In the sometimes murky world of China’s game boosters, the promise of easy money masks harsh (virtual) realities

In a small, cluttered apartment in Shanghai, 23-year-old Lin Li is finally getting ready for bed after a long session fighting monsters as a mysterious blue-haired archer on Genshin Impact. Lin spends most of his days completing missions for rewards on the popular Chinese role-playing game—not for his enjoyment, but to make ends meet.

Lin’s one of China’s many game boosters, or dailian (代练), who get paid to play video games on behalf of others who have no time—or will—for the grind. Players hand their precious accounts to these professionals who level up their characters and unlock rewards by killing mythical monsters, collecting resources, hurling spells, or evading assassins.

Lin’s boosting journey began two years ago when he left his tedious job at an air conditioning factory in Guangzhou, Guangdong province. He had worked there since graduating from high school in 2016, and the repetitiveness of the assembly line drove him to seek something new. Now he spends most of his time on his phone, taking orders from gamer clients and playing games. “I’m a freelancer, and not tied to any company. I can leave whenever I want,” says Lin, who requested to use a pseudonym.

Read more about China’s video games:

For Lin and other boosters, the profession promises independence and the chance to turn a hobby into a livelihood. Some work full-time for boosting companies, while others are professionals or students who game boost in their spare time to supplement their income. A few make serious money. When a Chinese game booster known as Pang Mao committed suicide this May, many netizens were shocked by his reported earnings of over 500,000 yuan in two years.

Far from easy money, game boosting is a harsh blend of long hours, stressful conditions, and added social stigma from other gamers and society at large. “You don’t decide your work hours...the clients do. Sometimes you have to pull all-nighters if a job comes in late,” Lin tells TWOC. His longest stretch without sleep was 34 hours, driven by the need to complete tasks for multiple customers.

Game boosting is a massive industry. Tencent’s 2021 Game Security White Paper reported there were an estimated 49.8 million Chinese boosting accounts in the market, worth a total of 14 billion yuan according to 2021 data published by market research company iResearch. On the Chinese e-commerce platform Taobao, a search for “dailian” returns over 30,000 results, with most shops offering boosting services for between 10 to 100 yuan per task or level gained. In an interview with Southern Weekly in 2017, Cai Wensheng, the founder of a popular boosting services platform, said that most of the 4 million accounts on his platform were registered in third-tier cities or below, a reflection of how boosting service providers (companies that often hire dozens of boosters) often operate in small counties for lower labor and rent costs. Research from Professor Hu Fengbin at the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences suggests that most game boosters are in their 20s, with many likely drawn to the opportunity to make money via gaming due to limited employment opportunities and relatively low salaries in these same small cities and rural areas.

However, the market is also highly competitive, and there are significant income disparities. For instance, top-tier boosters can earn 20,000 yuan a month, but the majority scrape by on earnings of much less than that—and live largely according to the whims of their clients. Lin’s monthly earnings rarely exceed 10,000 yuan, and often fall much lower. For comparison, the average monthly income for fresh Chinese university graduates was a little over 6,000 yuan in 2023, according to Chinese consultancy Mycos.

Far from shaking the shackles of his old work, Lin now refers to game boosting as being on the “digital assemble line,” noting that almost anyone can do it. “[In Genshin Impact,] you don’t need any skills or techniques. All you need to do is run, collect materials, unlock parts of the map, and complete simple tasks,” he says. Most of his 100-plus clients are students and office workers who don’t have the time or energy to commit to the game.

Li Ziming, a 26-year-old from the neighboring tech hub Shenzhen, has spent around 2,000 yuan on boosting services over the past year. “I choose boosting because, over time, my passion for games, especially Genshin Impact, has waned. Logging in to complete daily tasks is exhausting, but I don’t want to give up on the game,” Li, who works in the pearl wholesale business, tells TWOC. “Typically, I find two to three boosters for long-term tasks, which costs me about 400 to 600 yuan each quarter.”

One such booster for hire is Huang Xiaochuang, a 22-year-old college student from Guangdong. Huang took up boosting while studying but soon found the pressure to progress weighed on his mental health. “I needed an income source that wouldn’t interfere too much with my classes,” he says. He hoped to monetize his skills in Honor of Kings, a multiplayer online battle arena game he has played for seven years. “I used to love playing games with my friends…Winning or losing didn’t affect my mood. But in this industry, one needs to win more and lose less, which leads to high mental stress.” He sometimes refuses customers when he’s tired, but “To maintain a stable flow of orders, you can’t keep refusing them, so the only option is to delay them,” he says.

Lin’s love for Genshin Impact has similarly waned due to repetition. “This industry is a place where hobbies can easily be worn out,” he says. Nowadays, he rarely logs into his own Genshin Impact account to play for fun.

While going freelance may not be stable but grants boosters more control over their work, opting to join a boosting company can invite shady working practices. According to Lin, these firms take a cut—sometimes as much as 50 percent—of the booster’s fees. “They recruit school kids who are willing to work for peanuts because they think it’s just playing games,” Lin adds. Last July, Legal Daily reported on boosting studios hiring underage teenagers without proper employee registration or ID checks. The children were sometimes made to work from 3 p.m. to 3 a.m. and were provided smartphones so they could circumvent China’s gaming rules, which forbid minors from playing games between 10 p.m. and 8 a.m.

Huang Xiangting, a part-time Genshin Impact booster, tells TWOC that most of the benefits go to boosting companies rather than their employees. Back in 2020, she discovered that her boss at a boosting company was taking a cut of her earnings without permission. When she confronted him, he confessed, and Huang stopped working with him soon after. “But I still envy him. He’s earned a lot of money [as the business owner],” she tells TWOC. “I can’t earn that money [as a booster].”

The industry can also be a struggle for compliant businesses. Zhou Ren established his game boosting company, which now has over 50 employees, in Hubei province in 2021, but claims the golden age of boosting is already over. “The years 2021 and 2022 were great, but now [the industry] is on a downward trend,” the 23-year-old tells TWOC, pointing to increased competition and boosters quitting due to financial pressures and physical stress.

Competition is driving down prices and forcing boosters to work longer hours to maintain their income. “If you charge 25 yuan per hour, someone else will offer to do it for 20, and an hour later, it will be 15…even 10 yuan,” says Lin. He says competitors sometimes steal screenshots of in-game successes from other boosters to falsely advertise their own services.

But a crowded market and dubious employment schemes aren’t the only sources of stress and anxiety. Gameplay adds another layer of pressure, especially in games where success and progress depend on factors outside of boosters’ control, such as the skill level of teammates or opponents. “Sometimes customers just can’t accept failure. They believe that they pay for the service to win. If they lose, they just scold me,” says Huang Xiaochuang.

This pressure can lead to unethical practices, according to Huang Xiangting. “Some boosters resort to using cheats or hacks to ensure they can meet client demands, but this risks getting the client’s account banned,” she says.

Most games prohibit account sharing and the sale of virtual services for real money, leaving boosters in violation of their terms of service. Blizzard, the developer behind popular games such as World of Warcraft and Diablo, recently updated their policies to ban organizations that offer professional game boosting services. Only certain boosting services by individuals that don’t require account sharing are permitted, and they must be paid for with in-game currency. Violators face warnings, suspensions, and even permanent closure of their game accounts.

In practice, it is difficult for games to identify and ban boosters. Real-money transfers take place outside of the game, and account sharing is difficult to track. Regular gamers can, however, report accounts they suspect of boosting behavior. Many report accounts because they view boosters as unfair or cheats, and detrimental to their own gaming experience. “Boosters are annoying as hell,” one 29-year-old Overwatch player from Beijing tells TWOC. “They make the gameplay experience miserable...In China this is called ‘frying fish,’” he explains, referring to when highly skilled boosters play as their clients’ characters in low-level matches and accrue points by virtue of dominating their comparatively weak competitors.

On the popular gaming forum NGA, there are countless complaints about the proliferation of boosters in games like Genshin Impact, Honor of Kings, World of Warcraft, and Overwatch. “Is reporting game boosters of any use?” one disgruntled netizen asked on the NGA forum last August in reference to the in-game rule violation report function. “No, the function is useless. I’ve reported many boosters before, to no avail. How do you prove they’re really a booster?” reads one response.

Beyond the immediate challenges of the games, societal perceptions of gaming as a frivolous activity rather than a legitimate profession add to the burden. Zhang Yi, a 19-year-old who boosts on the popular online battle arena game League of Legends, hasn’t told his parents about his part-time job. “They think gaming is a waste of time,” he says. “I don’t want to disappoint them.” Huang Xiaochuang faces similar disapproval from his family. “They don’t see it as a real job,” he explains. “They’d prefer it if I found something more stable and respectable.”

For some, the societal, economic, and mental pressures are too much. “It’s too exhausting; it’s terrible for your health...I’m looking to do something else,” Lin tells TWOC. “Two years ago I joined a chat group with over 30 other boosters. Now there are only eight left…and not a single one wants to do this long-term.”

Huang Xiaochuang shares this sentiment. While he appreciates the flexibility and extra income, he knows it’s not a sustainable career. “I’ll keep doing this until I graduate,” he says. “But after that, I need something more stable.”

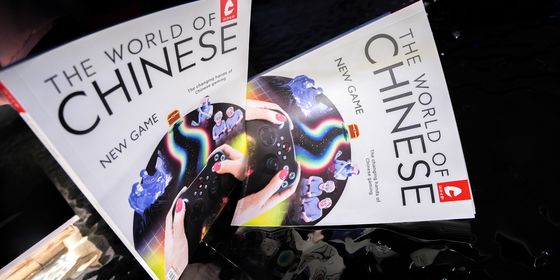

Grinding for Gold: Inside China’s Game Boosting Economy is a story from our issue, “Back to the Wild.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.