What was once a banned pastime in the 1980s has transformed into a nationwide cultural movement—filled with joy, competition, and camaraderie

The old lady came alone and sat alone, smoking a Zhongnanhai-brand cigarette. Her skin was uncannily white, the aftermath of a bad bout of vitiligo, and her grey hair was dyed a yellowish brown. Her eyes looked listless in their walnut-like sockets, and her body was shrunken. Her pink shirt dangled—old age seemed to have taken away all the flesh. When she finished her cigarette, she stood up, a small person about the size of a 10-year-old boy.

She held her hand out to a younger woman and then she started to dance.

Houhai’s lakeside Lotus Market is one of the oldest dancing locations in Beijing. It sits in the center of the city, and for generations has been a place that locals swarm to for entertainment. The last 10 years have seen great change, as it has become a commercial bar area, but every evening after 8:30, the local dancers return.

Read more about recent history in China:

- 40 Years of Kissing in Chinese Cinema and Society

- 30 Years of Backpacking in Revolution and Leisure

- 30 Years of Choosing College Majors in China

This old lady danced a man’s part. The majority of the dancers there were women, so it was common for women to partner up. Her eyes started to glisten as if something inside had lit up. Her face shifted into a childlike grin.

Most of the dancers here have been coming for decades, but they treated this 75-year-old with reverence. For she was an encyclopedia of jiaoyiwu (交谊舞), or ballroom dancing. She knew it all, could name every dance that existed, and some nearly extinct ones, too.

In China, ballroom dancing seldom happens in ballrooms. Dancers make use of any open ground: squares, parks, the outsides of banks or supermarkets, and even sidewalks. And the dances themselves are different from Western ones, too. Our cha-cha is nothing like the cha-cha you might know, and our rumba is not much more recognizable. The tango developed into the Taiwan Tango and the Hong Kong Tango. Other dances are also named after cities, where they were invented: the Guangzhou cha-cha, the Nanjing sailor’s dance, and the Tianjin jitterbug. But mostly the dances are just named for their rhythm: the fast three (快三 kuài sān), the moderate three (中三 zhōng sān), the slow four (慢四 màn sì) and the just four (平四 píng sì). They danced to popular old Chinese songs like “The Military Harbor’s Night” or to ethnic music.

In most cases, the dances are simplified variations of their Western originals, sometimes with a twist of traditional Chinese dancing. They don’t require much talent or skill, and that’s part of why they’re so popular.

Taking a break, the old lady’s dance partner whispered to me. “When she dances the rumba, her moves are straight from that 1950s movie. Nobody can dance like that today.”

She was talking about A-Lan, who danced as a beautiful spy in the 1958 movie Intrepid Hero (《英雄虎胆》). The movie would be forgotten today were it not for A-Lan’s brief appearances, during which she danced a half-minute of rumba. These 30 seconds are as memorable as Uma Thurman’s famous dance scene in the American crime film Pulp Fiction (1994). They introduced the dance to millions.

The 75-year-old lady didn’t like to talk, unless it was about how to dance. She only told me that she had been dancing for 50 years. The first dance she learnt would have been A-Lan’s rumba.

Yi Chan was a tall woman in her 50s. She was large, but she must have been beautiful when she was younger. For half an hour she stood at the rim of the circle and just watched.

“I just came to have a look,” she said. “I don’t want to dance tonight.” Indeed, she was wearing a tight ankle-length skirt and heels. “I haven’t danced for 20 years. This is the first time I’ve come back.”

This was the place where Yi Chan first saw people dancing jiaoyiwu. It was in the early 1980s, and she was petrified by what she saw. It seemed almost libertine. But when her workers’ union encouraged employees to learn to dance, she fell in love with it.

“My parents and my husband objected strongly. It was considered inappropriate for the wife to dance if the husband didn’t.”

So why didn’t he?

“The workers’ union hired professional dancers to train the workers, but he wouldn’t go to the lessons. He was hopelessly stubborn, and he wouldn’t let me go to dance balls either. After one big fight, I just gave up. I had friends who divorced over dancing, and I didn’t want to end up like them.”

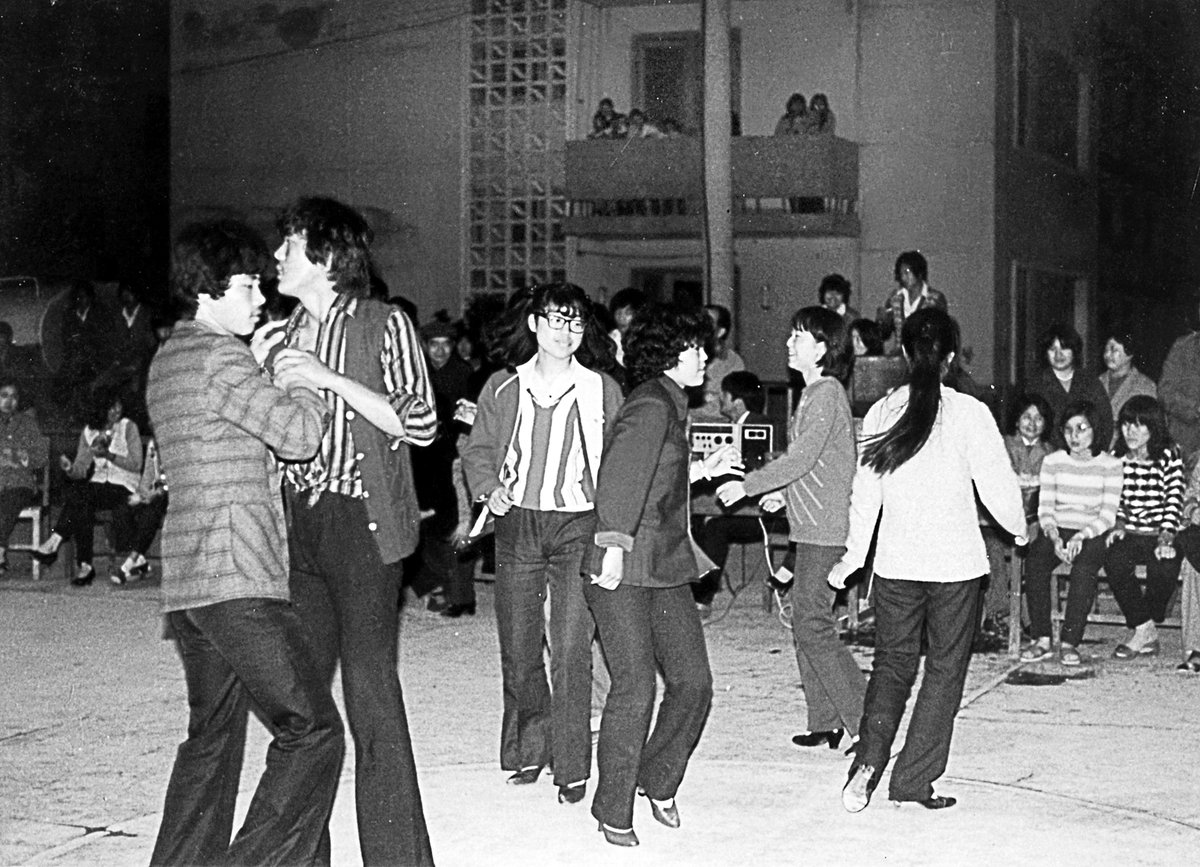

In the 1980s, it wasn’t just husbands who were stopping their wives from dancing. Just as dancing was becoming popular, a Public Security Department and Cultural Department ban shut down all privately-owned ballrooms. Dancing in public was also banned—the large crowds that collected to watch were considered a threat. In 1983, a series of anti-crime campaigns called yanda (literally, “Hard Strikes”) were launched. A middle-aged Xi’an bachelorette named Ma Yanqin was executed because she loved dancing, and her dance partners totaled over 300. (There were also accusations that she did more than dance with somewhere between one and three of them—the men were also executed.) Any hint of a spring for jiaoyiwu in these early 1980s turned into a very dark winter, instead.

But even that didn’t kill jiaoyiwu. In 1984, the ban was rescinded, and dancing—while still regulated—saw an upsurge in popularity. Fifty-six private ballrooms opened in Tianjin that year, and delegations were sent from around the country to study how Tianjin handled the sudden emergence of ballrooms and dancers. That year, the Shanghai Exhibition Hall hosted the first public ballroom dance, marking the revival of commercial dancing in the city after a 20-year hiatus. A year later, the city boasted over 140 dance halls, with enterprises and schools organizing dances. After all, everyone loved dancing.

Now, decades have passed, and so many things have changed. International Ballroom Dance competitions are drawing participants of all ages from across the country. Older adults are embracing ballroom dancing as a means of friendship and exercise. Yi Chan’s husband no longer objects, but poor Yi Chan had new worries.

“I snuck here without telling my son,” she said. “He would make a huge fuss over it, driving me here and having dinner in some nice restaurant. But I just want to watch people dance, and then leave quietly.”

But she didn’t do this. She danced, too.

The dancers are amateurs from a professional’s point of view. “Forget these dances if you’ve learnt any,” Hu Laoshi, a waltz teacher in Wuhan, urged his adult students. “These dances are ugly.”

But he must never have danced with a crowd in a park, where the dancing becomes magic. By day, they are just the tired divorced mothers you pass in the street. Or the businessmen who reek of baijiu from endless toasts with clients and partners. They are migrant women working hard to make a living ironing clothes in a back-alley shop, or balding and bored middle-aged men. But when the night falls and the music is on, they become dancers.

Although they might be uncoordinated, and their joints may be stiff, they dance seriously and passionately. The same joy flows through everyone—the joy that has enabled jiaoyiwu to endure through tumultuous times.

This is a story from our archives: It was originally published in 2010 and has been lightly edited and updated. Be sure to check out our online store for more great stories!