Feminists with disabilities speak about growing up, building a life, and advocacy in the face of physical and social barriers

When 23-year-old Fang Yangyang lost her short life to starvation, abuse, and torture for allegedly being infertile, the perpetrators—her husband and in-laws—were sentenced to just two to three years in prison with probation by their municipal court in Shandong province.

Born with slight intellectual impairments that made it “extra difficult” for her to find a husband in rural Shandong, Fang had married Zhang Bing, a man from a neighboring village 11 years her senior, in an arranged marriage in 2016. Her story echoed that of her mother, an “intellectually troubled” woman whom Fang’s uncle picked up at a train station and brought home as a bride for Fang’s father—likely a victim of trafficking.

Sexual, physical, and emotional violence are a reality for disabled women in China, who often lack economic autonomy, self-defense ability, and awareness of danger. Women and girls with disabilities face greater danger of domestic violence and have lower access to sexual and reproductive health services, with girls living with multiple disabilities being the most vulnerable, according to a national-level analysis of China in 2019 by both the UN’s Population Fund and Handicap International.

China has made some progress in disability inclusion planning and services, but disabled women, amounting to 48 percent of China’s 100 million people with disabilities, remain at the bottom of lawmakers’ priorities. There are currently no national laws dedicated to women with disabilities, or specific protocols to the dangers confronting them, such as being confined, trafficked, and abused.

The neglect from government departments responsible for women and the disabled creates a double burden borne by disabled women due to both their gender and disability. They also create a vacuum of accountability, when the unique needs of women with disabilities are both overlooked by the “women’s matters” agenda and de-prioritized from disability issues.

In society, women with disabilities are also sexualized in the name of security. Whereas disabled men are encouraged to “go out” and break barriers, disabled women are expected to stay at home, as “the outside world is too dangerous for them,” says Ma Wei, former project officer at One Plus One Disability Group (OPO), China’s biggest non-profit organization for disabilities. Marriage and child-rearing are promoted as the highest aspirations for disabled girls, who are often told by their families that they have less to bring to a marriage than an able-bodied woman.

The reproductive expectations sometimes go too far, like in the case of Fang’s mother—by no means an isolated incident of abduction, trafficking, and rape of a disabled woman. Paradoxically, disabled women are also asexualized, experiencing a general lack of sex education in both family and school settings, and are consequently at greater risk of sexual exploitation.

The lived experiences of being female and disabled deserve to be heard, especially from the disabled women themselves. Xiao Jia, Tong Can, and Peng Yujiao, three young women with disabilities working toward disability inclusion in China, spoke to TWOC about their “everyday” experiences and work toward inclusion in the world of gendered disability in China.

Peng Yujiao: I am first of all a feminist

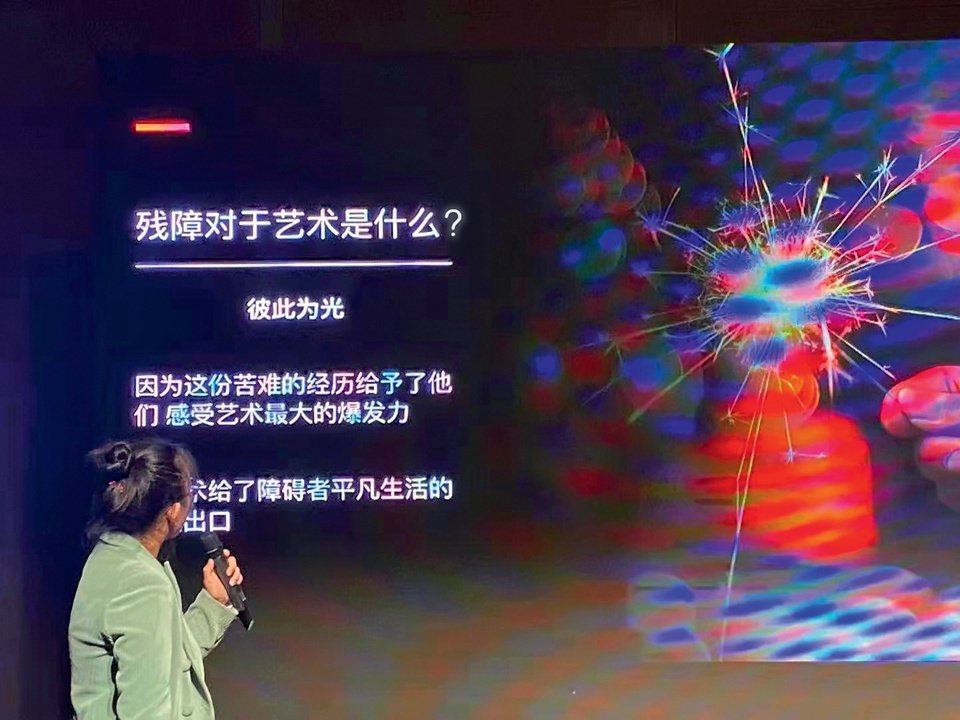

Diagnosed with cerebral palsy at an early age, Peng Yujiao has worked for eight years in the disability sector and co-founded the Beijing Enable Sister Center (BEST), the first feminist disability organization in China. She considers herself “first of all a feminist.”

Peng’s engagement in women’s rights activism dates back to her university years, when she was exposed to a broad range of feminist events. At the same time, she discovered the absence of disability voices in such activist circles. To address the gap, Peng first took part in starting a clandestine feminist book club at university for disabled women. Several members would regularly gather to read feminist literature, and question mainstream ideas of gender and disability.

The seeds of feminism, disability rights, and a rebellious spirit mixed together and budded to form BEST in 2017. Like the book club, BEST was founded by five feminists from various backgrounds, living with disabilities and interested in sociology and social work. Only this time it is not clandestine.

BEST tasks itself with being vocal on behalf of silenced disabled women and girls. They support those suffering from violence and discrimination through prevention workshops, counseling and referral services, and employability training. They aim to build the leadership skills of young disabled women, and conduct research on the living conditions of disabled women in China, including those in rural and underprivileged areas.

“If I manage to awaken these women’s sense of their rights, would they draw further back when they realize they cannot exercise those rights?

However, the organization’s outspoken stance created barriers for their operations. Anyone who has ever heard Peng’s passionate speeches about human rights might be surprised by her pragmatism.

The founders of BEST had tried to register it as an NGO with the China Disabled Persons’ Federation and the All-China Women’s Federation, but each body unhelpfully said a disabled women’s organization should be the business of the other. Instead, BEST is registered as a social work agency and is often hired by the government to provide services. These include organizing public movie screenings for elderly people, community-level disability case management, and planning community events. It was only a facade, but a compromise Peng is willing to make in order to operate.

“The government approaches disability issues primarily from poverty and rehabilitation angles,” explained Peng, arguing there is currently the belief that disabled women need to be protected or cured. There is “a lack of a human rights perspective” recognizing disabled people’s autonomy and equal right to participate in society.

Peng believes that genuine feminism tolerates every cause, voice, and need. At a screening organized by BEST of a documentary on disabled women’s desire and options for motherhood, one able-bodied young woman questioned whether the event was “feminist.” It appeared to her that to speak to women about motherhood only reinforces the idea that women have natural responsibility to give birth.

Peng sees it differently. For her, having children voluntarily is exactly the way to break the stereotypes of disabled women as asexual and nonproductive. Able-bodied women might think it was not “feminist enough,” but what is? “Feminism is about rebellion after all,” she says.

Nonetheless this strong-minded feminist admits occasional frustration. “I sometimes wonder, if I did awaken these women’s sense of their rights, would they draw further back when they realize they cannot exercise those rights, and there’s nothing they can do to change it?” For the moment, she is focused on using her limited power to help those who want to be helped.

Peng is frank about her visions for the organization and for disabled women. “I don’t wish for BEST to grow larger. What I wish is for more organizations like BEST across China,” she says. “Mainly I hope women with disabilities in China could have more agency. We can do more than just wait to be ‘fed’ by charity.”

Tong Can: They blamed my female caregivers

Over the phone, Tong Can’s voice sounds peaceful, yet resonates with power. She works for the Taiyangyu Rare Diseases Counseling Center, a Tianjin-based social work and counseling center that dedicates itself to the mental well-being of people with rare diseases. Tong is in charge of making daily visits to hospital wards, registering and documenting patients’ counseling requests, organizing events for patients, and raising funds for medical aid.

Tong is one of over 100,000 people in China living with osteogenesis imperfecta, more widely known as brittle bone or “china doll” disease. Those who have this rare condition have bones that break easily, as well as short stature, loose joints, hearing loss, breathing problems, and teeth problems. Tong was diagnosed at the age of 21 after experiencing several bone fractures in her teens, but has been able to walk without crutches after a surgery in 2014.

Among the most overwhelming parts of Tong’s condition were the changes in the attitude of people around her. Neighbors in her village near Honghu, Hubei province, pointed fingers at her mother and grandmother, the women who raised Tong—saying it was her mother’s fault she ate frog meat during her pregnancy, and that her grandmother brought Tong up improperly.

In her village, Tong saw that people’s perceptions of disability were different for men and women. Growing up, she rarely saw disabled people. She only realized after she developed her own impairment that some were just invisible. She had never thought of her uncle, who had physically impaired legs, as “disabled”—he just “walked funny.”

Some said it was Tong’s mother’s fault to have eaten frog meat during her pregnancy, and that her grandmother brought Tong up improperly

In contrast, Tong found herself immediately typecast by people around her after developing her condition. Neighbors commented that she would be dependent on her parents for the rest of her life; family members stopped expecting her to be able to work. A relative called her condition a “significant misfortune” for the family.

The social stigma puts significant burden on disabled women in the areas of love, marriage, and sexuality. In Tong’s experience, disabled men didn’t have to worry about finding a partner until after they turned 20, while disabled girls would be squeezed into numerous arranged blind-dates from much earlier ages, told by their family, “Youth is the only thing you have [to bring to a marriage].”

Getting married is the unspoken yet overarching life goal set for these women. Being unmarried, they are considered a family burden, especially to their brother (if they have one). However, if a man is disabled, it’s deemed perfectly normal for their single or married sisters to live with and look after them.

When the disabled women in Tong’s village manage to marry and become mothers, they are sidelined in giving childcare by relatives, who sometimes will even remove the child to their own home; or if that doesn’t happen, they are expected to perform heavy child-rearing tasks at the same level as able-bodied women.

Social prejudices form a sophisticated dating hierarchy for disabled women in rural areas. Disabled women aspire to marry able-bodied men, rather than stay single or have a disabled partner. One result is that rural disabled women often marry much older men who had not been able to find a partner due to their age, lack of wealth, or other factors. After all, noted Tong, marriage is a significant matter of “face” for both parties.

Tong believes firmly in her own autonomy in love matters. She initially protested to the blind dates arranged by her family, but eventually agreed to go on a few. Most of her suitors were relatively well-off men with intellectual disabilities. “Now I think there’s a certain wisdom to it,” she said with a laugh. “I don’t have mental issues. So if I pair up with a man with an intellectual disability, his able body compensates my impairment, while I remain the ‘mind’ of our relationship.”

Tong is also ambivalent about portraying people with disability as victims, and wonders if it is a “necessary evil.” “If pity effectively brings good outcomes to people with disabilities in policy, awareness, and resources, is it so wrong?” she muses. “When people with disabilities benefit from paternalistic protection, does the concept of ‘rights’ remain the single most important thing?”

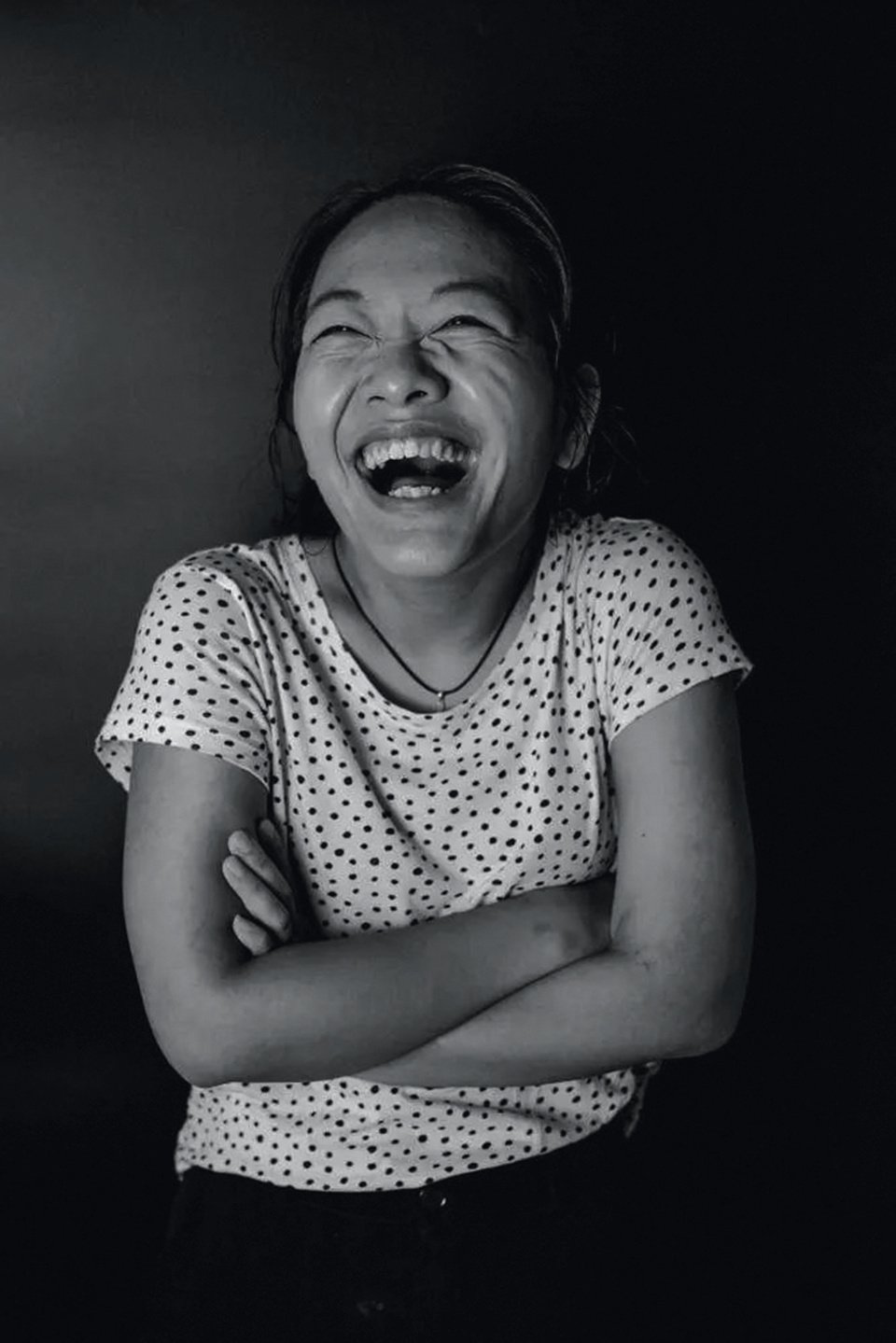

Xiao Jia: You are only seeing the beginning

Xiao Jia is the first non-visual makeup artist in China. Once, during an interview with a journalist, she was asked if it was a shame she has never seen her daughter. The question struck her immediately—is it only possible to “see” with sight?

At 14, Xiao was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa, a visual disease with symptoms of decreased night vision, loss of peripheral vision, and eventually vision loss. She initially coped by disordered eating, as well as planning to end her own life upon turning 20, when doctors predicted she would lose all remnants of her sight. She figured she could at least spend six more years with her dad this way.

When she turned 16, Xiao was placed in a school for the visually impaired. It was her father’s idea for her to become a masseuse and one day own a massage parlor. Massage is the most widespread of the (few) employment options for the visually impaired in China, a trade supported by government-run training programs and special schools.

But Xiao experienced constant sexual harassment in the massage industry: forced physical contact, face and genital touching by the client, and requests to have the lights off during massage. Xiao recalls one client who tried to grab her hair and rip her skirt. Harassment even came from her male co-workers.

Xiao was on the point of taking martial arts classes to protect herself, but then encountered the One Plus One Disability Group. Their podcasts, which featured disabled people telling stories of defying stereotypes and excelling at tasks not expected of them, made her realize there is nothing that disabled people cannot do given proper accommodation. Eventually, Xiao decided to leave her home in Nanchang, the capital of Jiangxi province, to join the organization in Beijing at any expense.

“When able-bodied women are fighting for equal pay, we are fighting to get paid. When they are fighting for equal distribution of domestic work with their husband, many of us cannot do housework, or have a husband.”

At OPO, Xiao came to lead the Disability-Affected Women Support (DAWS) program, which works with women with disabilities and the female caregivers of disabled people. Their most wide-reaching project, “You Are Only Seeing the Beginning,” has gathered 1,600 disabled women in four regions of China for group activities such as cooking, excursions, seminars, or karaoke. These activities foster solidarity and community among the women, while challenging society’s perception of disabled women as “miserable and highly dependent,” said Xiao.

Yet Xiao feels movements surrounding female and disability empowerment are totally disconnected in China. She once led a project that aimed to join together disabled persons’ organizations and women’s organizations to combat gender-based violence. At a workshop, the two parties came to a stand-off: The women’s organizations were afraid the demands of disabled women would pose a “drag” on their momentum.

The outcome did not surprise Xiao. She explains most women’s movements aim to present able-bodied women as having “equal strength” to men. Mainstream discourses on gender equality focus on equal pay, equal distribution of domestic work, equal opportunities in the workplace, sexuality, choice, and the elimination of violence.

But apart from violence, the themes barely touch upon the core challenges faced by most disabled women. “When able-bodied women are fighting for equal pay, we are fighting to get paid,” says Xiao. “When they are fighting for equal distribution of domestic work with their spouse, many of us cannot even do housework, or even have a spouse.”

Xiao notes that international institutions also rarely express any accountability toward disabled women. The UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women in 1979 failed to mention disabled women, and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006) does not comment on or acknowledge gender.

Xiao thinks it is wrong to perform a “simple addition” of disabled women’s platforms to women’s rights movements. “What we need is women’s rights as a minimum protection floor for all women, including women with disabilities; and from there, the recognition of the specific needs of disabled women,” she points out. “If the most marginalized groups are overlooked, it reinforces the discrimination.”

Discrimination and stereotypes are the most powerful when they are not seen as such, especially by those who are the victims. Xiao remembers a young visually-impaired woman who questioned the point of providing education for disabled girls. Xiao is often startled by disabled women who have internalized these stereotypes, who come to believe that being both female and disabled makes them “inferior,” and they can demand nothing from society since they “can’t give.”

“First and foremost we need to ‘wake up’ disabled women themselves. It’s not our fault, and certainly not a bad fortune, to be disabled, or to be female,” she says. “What’s at fault is all the barriers that society has constructed for being both.”

Photos from: Peng Yujiao, Tong Can, and Xiao Jia

What It’s Like to Grow Up Female and Disabled in China is a story from our issue, “Dawn of the Debt.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.