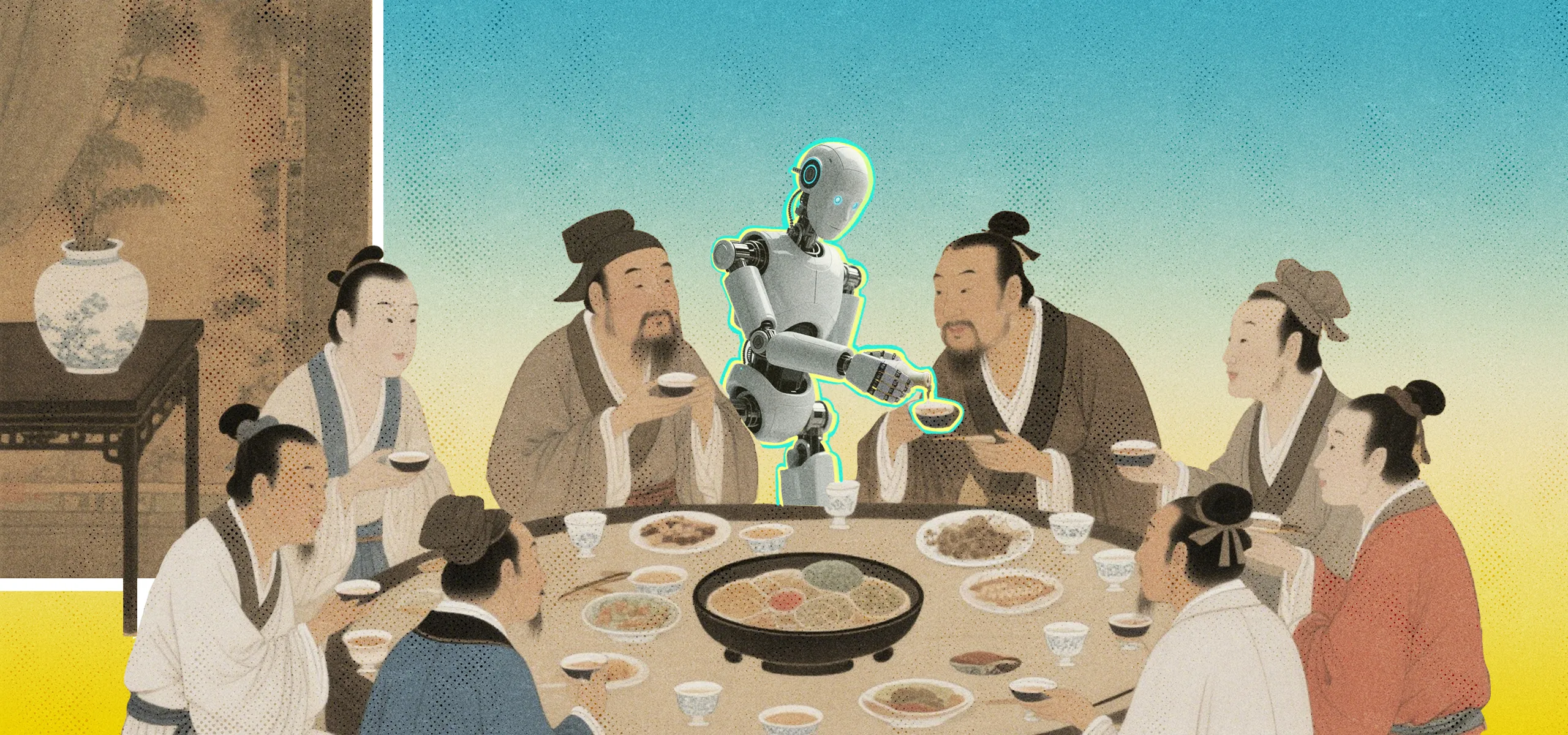

From pedestrian wheelbarrows imbued with mystical powers to mechanical beings that poured wine for Tang dynasty courtiers, ancient China birthed mechanical wonders that blurred the line between craft and myth

This year’s Spring Festival Gala, the annual live variety show that is the world’s most watched televised event, featured an eye-catching program: Sixteen humanoid robots, dressed in Northeastern-style floral jackets and holding colorfully embroidered handkerchiefs, dancing in perfect synchronicity alongside human counterparts. Directed by the renowned director Zhang Yimou, this program made humanoid robots an internet sensation overnight. But in fact, creating robots with human-like capabilities is not a recent dream, as Chinese classics are filled with stories of skilled craftsmen using their creativity to make astonishing mechanical works. And yet at the same time, traditional Chinese philosophy also chastised these inventors as disruptors of the natural order who should be punished. As a result, the history of mechanical figures—early visions of modern robots—in China is a fusion of reality and magic.

In ancient Chinese, the term closest to “humanoid robot” is 俑 (yǒng)—wooden figurines with simple moving mechanisms, commonly used as burial objects as early as the 8th century BCE. Ancient technology flourished during this period, with new developments in iron smelting, dam construction, and astronomical observations. States were constantly at war, prompting the birth of military inventions such as the crossbow and siege ladder. Along with this scientific progress, references to human-like moving figures and puppet-like machines appear frequently in historical texts in ancient China, often as entertainment. Yet it was often their magical qualities that captivated writers, who marveled at their performances but provided vague or no accounts of how they worked.

Read more about science and technology in ancient China:

- Objects that Flew over China’s Skies (In Ancient Times)

- In Ancient China, Mars Spelled Doom

- Ancient Ways to Beat the Summer Heat

China’s first robotic imagination was set in this time in the form of a fable from the 3rd-century Daoist classic Liezi (《列子》) : King Mu of Zhou encountered a skillful craftsman known as Yan Shi, who presented him with a mysterious human-like figure with astonishing lifelike behavior—when its cheeks were pressed, the puppet would sing, and when its hand was held, it would dance in a series of exquisite movements. Just as the performance was ending, the puppet flirtatiously winked at the king’s concubines. King Mu was furious and ordered Yan Shi’s execution.

To save himself, the craftsman quickly disassembled the puppet, exposing its internal structure made of wood and leather, joined with resins and colored with pigments. A closer examination revealed a full set of handmade organs from the heart, lungs, liver, to the intestines. When its heart was removed, the robot was not able to talk, and when its kidneys were removed, it stopped walking. Only then did King Mu cool off and exclaim: “Can human skill truly match the work of Nature itself?”

Today, the tale of Yan Shi is widely regarded as ancient China’s earliest work of science fiction, envisioning a bio-robot that might even possess human emotions.

By the birth of imperial China with the Qin dynasty (221 – 206 BCE), it’s clear that mechanical technology had reached a complex level. After overthrowing the Qin, Liu Bang (刘邦), founder of the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 25 CE), discovered a palace ensemble comprised of bronze figures in the treasury, according to Miscellaneous Records of the Western Capital (《西京杂记》). The 70-centimeter figures had copper pipes beneath them, some of which contained a finger-thick rope. Blowing into one pipe and twisting the rope made bronze figures’ instruments play, producing music like real musicians.

By the 3rd century, according to The Records of the Three Kingdoms (《三国志》), the emperor enjoyed water-powered figures with gears—acrobats that could toss balls, wield swords, and climb ropes. Mechanical puppet shows like these evolved through history into more elaborate versions enjoyed by the common people by the 12th century. Scholar Meng Yuanlao (孟元老) described one such performance in his memoir: a boat with pavilions from which puppets emerged to perform fishing and other activities to music.

Even more marvelous accounts of “robots” appear in the Tang dynasty (618 – 907) book The Anecdotes of the Emperors, Ministers, and Common Men (《朝野佥载》). Yang Wulian (杨务廉), a Tang dynasty engineer, was rumored to have invented a “begging robot.” The wooden monk held a bowl for money, and when it filled with coins, a mechanism made it say, “Alms!“ Eager to hear it speak, people helped Yang earn thousands in a day. Another anecdote tells of a county magistrate at the same time from Luoyang named Yin Wenliang (殷文亮), who created “wine-pouring robots.” These splendidly dressed wooden figures served and toasted guests. If anyone failed to finish their drink, the figures would sing and play music to urge them on.

Curious tales aside, there was no shortage of functional machinery designed to mimic human or animal movements and ease daily burdens. But due to limited records and scientific understanding, few made a substantial impact on history.

One such example is the legendary invention of Zhuge Liang (诸葛亮), a renowned strategist of the 2nd and 3rd centuries: the “wooden oxen and gliding horse (木牛流马),” used to transport grain to the battlefield. While its invention was mentioned in several official historical records—from the Records of the Three Kingdoms to the Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government (《资治通鉴》)—the details of these machines remain elusive. Its vivid name, on the other hand, inspired many wild speculations. The 6th-century Book of Qi of the Southern Dynasties (《南齐书》) described them as automated machines that cost no energy: “…that were powered neither by the wind nor water, and the wooden oxen and gliding horse carried loads without need of man’s physical efforts.” Generations of grassroots inventors have attempted to replicate them, even today. In fact, ancient engineers since the 10th century generally believed that the “wooden oxen and gliding horse” referred to a single-wheeled cart with two handles, allowing one person to transport ample food over the rugged, mountainous terrain.

Water-powered clocks featuring moving human figures were another major kind of automated device in ancient China. According to the History of Song (《宋史》), astronomers Su Song (苏颂) and Han Gonglian (韩公廉) invented the hydraulic astronomical clock, which integrated astronomical observation with automatic time-reporting. Named the Astronomical Clock Tower, this 12-meter-tall timekeeping device consisted of five stories with 162 automated puppets reporting time intervals—from 15-minute segments to full two-hour periods—using bells, gongs, drums, and plaques. Built for accuracy far beyond its era, the device was lost in war in the 13th century. Luckily, Su Song left a design manual, titled Essentials of the New Instruments (《新仪象法要》). In 1958, based on the book, archaeologist Wang Zhenduo (王振铎) was able to rebuild a model of the machine. Today, various replicas can be found in science museums across the country.

By the 16th century, European technologies and thoughts had made their way to China, giving rise to pioneer scholars such as Wang Zhi (王徵), one of the first Chinese intellectuals to explore Western science. In 1627, he co-authored the book Diagrams and Explanations of the Wonderful Machines of the Far West (《远西奇器图说》) with Jesuit missionary Johann Schreck. Wang also invented various wind or water power automated farming figures using the mechanical technologies he learned from western works.

But despite centuries of world-leading scientific and technological achievements, ancient China never experienced a scientific revolution like Europe’s, nor did it begin to develop—or even imagine—more advanced forms of robotics during that period.

In his pioneering work, Science and Civilisation in China, British scholar Joseph Needham proposed, among other reasons, that Confucianism and Daoism, two major philosophies in ancient China, may have been an important cultural factor hindering scientific exploration. The former emphasizes moral order and social harmony, while the latter focuses on harmony with nature and non-intervention.

One doesn’t have to look far to find striking quotes from both schools of thought reflecting their dismissive attitude toward technology, often viewing it as mere trickery or frivolous craftsmanship, unworthy of serious intellectual pursuit. Both also seemed to believe that technological exploration could potentially destabilize the state. For instance, the Daoist classic Tao Te Ching (《道德经》) criticizes that “when the people have many sharp tools, the nation will grow chaotic; when people have many clever tricks, strange artifacts will proliferate.” The Confucian classic Book of Rites (《礼记》) goes even further, stating: “Those who create licentious music, strange clothing, bizarre skills, and peculiar devices to confuse the masses shall be put to death.”

By the first decades of the 20th century, it was this rejection of technology and science that partly inspired Chinese revolutionary figures like Chen Duxiu (陈独秀) and Li Dazhao (李大钊) to advocate for a wholesale change in Chinese politics, thought, and life. Indeed, an embrace of “Mr. Science” was one of the rallying calls for the New Culture Movement, and a message that continued to be important throughout China’s tumultuous 20th century.

At the turn of the new millennium, China unveiled its first bipedal humanoid robot, “Xianxingzhe” (or “Pioneer”), kicking off a rapid phase of robotic development that would eventually bring dancing robots to the Spring Festival Gala stage. But one can’t help but wonder—if some of the brilliant robotic ideas from ancient China had survived and evolved, what kind of future might have unfolded?