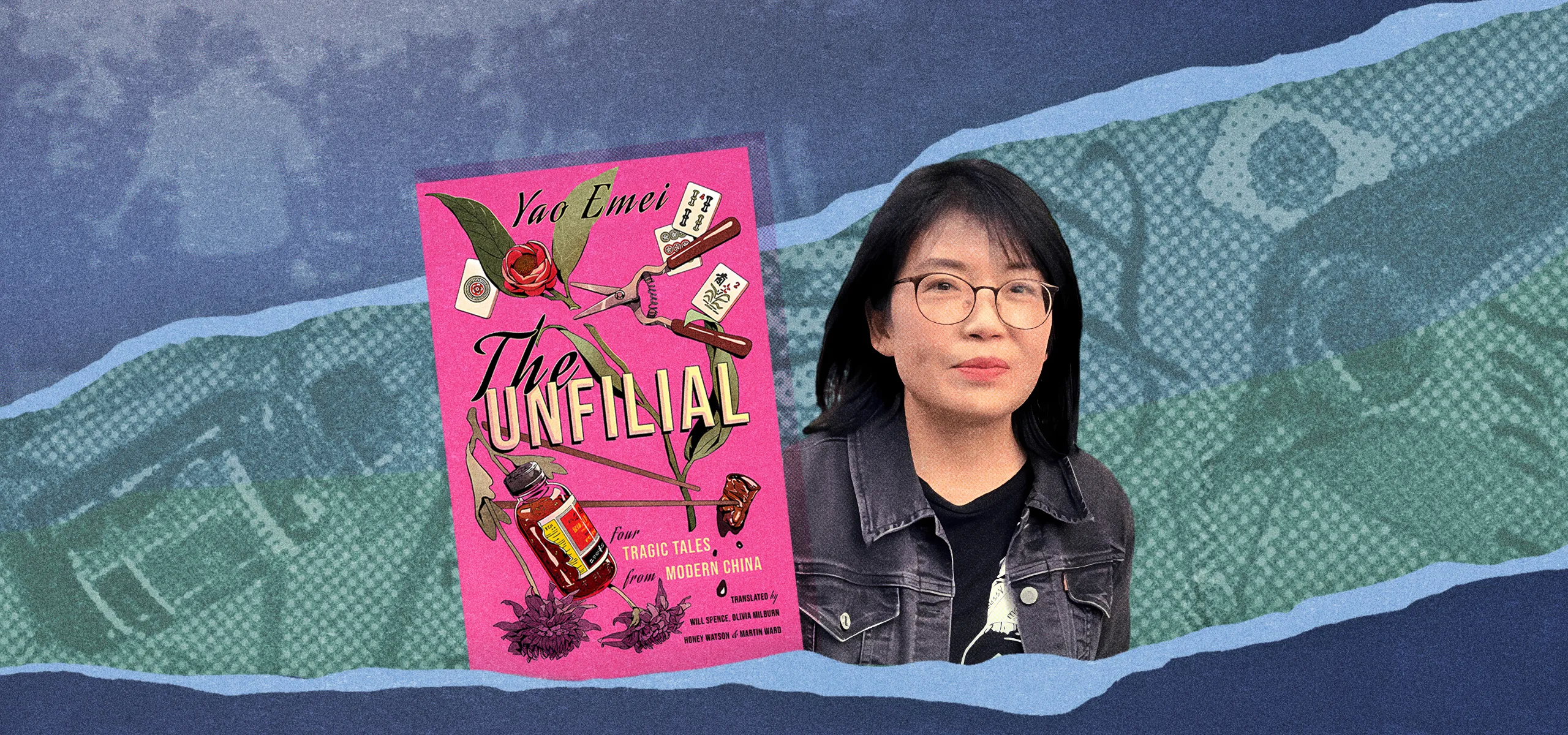

Award-winning writer Yao Emei portrays the dark, brutally honest reality of women’s struggles in Chinese families, often due to men, in her latest short story collection, “The Unfilial”

“The men in our family are cursed,” recounts the unnamed narrator in the short story “It Runs in the Family,” explaining why her sister advised her to change her son’s name to something feminine.

“Ever since I was small, the men of this family have brought me nothing but shame, not a button’s worth of good,” Sister says. There’s Father, who was jailed for racketeering and ruined Sister’s relationship with her police officer boyfriend. Sister’s eventual husband lost his job when the factory went under, and can barely make ends meet. Her brilliant brother Pingzhi died young in a landslide, and her only son Zichen was admitted to a mental institution for killing his girlfriend.

This woeful life story is just one of the four chilling accounts of women in Shanghai-based writer Yao Emei’s latest translated short story collection, The Unfilial: Four Tragic Tales from Modern China. The Chinese version, published in 2021, boasts a glowing score of 8.5 out of 10 from over 8,000 users on China’s biggest book review platform, Douban. Readers praised Yao for painting a grim yet accurate picture of how different women’s destinies are shaped by the troublesome men around them. “The four short stories capture the experience of millions,” writes one reviewer.

Read more about feminist discussions in China:

- The Pushback Against Invasive Sexual Health Exams in China

- Are K-Pop Roadshows a Space for Liberation or Objectification?

- The Struggle Over Female-Only Spaces in China

If you’re looking for encouraging tales of feminist empowerment, this is not the book for you. The women in the stories not only assume the roles of mothers and daughters, but are also wives, girlfriends, older sisters, and in some cases, mistresses. Compared to the English title The Unfilial, the book’s Chinese name, which translates directly to “family life,” seems to capture the essence of the stories more accurately.

In the first story, the first-person narrator, “I,” is romantically involved with her married college professor, who repeatedly impregnates her. In the third and longest story in the collection, “Skeletons in the Closet,” 34-year-old Wei Yuqing starts an affair with the director of a local hospital, who also happens to be her colleague’s husband. Readers can’t help but feel for these characters, despite them being the “other woman” in their relationships. The college professor takes advantage of the innocent “I,” while Wei is victimized by both the director and his wife, the kind and elegant-looking Ms. Cheng. She chooses Wei as one among many “legitimate mistress” for her husband, then conspires to marry off Wei and replace her with another girl after the couple’s son develops feelings for her.

“I reversed the typical moral values assigned to the wife and the mistress, but I said nothing about the man who is loved and protected by both women,” said Yao of the story in a 2022 interview with the Shandong-based media outlet The New Times. “Perhaps, in the realm of marriage and family, men have become so privileged that they no longer feel the need to act.”

Men’s privilege and inaction are recurring themes throughout Yao’s works. In a 2007 article published in the academic journal Literary and Artistic Contention, literary critic Zhu Xiaoru pointed out that Yao’s male characters always appear “diminished.” Zhu attributed the reason for this portrayal to the idea that “once men leave the battlefield or the business world, where they can fully display their heroism, and instead retreat into the daily routines of family life, how could they not feel stifled?”—a belief shared by many of the male characters in The Unfilial.

This belief is most evident in the father character of the last story, “You’ll Do the Job with Skill and Ease.” Despite losing his job, all the family’s money, and their house to gambling debts, he disappears for a whole month instead of taking responsibility for his actions and helping to save for a new home, then expects the whole family to upend their lives once he has returned: The son to be sent off to boarding school; the mother to sleep at the bookstore after working night shifts. While he believes his heroic act will make their life freer and more adventurous, this attempt at modern “homelessness” quickly falls apart, with both the father and mother getting fired from their jobs. “It’s like the Chinese version of Parasite,” reads one comment on Douban, referencing the 2019 Academy Award-winning film.

It’s hard to find any decent male figure in the four stories in The Unfilial. Yet it is not a book praising the greatness of women either. Though the men in their lives cause them never-ending misery, the women in the book never seek to break free from the patterns they have established, adopting instead the attitude of stoic (if not sadistic) self-sacrifice while allowing the men to easily redeem themselves by the slightest show of remorse: Sister in the first story takes care of her father once he has been released from prison, and hires a highly capable lawyer to get her son off his murder charge; Li Nan, the protagonist of the second story, “Gran is on Her Way,” also continues to support her boyfriend following his release from jail, despite his calling her ugly and unworthy of bearing his child. In the last story, the mother considers it immoral to leave her penniless husband.

“A woman’s nature often leads her to see the family as her main battleground,” says Yao in her interview. “She loves her family deeply, worries about everyone, and when someone gets into trouble outside, she is the first to bring them back, tend to their wounds, comfort them, and send them out again only when they’ve fully recovered.” While the stories already read more like cautionary tales than accounts of feminist awakening, comments like these from the author only further distance the book from the feminist standpoint perceived by readers. Born in 1968, Yao worked as a bank clerk and secretary before she started writing in the 1990s. Even after 30 years of writing about marriage and family, she has made it clear that she does not consider herself a feminist and denies that her work has a strong feminist conscience. “I’m never avant-garde nor trendy. In fact, I’m always a step behind the trend,” she said in a 2009 interview with writer Ma Ji.

She acknowledges that she cannot avoid the female perspective because she is a woman, but she disapproves of framing female writers in this way, as male writers are rarely discussed in terms of their gender. “I believe true equality isn’t achieved by simply talking about it or shouting about it. It’s when you accomplish something, and your presence is needed, that equality is realized,” said Yao in the 2022 interview.

Regardless of Yao’s interpretations of her own stories, it’s up to the readers to form their own takeaways from the book. Certainly the top comment on Douban, with almost 500 likes, has made up its mind: “In every broken family, there’s a cowardly, useless man.”