What does the success of “Black Myth: Wukong” say about the Chinese gaming industry?

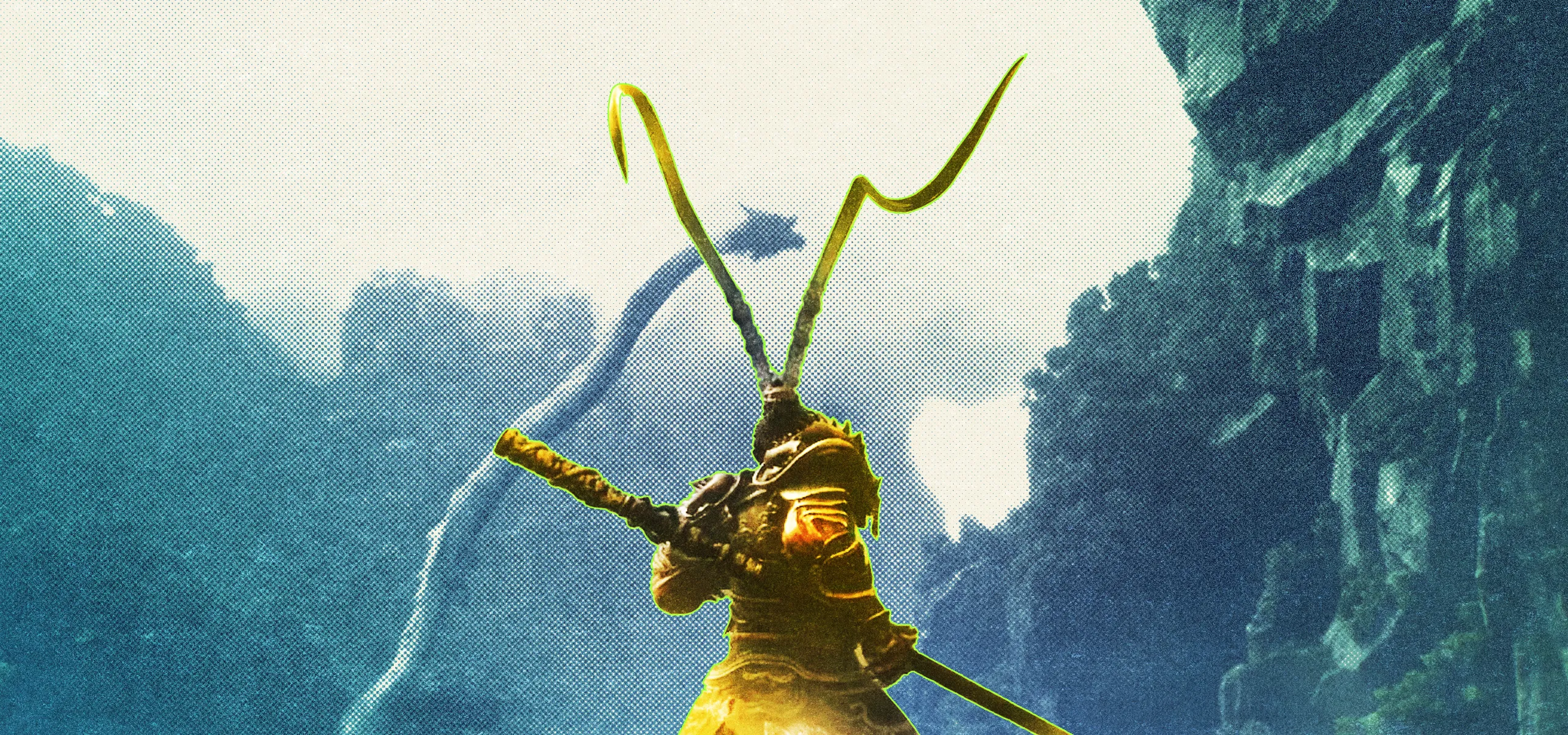

China’s first big-production console game, Black Myth: Wukong, was an instant hit upon its release on August 20. Only two weeks after its launch, it gained over 850 million USD in gross revenue on Steam alone. Based on the 16th-century classic Chinese novel Journey to the West, Black Myth has become a source of pride for Chinese gamers, earning both critical and popular acclaim worldwide. However, some have accused the developers of misogyny, which has dampened the game’s success.

In this episode, we speak with three experts and industry insiders—gamers themselves—about the “Black Myth” phenomenon, discussing the game’s development, industry background, the controversy, and its implications for the future of both the Chinese and international gaming industries.

Guests:

Daniel Ahmad is the director of research and insights at Niko Partners, focusing on the video game market in Asia and the Middle East.

Lundy Lan is a video game technical artist with mobile and console game development experience in China.

Jesse Young is an independent researcher and contributor to The World of Chinese.

Subscribe to the Middle Earth Podcast: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google Podcasts | Amazon Music | Overcast | RSS Feed

The following are excerpts from the transcript of the episode (edited for clarity):

05:00

Aladin: For someone who has not played the game, can you quickly describe what is Black Myth: Wukong? And why is it so important that it came out at this time?

Lundy: Wukong is an action game based on a traditional Chinese story called Xi You Ji (Journey to the West). It’s such a proud moment because there are a lot of people in China who are passionate about sharing traditional Chinese stories and culture with the world. As a kid, I played a lot of overseas AAA games, but their stories were not told from my perspective. So, when the first trailer of Wukong came out, we were amazed that we were finally getting that game.

07:13

Aladin: There was a lot of international press regarding the game. It’s such a watershed moment for the Chinese video game industry, but at the same time, there are also some issues regarding the creators’ team.

Jesse: In terms of it being a watershed moment, the thing is the AAA label. Genshin Impact and a lot of Chinese games are seen as mobile-first, free-to-play games, which means that they have no upfront costs. They’ve been criticized for being a revenue-raising thing with a lot of predatory extra transactions or gambling-type elements. So, it doesn’t have a lot of prestige. Whereas a AAA game, the easiest way to think about it is a blockbuster production. It got the kind of prestige of a Hollywood film or a major novel. This game, being a big AAA game, gets more notice and respect in the traditional outlets. So that’s why it’s a watershed moment.

In terms of the controversies, to give a very short overview: it started with some of the comments made by the art director Yang Qi and the producer Feng Ji about a decade ago. Yang wrote a blog post in 2013 that said, “Men and women’s preferences for games are determined by their physiological conditions.” He does not need to make games for female players, and some things are just for men. They are depressed, they are angry, and they are bitter. So that was seen as a sort of repudiation: Why make games that are particularly for women?

And then, when the trailer for Wukong was released, Feng Ji, the producer of the game, made some remarks that were somewhat sexualized. When he was criticized for this at the time, he doubled down. Many people say it became a Western thing because IGN had a big article last year, but a lot of criticism came from within China and in Asian-focused news outlets back in 2020.

09:48

Aladin: Did this scandal have any effect on game sales?

Daniel: There are always going to be scandals that do affect game sales, but in this case, I don’t think the majority of buyers, or even people who are following it, were aware of any of this. They had no idea what was going on. As mentioned earlier by Jesse, this was something in China that took place four years ago. The comments are a decade old. The controversy happened four or five years ago. Ultimately, not a lot of people knew about it.

10:40

Aladin: Was the success of the game a surprise or not?

Daniel: I think it’s worth giving some background on the market. When we look at China, it’s a 50 billion dollar market this year for gaming alone, making it one of the largest video game markets in the world. The US and China are ahead, and Japan is the third. What’s important is that within the Chinese gaming market, almost 90 percent of their revenue is from in-app purchases and free-to-play games. Premium, as a whole, has always been fairly niche. What’s changed over the past 10 years to make this possible, and what Game Science saw and capitalized on, is the fact that at one point, consoles were banned in the country, and in 2014 that was overturned. We now have a growing console market.

Secondly, there was a lot of piracy for premium games in China in the early 2000s. Now, thanks to Steam and online games, not as much. Digital distribution has certainly helped that out. You also have increased salaries and increased disposable income being spent on entertainment. Chinese gamers are more willing to pay for high-quality content, and that includes games as well.

Though still small, premium games are making up a growing portion of the market. The fact that Black Myth: Wukong can sell for over 800 million in two weeks, with 75 percent of the sales coming from China, is extremely impressive. Because we haven’t seen anything like this since PUBG in 2017, a premium online multiplayer battle royale game, whereas this is a premium single-player game with 30 to 40 hours of content, as opposed to unlimited runs.

13:57

Aladin: Would the game still be successful if there’s no Sun Wukong as the backstory and the whole cultural packaging?

Daniel: This game did have that perfect package. It’s the combination of high-quality action, RPG mechanics, and the Journey to the West storyline. One of the big things that blew up the game was the initial trailer back in 2020, with 55 million views on Bilibili. It showed that they can find the right balance among graphics, gameplay, story, and other aspects. It has become a cultural phenomenon in China overall, leading to not just sales of the game, but that cultural spillover into other aspects, like gaming hardware sales, increased tourism, and increased brand awareness for their partner companies.

15:38

Aladin: We all know that China has been called the factory of the world, but I didn’t know that many overseas AAA games have also been made in China.

Lundy: Many game companies built their teams for art production and outsourcing of foreign games. They typically hire university graduates and train them how to do game development. This lasted for decades. Then many of these companies wanted to make their own games, such as miHoYo. It’s said that at the peak of miHoYo’s Genshin Impact production, they had over 2,000 people working on it, most of them staff from outsourcing companies. In Black Myth: Wukong, the amount of art assets is huge, with many different objects and scenes, but it only took them four to five years to finish.

Daniel: One thing we’ve seen over the past two decades is that many staff from outsourcing companies have left to create their own companies, or have senior positions in existing game companies. They have led the industrialization of the gaming field throughout China. They look at companies like Ubisoft, which they have worked with in the past, and started to create those same production processes. They’re also standardizing developer tools, using Unreal Engine in the case of Black Myth, or Unity in the case of Genshin Impact. Genshin Impact was one of those first games where we saw the streamlined production process for a cross-platform title, where they could create a large open-world game. They were able to put out content on a regular basis, and it was all industrialized into this production process that you would see from a normal mobile or AAA game developer in the West. We are getting to the point now with Black Myth: Wukong that Chinese game developers are starting to give Western, Japanese, and other overseas AAA developers a run for their money.

24:39

Aladin: How is the future looking for Black Myth and the Chinese gaming industry?

Daniel: There is a DLC expansion plan for the game, so we can expect that next year, which will probably give it a second wind of sales. I think one interesting point is that there is a swell of developers now focusing more on PC and console games and the core gameplay experience, not just for the Chinese market and building games based on Chinese cultural IP or stories, but globally, where there’s a large market. Even Tencent, which traditionally has focused on free-to-play mobile games, has now realized that there is money to be made. Their LA studio is developing a game called Last Sentinel, a single-player premium game for the console market.

Another thing worth noting is that even though China’s games market is still growing, it’s not growing as fast as it once was five or 10 years ago. So, a lot of these developers are looking to the overseas market, where Call of Duty sells tens of millions of copies every year. It’s a very lucrative market outside China, and Black Myth: Wukong is the proof of concept. Not to mention IP expansion and trans-media kind of ways of targeting gamers.

30:59

Aladin: Are there any other insights you want to add regarding the future?

Jesse: I would say check out some of the smaller games from smaller studios. A lot of these indie studios may work for four or five years on a game, and it gets buried under recommendation algorithms. If you dig, there’s a lot of fantastic work on the smaller end. So, if you’re curious about gaming in China, some of the most innovative and interesting stuff is happening in the indie scene.

Lundy: We felt like the whole Chinese gaming industry was getting into its winter, but Wukong has brought sunshine from the spring. We now know that many players in China want to consume this kind of game, which gives me confidence that the future of the Chinese gaming industry will be better.