With the 2025 World Expo underway, take a look back at China’s long-standing presence and key milestones at the global fair

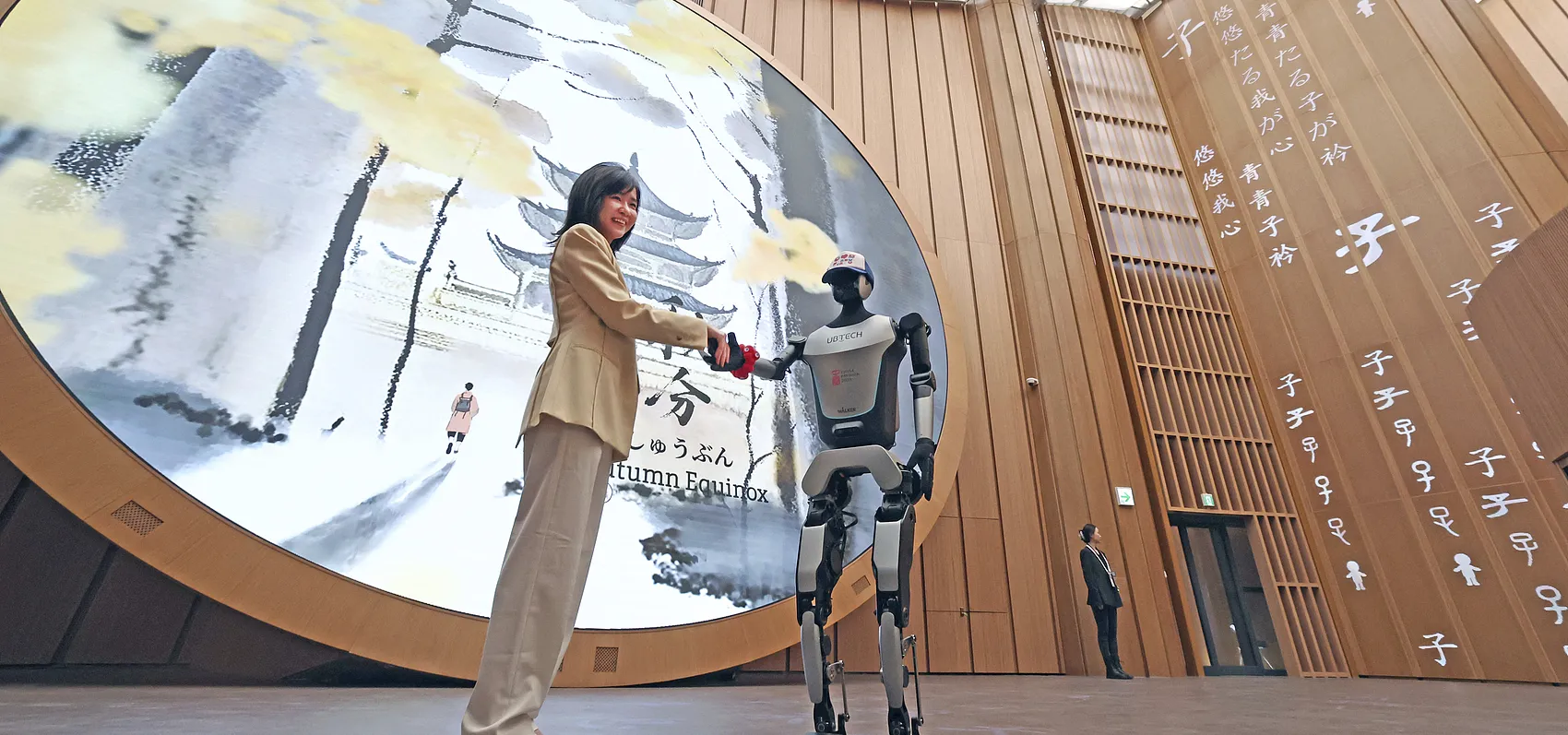

The World Expo kicked off last Sunday in Osaka, Japan, launching a six-month celebration under the theme “Designing Future Society for Our Lives.” With participation from over 160 countries, regions, and international organizations, the event showcases cutting-edge achievements in technology, culture, and cuisine.

This year, under the banner of “Building a Community of Life for Man and Nature,” the China Pavilion—designed to resemble an unfurled bamboo slip or calligraphy scroll—spotlights green technologies and lunar soil samples from both the near side and far side of the Moon.

Many have also taken to social media to reminisce about the 2010 Shanghai Expo—a landmark event that showcased a modern, forward-looking China on a global stage. But China’s ties to the World Expo go back much further than Haibao and Shanghai. In fact, the country has been an active participant since the 19th century. At the very first World Expo in London in 1851, a Chinese merchant won a gold medal for his silk.

Here are some of the most fascinating moments in China’s Expo history—from traditional calligraphy to artificial blood serums.

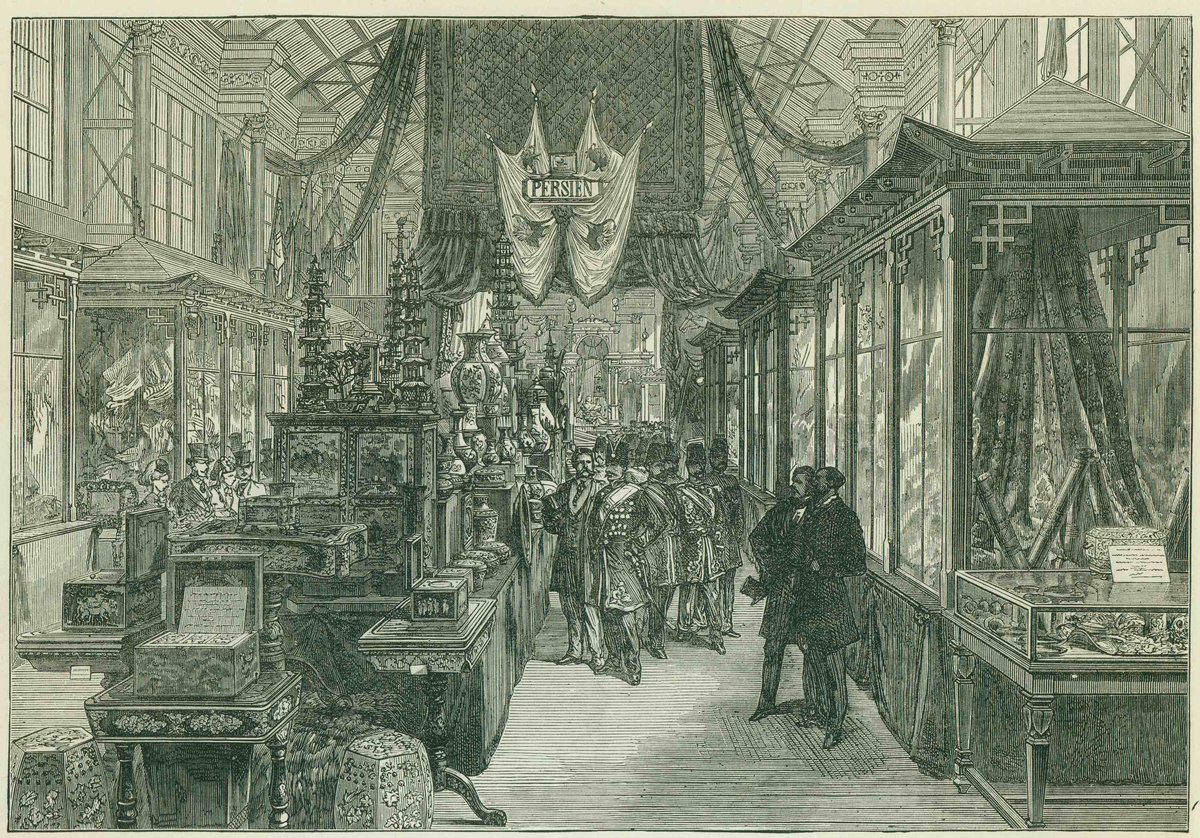

Paris, 1867

With almost 10 million visitors, the Exposition Universelle was considered a massive success, hosting more than 50,000 exhibitors. Many of the post-impressionists, like Van Gogh, were said to have been greatly impressed and inspired by the Asian arts they saw here.

At the Chinese Theater, traditional arts were on display—acrobats, sword-swallowing magicians, and brightly dressed Cantonese opera performers. The entrance fee? 1.5 francs.

Vienna, 1873

At the Weltausstellung 1873, the first World Exposition to be held in a German-speaking country, awards were given to engines, elevators, and gas lamps. But while the age of electricity has replaced the age of steam, China’s exhibition focused on what had changed little over the years: traditional herbs, porcelain and silk. Miniature towers (文昌塔)—inspirational feng shui ornaments for scholar’s studies—were also on display. A Chinese teahouse offered visitors a chance to experience the leisure life of traditional China.

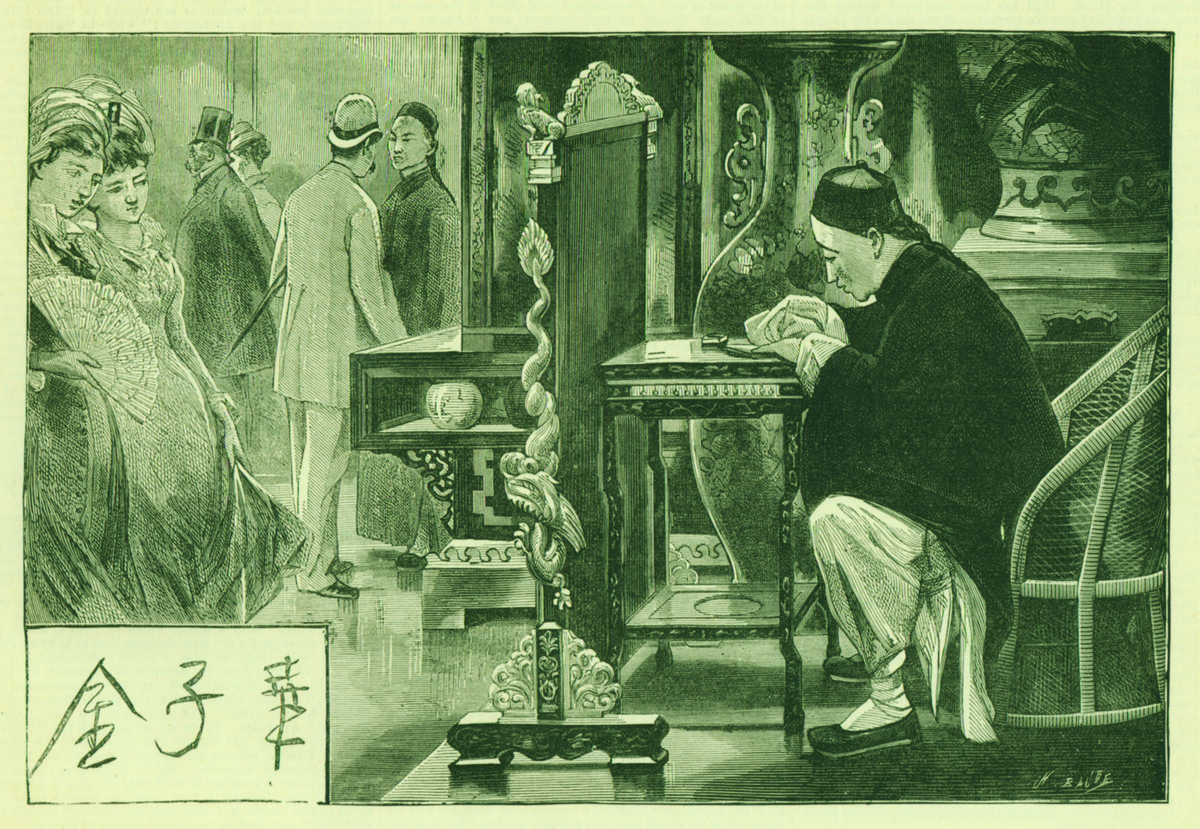

Paris, 1878

Spanning a remarkable 66 acres, drawing 13 million visitors, and offering such jaw-dropping displays as the Statue of Liberty’s head (the body had not yet been built), the third Exposition Universelle offered much to gape at. But it was the smaller events, the more personal, that left a lasting impression. The Illustrated London News ran this image of an unnamed calligrapher at the Chinese pavilion. He was reported as having an impressive amount of calmness and self-control, diligently writing throughout the day. He drew characters with a weed pen, from right to left, and—despite the large crowd—was not distracted at all, not even by a pack of curious Mademoiselles. Wearing a silk cloak and an official hat, he was clean-shaven, and his pigtail was reported to have been “well-braided.”

Chicago, 1893

Held to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ arrival in the New World, The Chicago World’s Fair drew 27 million people, and focused heavily on the power of electricity, introducing the world to Nikola Tesla, neon lights, and hamburgers. But it was also a chance for China to reveal more of its rarely-seen traditional culture. On the left, a model poses in Chinese costume, but more exciting to many was the cross-dressing actor on the right. In the late 1800s, women were not allowed to perform in operas, so men not only had to dress up in drag, but they also had to sing in falsetto.

Paris, 1900

The Exposition Universelle of 1900 drew a crowd of over 50 million to Paris, and talking films and escalators both made their debuts. It was also where Rudolf Diesel premiered his diesel engine, fueled by peanut oil. The Supplement Illustre Du Petit Journal published this illustration of the China Pavilion, where sedans, rickshaws, and porcelains, as well as ornate traditional architecture, are showcased.

St. Louis, 1904

To commemorate the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase, the 1904 Expo was hosted by America and held in St. Louis. Ragtime music was hugely popular at the time; Scott Joplin even wrote a song for the occasion called “The Cascades.” The famous Apache war chief Geronimo was present, accepting visitors in a traditional Apache teepee, which was draped in animal hide. But one American was particularly fascinated by the Chinese pavilion.

“There is a temple,” he wrote, “where all the religious rituals and signs [are explained]. There is a market displaying crafts of carpenters, painters, silk weavers and ivory sculptors. The garden is exotic. Everything is shipped here directly from the native land. It is like a pleasant, temporary home.”

But the 1904 Expo wasn’t just about Chinese entertainment—the Shanghai Tea and Porcelain Company also inked a monumental deal with the American Blank Company; in addition to buying 40,000 tons of tea, the Blank Company agreed to distribute Shanghai tea across the United States.

San Francisco, 1915

The Expo held in San Francisco in 1915 celebrated the completion of the Panama Canal—a boon to international trade. The Liberty Bell was on display, and the first steam locomotive was also shown. This expo also meant a great deal to the newly formed Republic of China

(1912 – 1949).

America was the first colonial power to accept the Republic of China as an official entity, and the 1915 Expo was the debut of the new government. Chinese and American flags were hoisted together outside of the Chinese pavilion, and an American orchestra, positioned next to the Orchestra of Shanghai, played the Chinese national anthem at the time. The Orchestra of Shanghai also performed beautifully and won a gold medal.

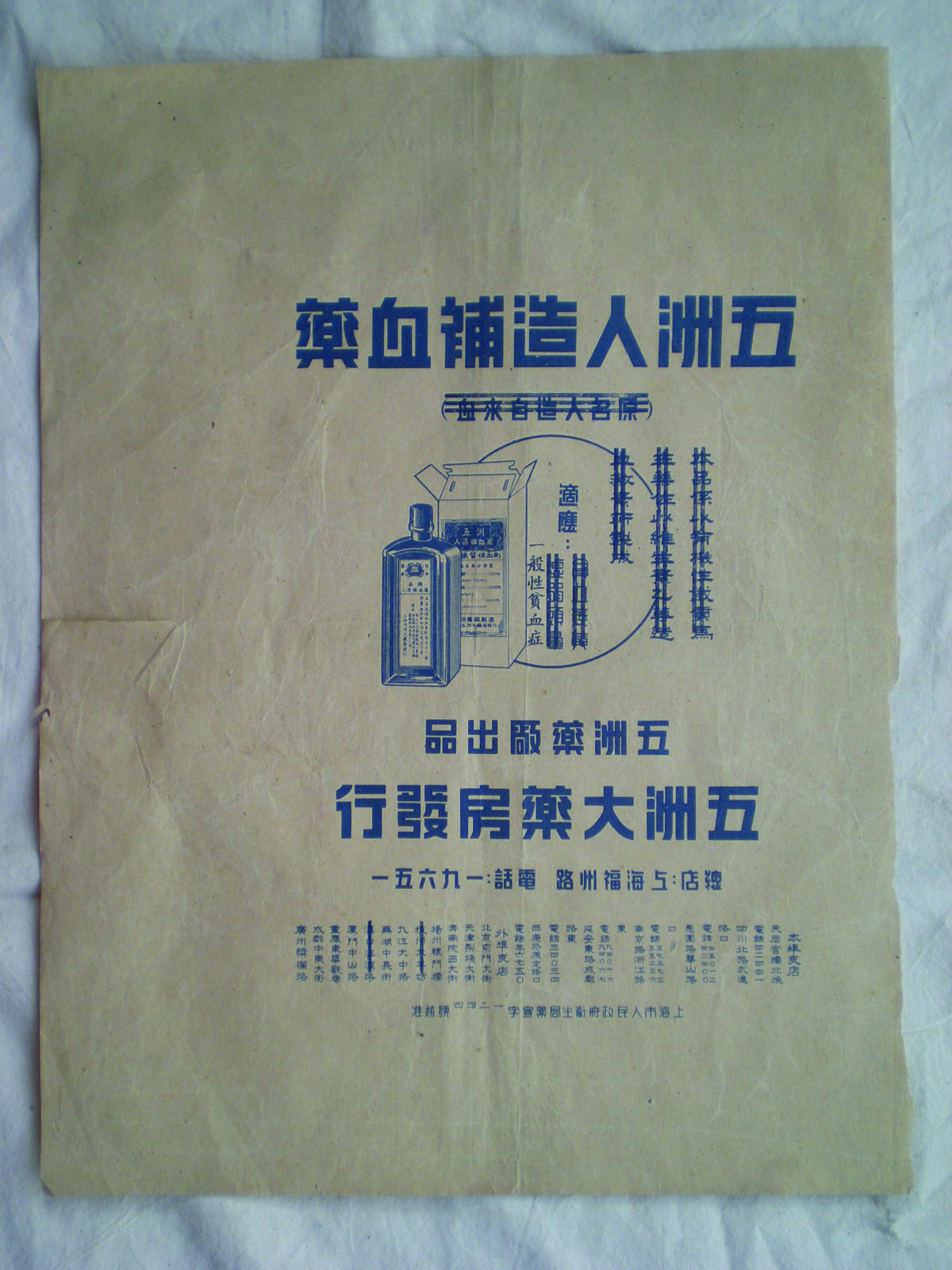

Altogether, China won 1,211 awards at the 1915 Expo. Among the prize-winning goods displayed was a red liquid, the Wuzhou Pharmacy’s cure for the then-common illness, anemia. The inventor had named it “Boluode (博罗德),” a phonetic translation of the English word, “blood.”

Chicago, 1933

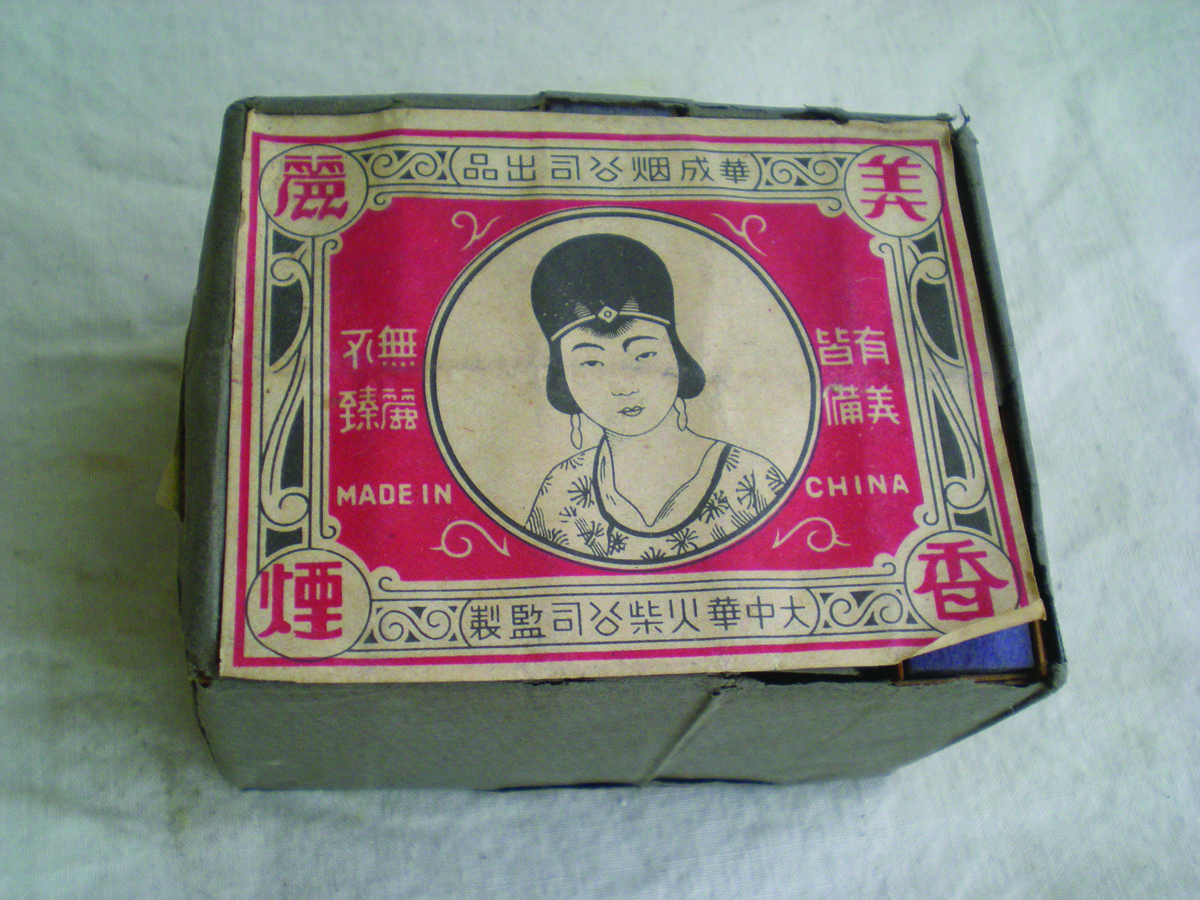

Chicago hosted the World Expo in 1933 with the theme “A Century of Progress.” The German airship, the Graf Zeppelin, flew overseas and timed its arrival to correspond with the opening of the Expo. China’s pavilion displayed booths from many provinces, highlighting the diversity of its people and inventions. One of the country’s award-winning products was a new brand of Shanghai-produced matches. In China, matches had always been called yanghuo (洋火, foreign fire)—because they were invariably imported. But this award-winning home-grown brand had a new name: Da Zhong Hua, “Mighty China.”

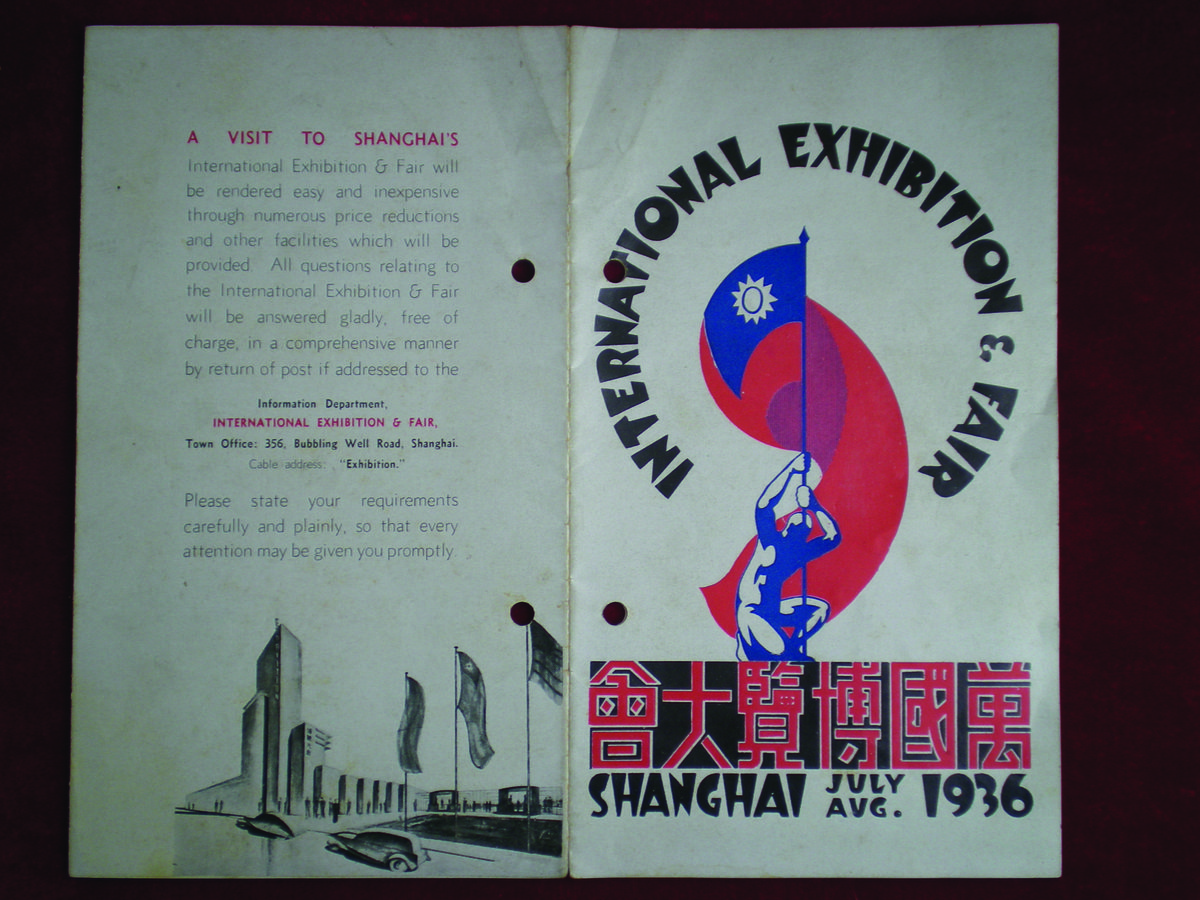

Shanghai, 1936

Shanghai was going to host the Expo in 1936. Plans had been drawn, the Huangpu River location had been settled, and flyers had even been printed. But the Expo was ultimately canceled due to the advancing Japanese invasion.

Shanghai, 2010

Then, 74 years later, in 2010—after political revolutions, reforms, and decades of incredible development—Shanghai welcomed over 240 countries and international organizations, attracting 70 million visits from across the world within the 184-day World Expo.

The event showcased over 20,000 cultural exhibits, including the animated version of “The Riverside Scene at Qingming Festival,” which has enlarged the original work by 30 times. The exhibit brought the prosperous scene of the capital of the Northern Song dynasty into the 21st century.

The mascot of Expo 2010, Haibao, literally “treasure of the sea,” featuring the Chinese character “人 (person)” as its core concept, was noted for its cute and playful design.

Aligned with the call for sustainable energy, more than 1,300 new energy vehicles (NEVs) were put into operation, serving 125 million passenger trips, cementing the city as one of the leading positions of NEVs in the country.

Special thanks to Tong Bingxue, Expo collector, founder of the online “China Photography Museum,” and author of the book, China’s Image at the World Expos, published by the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press. Special thanks, also, to Zhang Jianming, of the Old Shanghai Teahouse and Museum, and publisher of the book Old Shanghai, Old Expo. The images here were originally published in their two books, unless otherwise credited.

This is a story from our archives. It was published originally published in 2010 and has been edited and republished. Check out our subscription plans that will give you access to more great stories!