announcement, you will feel very cold in your heart,” says Zhong, “and feel that you are still inferior to others.”

Full disclosure: Zhong Ming has worked on multiple film and photography projects with TWOC.

Additional reporting by Anita He (贺文文) and Yang Tingting (杨婷婷). Contributions from Hatty Liu and Siyi Chu (褚司怡).

![truecrime-podcast-covewr]](https://cdn.theworldofchinese.com/media/images/truecrime-podcast-covewr.format-jpeg.width-325.jpg)