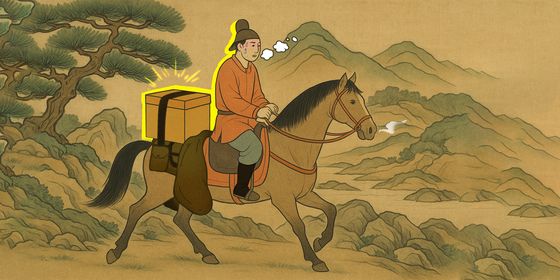

How a Song dynasty goddess continues to protect—from ancient seafarers on the maritime silk road to modern exporters in today’s global trade war

In China, the celestial being one is most likely to encounter mid-flight isn’t a mythical winged creature, but Mazu (妈祖), the thousand-year-old goddess of seafarers. On March 29, two Mazu statues boarded Xiamen Airlines Flight MF881 at Gaoqi International Airport, buckled in for their 28th annual cultural exchange trip to Taiwan.

Chen Yang, a Hainan-based interior designer who was onboard the Mazu flight, tells TWOC that sharing a cabin with the deity was an unforgettable spiritual experience. “The whole flight carried this sacred energy—it’s hard to explain until you’ve experienced it yourself. I spent the entire journey hoping Mazu would bless our family with health and peace for the year ahead,” said the 32-year-old, his voice filled with awe and reverence. He asked his grandmother for advice before taking a photo of the statues, worried it might be disrespectful to the goddess.

Every year, lucky aviation passengers like Chen could spot the sea goddess on board. She gets her own seat in first class and a boarding pass under her mortal name Lin Mo (林默), complete with ID number 350321096003237001. But far from an airline PR campaign, the journey of the Mazu statues embodies a millennium-old tradition connecting coastal communities from Fujian fishing villages to Singapore’s megaports.

Read more about Chinese gods:

- Ne Zha: From Myth to Cultural Icon

- Sculpting Divinity: The Artist Creating Gods from Ancient Folklore

- On Her Porcelain Throne: How a Little-Known “Toilet Goddess” Became an Icon for Powerless Women

Mazu, literally meaning the “motherly ancestor,” is also venerated as the Grand Princess, the Heavenly Empress, and the Heavenly Mother. Worshipped as a sea goddess since the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), she has long been a guardian of coastal communities. In 2009, UNESCO recognized “Mazu belief and customs” as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, for its deep integration into the lives of coastal Chinese and their descendants. Mazu’s Xiamen airline flight was one of many planned trips for the goddess this year, as the statues keep a hectic travel schedule of “peace patrols,” where devotees, both domestically and among the overseas Chinese diaspora, invite the goddess to tour their surroundings, ward off evil spirits, and pray for peace. Today, according to a 2020 report by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and China Tourism News, there are over 10,000 Mazu temples worldwide, spanning nearly 50 countries and regions across five continents, with more than 200 million followers.

Mazu’s image evolved from her mortal origins as Lin Mo, the daughter of a coastal official born on lunar March 23, 960, on Meizhou Island in Putian, Fujian, during the early Song dynasty. Since birth, Lin has displayed extraordinary qualities. Legend has it that she never cried within the first month after birth, hence earning the nickname Mo Niang, meaning silent girl. Blessed with intelligence and compassion from a young age, she was noted for her knowledge in astronomy, skills of navigation, and a heart eager to help troubled fishermen in deep waters, gaining widespread popularity and admiration.

Lin’s talents extended beyond the sea—she also practiced medicine, a respected field linked to shamans and prophetic intellectuals. This is reflected in the Records of Renovating Shunji Temple at Shengdun Ancestral Temple (《圣墩祖庙重建顺济庙记》) written in 1150: “Especially miraculous is the power of the goddess, revered by the people and hailed as a celestial maiden. She began with shamanic practices and was later gifted with foresight into human fortunes and misfortunes.”

At the age of 28, Lin tragically lost her life while rescuing a distressed ship at sea. In honor of her selfless heroism, a temple was built atop Meifeng Peak, where she had once guided navigators. This became the world’s first temple dedicated to the goddess, known as the Mazu Ancestral Temple. After her death, tales of her divine intervention continued, with stories of her walking on water to rescue ships and protect maritime trade.

As time passed, Mazu began to be referred to as the “Divine Woman of Virtue” or the “Dragon Lady,” and her divine status gradually increased. The imperial court’s reverence for this sea goddess was closely intertwined with the prosperity of overseas trade. During the 12th and 13th centuries, limited land and explosive population growth created a need for overseas trade and maritime expeditions. However, ancient shipbuilding and navigation technologies were still an inexact science, and seafaring—particularly long-distance voyages—was a perilous gamble. As Zhen Dexiu (真德秀), a 13th-century governor of the Fujian port city of Quanzhou, put it: “Trading afloat the sea, risking life for profit.” In the face of such dangers, sailors would pray for divine protection at sea god temples before setting out. Many temples were built along the coasts, especially at port terminals, with Mazu temples being the most common.

In contrast to the Western seafaring myths centered on conquest and colonization, the Mazu belief embodies China’s philosophy of peaceful maritime engagement. Major maritime events, such as the Song dynasty’s diplomatic missions to Goryeo (present-day Korean Peninsula), the Yuan dynasty’s (1206 – 1368) maritime shipping operations, and the Ming dynasty’s (1368 – 1644) treasure voyages led by Admiral Zheng He (郑和), all carry legends of Mazu’s blessings. Zheng He himself worshipped at Meizhou’s Mazu temple, enlisted Fujianese shipbuilders and merchants, and petitioned the imperial court to elevate Mazu’s status, helping to spread her cultural influence throughout his voyages.

By the 19th century, Mazu had been bestowed with an elaborate 64-character imperial title, hailing her as the “Guardian of the Nation,” “Promoter of Prosperity,” “Defender of Waterways,” and “Guarantor of Peace,” among many other honors—achieving the highest status of any female deity in imperial China. With the elevation of her title, places of worship dedicated to Mazu were upgraded from simple “shrines (祠)” and ”temples (庙)” to grand “palaces (宫)” and “parks (观),” featuring increasingly elaborate architecture.

Today, in overseas Chinese communities, the Heavenly Empress Temple often serves as a hub for cultural and community activities, with Mazu worship helping to build connections between the Chinese diaspora and local residents. A highlight of Mazu folk traditions is her birthday celebration on the 23rd day of the third lunar month. On this day, temples around the world host grand ceremonies featuring offerings of flowers, fruits, and brocade, chants of blessings, and traditional rituals such as the “three kneelings and nine kowtows.” In Batangas, Philippines, the Mazu birthday celebration preserves traditions from the ancestral temple in Meizhou while incorporating Filipino elements, such as serving Chinese-Filipino cuisine. At the Sam Poo Kong Temple in Semarang, Indonesia, the celebration blends the traditional Lantern Festival with a Mazu Parade, where Indonesian Chinese carry the Mazu statue and chant prayers to ward off potential illnesses for the year.

On the Chinese mainland, Mazu’s influence goes beyond mere religious devotion—she is now deeply woven into everyday life and even local governance. When faced with major life decisions or personal challenges, many Fujianese visit Mazu temples to seek her guidance and approval through traditional rituals. For 29-year-old Liu Zhizhi—a native of Shanwei, in eastern Guangdong province, who accepted the interview under a pseudonym—Mazu’s presence is as real as the shipping containers she oversees in her e-commerce logistics job. “Last monsoon season,” she recalls, “a shipment was delayed by storm until my grandmother reminded me to light incense at our home altar. The next morning, the seas calmed and our goods arrived on time.”

Even actress Liu Tao, who portrayed the goddess in the 2012 TV series Mazu, sought her blessing before accepting the role. The award-winning show, broadcast on state-run CCTV, became a massive hit, setting a viewership record for mythological dramas with a peak rating of 5.1 percent.

Fujian’s “Mazu Mediation Room,” established in 2019 by 13 municipal departments, creatively leverages spiritual reverence to resolve neighborhood disputes. “Never lie before Mazu. That’s every Fujianese’s bottom line,” quips a popular online meme. Judicial director Yang Yang confirms its effectiveness to the newspaper Southern Weekly: “If someone shows signs of lying during mediation, we’ll have them visit the Mazu temple first to instill a sense of reverence and accountability...Once the mood is right, the mediation would go more smoothly—after all, no one wants to go against Mazu.”

On the lifestyle app RedNote, tongue-in-cheek posts about “Mazu Logistics (妈祖物流)” also playfully credit Fujianese traders’ supply-chain and trade route prowess to divine intervention—especially amid escalating tariff wars. When Changhua county in central Taiwan welcomed the Mazu statues on April 5, just days after the US announced 32 percent tariffs on manufactured goods from the island, local officials expressed confidence that, with Mazu’s blessings, Taiwan could weather the impact and navigate the turbulence of a global trade war. Logistics manager Liu shares that belief, emphasizing the enduring nature of Mazu’s tradition: “Whether facing Song dynasty storms or modern trade headwinds, we’ve always believed that open seas bring shared prosperity.”