Centuries before the Beijing Winter Olympics, Chinese enjoyed a variety of winter sports on ice

With the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics in full swing, Chinese fans have been enthralled by athletes in events from freestyle skiing to skeleton racing.

But even hundreds of years ago, winter sports were a common fixture in northern parts of the country, particularly during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor of the Qing dynasty in the 18th century. In the Qianlong era, bingxi (冰嬉, “ice games”), a grand festival of parades and competitions on ice, were often held to celebrate the Lunar New Year in the capital, Beijing. It was even praised as a “national custom” in a poem by the emperor himself in 1745.

Originating in the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), bingxi grew in popularity during the Qing (1616 – 1911). The “Ice Games Painting (《冰嬉图》),” a spectacularly detailed 578-centimeter long artwork by Qing court painters Yao Wenhan (姚文瀚) and Zhang Weibang (张为邦), is now held in the Palace Museum in Beijing. It depicts a number of competitions and sports that could be seen on ice centuries ago. Here are some of the most popular—perhaps the Olympic Committee might consider adding them to the next Winter Games?

Follow the dragon trail and shoot (转龙射球)

This combination of ice skating and archery became popular during the Qing dynasty and was part of the bingxi celebrations. The competition saw three archways positioned on the ice, flanked by colorful flags, with a silk ball hung by a rope in the middle of each arch. Teams of at least dozens of players would skate across the ice, led by a flag-bearer, while attempting to entertain the crowd with acrobatic maneuvers such as skating backward and on one leg. Once they pass through an archway, the archer on the team would turn around, and attempt to shoot the silk ball with an arrow.

The performance was a fine spectacle, as hundreds of players joined in together, moving in a line like a dragon’s tail, all while weaving in and out of other teams on the ice. The sport was performed by members of the Manchu Banners, with the winners rewarded by the emperor himself. Royalty and high-ranking officials would attend the games, as well as foreign dignitaries, with records showing attendance by ambassadors from Mongolia, Korea, and other neighboring realms.

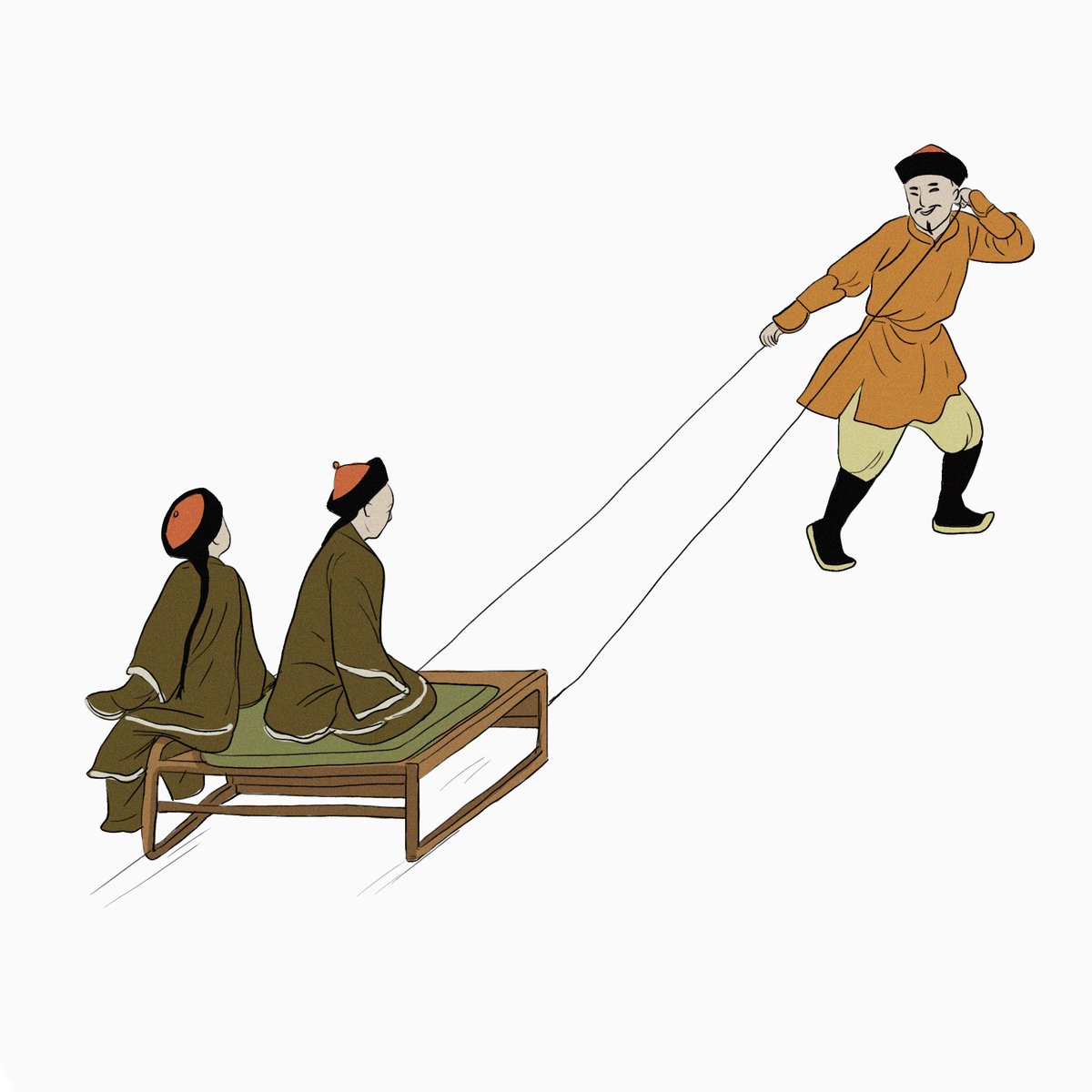

Ice sledge racing (冰床)

Not everyone had exquisite skating prowess or archery skills, but luckily, some ancient ice sports relied more on brute power and speed. Pulling a bingchuang (冰床, literally “ice bed”), a wooden bench on ice runners that can carry up to six people, was one such activity. The beginnings of ice-sledge racing are unclear, but it dates back to at least the Song dynasty, when court official Shen Kuo (沈括) described the sport in his book Dream Pool Essays (《梦溪笔谈》). According to Shen, one man would pull the plank across ice with around three passenger on board, and try to reach the finish line quicker than any of the other competitors.

Originally purely for entertainment, the activity later evolved into a means of transportation in the winter. According to History of the Ming Court (《明宫史》), published sometime in the 17th century, poor people living on Beijing’s outskirts would make money by transporting wealthy passengers on the “ice bed.” The Qianlong Emperor was especially fond of the sledges, and they often featured in his poetry. In “Taking the Ice Sledge Across Taiye Lake on the Day of Sacrifices for Eight Gods,” the emperor writes, “Waiting to cross the river/ I do not know how cold the frost flowers are./ Sitting in my warm sleigh/ I arrived at Yujin Park.”

Ice football (冰上蹴球)

In this game, dozens of players were split into two teams that competed to catch and keep hold of a leather ball thrown into the air above ice by a referee. Unlike ancient Chinese cuju (蹴鞠) football and modern-day soccer, players were allowed to pass the ball with both their hands and feet. A retired Qing official, Pan Rongbi (潘荣陛), explained the rules in his book Festival Customs of the Imperial Capital (《帝京岁时纪胜》), a text chronicling the customs and scenes of Beijing in December and January. In one version of the sport, teams would try to catch the ball before it hit the ice, with the winning team the one who secured the ball. In another version, the referee would judge the winning team based on their teamwork, bravery, and skills.

The Qing government later incorporated the sport into military training, as it could improve players’ endurance, strength, and camaraderie, according to Pan’s book.

Skating like a mountain (摆山子)

Somewhat similar to modern synchronized skating, or the calisthenics performed by Chinese schoolchildren between classes, this sport involved groups of hundreds of players performing coordinated skating moves on the ice together. The heavily choreographed routines could include skaters raising their hands to replicate the style of a swallow in flight, or performing spins and skating backward. During the bingxi parades, each team would be judged on its performance, with the most precise, unified, and entertaining team winning the competition.

Downhill ice skating (打滑挞)

Like modern alpine skiing events, but on more slippery terrain, this sport, also known as “ice slide (冰滑梯),” was popular in the 18th century. On freezing winter days, organizers would water a slope approximately ten meters in length to create a treacherous ice trail for competitors. Wearing primitive leather ice skates, competitors would take turns to slide down the slope with as much flair as possible. Those who made it down the slope without falling would be named the winner, according to Records of a Mediocre Official (《朗潜纪闻》), a collection of anecdotes and history from the Qing dynasty by Chen Kangqi (陈康祺). Like modern downhill skiing, downhill skating could be dangerous and risk of injury was high.

Illustrations by Xi Dahe (喜大河)