Since graduating from Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts in 2016, Cao Yu has set out to make work that is brazen, subversive, and unflinching, becoming one of China’s most influential young artists in the process

In front of a faded red brick wall, a woman in a black blazer and pants sits on a concrete sink, chest partly exposed, legs spread wide. From between them a broken faucet erupts, ejecting a violent stream of water like a flash of blinding light. The posture blurs the lines between masculine and feminine, and the subject’s intense gaze commands attention, daring viewers to confront her and the explicitly subversive intent behind the image.

This photographic artwork, titled “Dragon Head” (a direct translation of the Chinese for “faucet” or 龙头), is a self-portrait by Chinese artist Cao Yu. Made in 2020, Cao explains that this work was an attempt to assert, “Anyone can transcend all inherent boundaries and create freely, without distinction of gender.”

“The edges of the sink symbolize various inherent limitations in our lives—such as gender, appearance, origins, nationality, and the societal expectations we learn from a young age about what we should or shouldn’t do,” she explains to TWOC. “These frameworks have the power to confine an individual’s entire life. The water from the faucet, however, is no longer confined by the sink’s edges; it has escaped the fate others planned for it. People often say broken faucets should be fixed, much like the way dreamers of change are often labeled rebellious madmen. But as long as the faucet remains ‘unrepaired,’ the water will keep flowing, surging like an unstoppable tsunami, eventually becoming a torrent none of us can predict.”

Discover more contemporary Chinese art:

- Wool and Wounds: How Art Gave a Chinese Mother Her Voice Back

- Beyond the Frame: Shuare Shizhu’s World in Wide Strokes

- Too Rich: Wealth and Peril in Huang Heshan’s City Dreamscapes

Three years after the original work’s creation, Cao imprinted the image on a flag styled after ancient Chinese military banners from the Three Kingdoms period (220 – 280). She then traveled to various places around the world—across nearly 20 cities and regions, from the ancient battlefield of Italy to the snowy Alps in Switzerland and the edge of a mountain cliff in central China—hoisting it as a proclamation for people to forget their intrinsic limitations and create freely. All the while, despite the curious glances from passersby, she encouraged herself with the declaration: “Creativity is everywhere, and I was born to do this!”

“I don’t want my artwork to be confined within the seemingly lofty walls of art museums. I want to spread art like dandelion seeds, scattering it across the world and reaching all corners,” Cao says.

However, some traditions are harder to break than others. The flag, dubbed “Dragon Head · Shanhe Declaration” (shanhe means mountains and rivers in Chinese, referring more generally to the world at large), is Cao’s entry into the recent “Pictures of the Post-80s Generation: Generational Leap” at TANK Shanghai. There, it sits alongside the works of 35 of the most influential Chinese contemporary artists working today.

Born in 1988 in China’s northeastern Liaoning province, Cao’s work now spans a breadth of mediums including video, installation, performance, photography, sculpture, and painting. With her distinctive cross-disciplinary practice, incisive and bold artistic language, and witty and ironic expression, she has emerged as a leading figure among China’s new generation of artists. And while her work has been known to attract controversy at home, that hasn’t stopped, or perhaps is the secret behind, Cao’s formidability.

A prime example is “Fountain” (2015), one of Cao’s earliest works and which she presented during her master’s graduation exhibition at Beijing’s prestigious Central Academy of Fine Arts in 2016. In the 11-plus minute silent video, the camera points directly down Cao’s naked torso, offering a first-person perspective of the milk that she massages from her breasts, spraying upward into the sky before splashing down rapidly, beating against her body until she can’t squeeze out a single drop. Aged 26 at the time and filmed shortly after giving birth, the piece was a direct and powerful response to her ongoing suffering from painful mastitis, while also acknowledging the immense potential, boundless vitality, and explosive force of the female body.

“My body has naturally become a living fountain, and I realized this powerful scene is more real than any fountain in European squares. It originates from the inherent strength of women,” says Cao.

As such, the piece could be regarded as a new, contemporary, feminine take on the fountain, which has a rich historical and aesthetic significance in art, the continuation of this history—from Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ neoclassical depiction of a nude woman languorously pouring water from a ceramic jug in “The Fountain” to Dadaist Marcel Duchamp’s iconic “Fountain” urinal, and later, Bruce Nauman’s irreverent “Self-Portrait as a Fountain.” That, however, didn’t stop the Central Academy of Fine Arts from labeling the work as comprising “pornographic exposure.” Cao was drawn into controversies and received a barrage of harassment online.

Undeterred, Cao doubled down, releasing “The Labourer” two years later in 2017. In the austere, spotlit video, Cao’s bare feet are illuminated as they slowly knead a mound of flour, while urine slowly trickles down her lower legs, binding the mixture—a provocative commentary on womanhood and domesticity. While creating the piece, Cao recalls, “I looked down and saw my reflection in the urine. I felt like I was talking to another version of myself.” In her follow-up piece, “Piss-Take a Look at Yourself” (2023), she plays on the Chinese proverb meaning “take a good look at yourself.” After years of experimentation on how to permanently solidify urine, Cao has finally created a puddle of urine with a mirror-like reflective surface, standing upright.

“Since the inception of this work, controversy has never ceased,” Cao explains. “But the disputes it generates are precisely part of its concept. Though it may seem extreme, it offers people a chance to reflect. I cherish this piece and see its artistic message as a New Year’s blessing—finding a clear sense of self amid chaos feels far more authentic than the usual well-wishes for longevity and prosperity.”

Brash and subversive, Cao’s work is unsurprisingly weighed by critics through the lens of feminism, a tag to which she remains largely indifferent. “Those who interpret my work as ‘feminist’ or any other ‘-ism’ have fallen into a trap. It’s overly simplistic and crude to judge everything by gender—creativity knows no gender. Many media outlets and critics have also framed my work as an ‘offense’ to the audience, but I honestly don’t care at all. Others’ evaluations have no direct bearing on my creative process,” Cao tells TWOC.

Cao’s indifference to external pressures isn’t something innate, but as she explains, the result of a long and ongoing healing process. “When I was born, my father said, ‘The Cao family is out of luck, we had a girl,’” she says. “My family didn’t like girls, so as a child, neither my grandfather nor my father really liked me. But 24 years later, that very sentence, like a stroke of genius, became the perfect starting point for another one of my projects.”

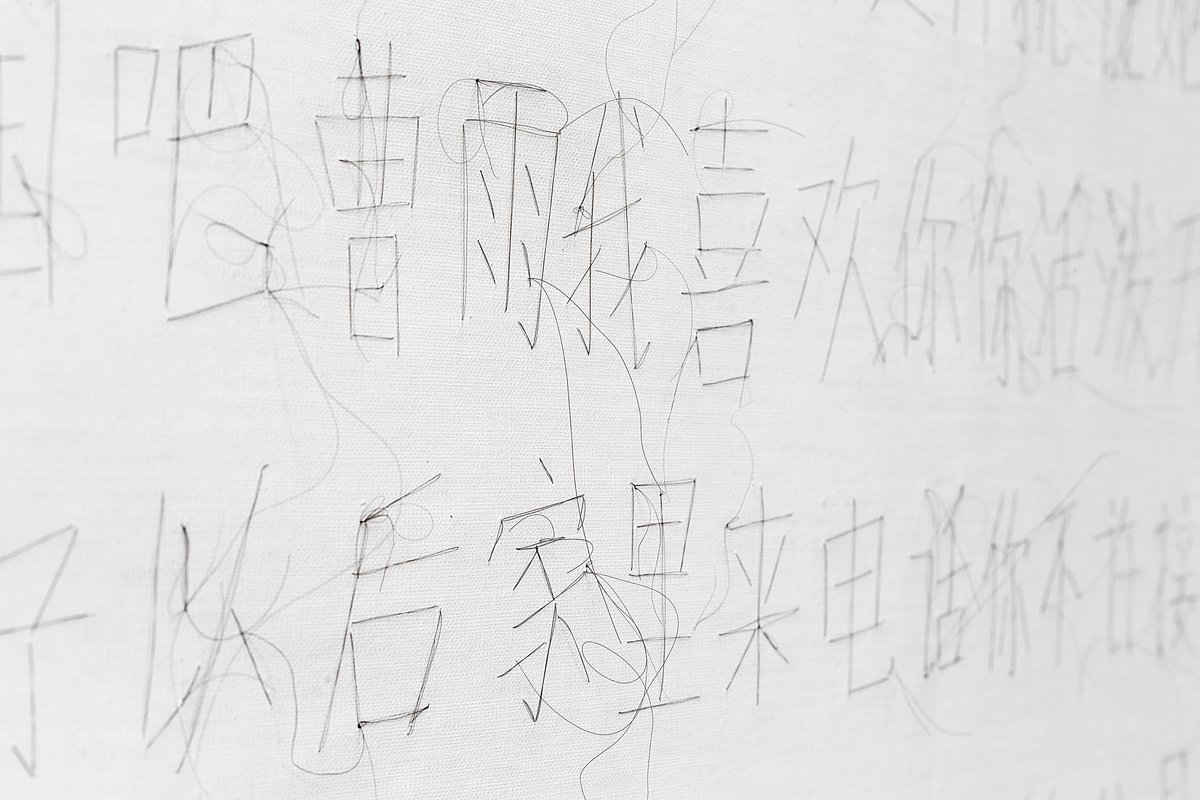

She refers to her ongoing series “Everything is Left Behind,” which started in 2012, and is a direct act of confronting and overcoming this pain. Using her personal growth as a thread—in this case, via her naturally shed hair—she writes about the judgments of the outside world, such as gender bias, discrimination about her appearance, and being ridiculed for not fitting in.

The creation process is slow and painstaking. She wields each fragile strand of hair like a sharp engraving knife, using clumsy, rigid lines to “carve” these words, stroke by stroke. “As I carefully etched words—representing the harsh words and mainstream societal values I encountered—into the canvas, I focused only on the characters themselves, forgetting their meaning. These painful words were deconstructed, and the trauma they caused turned to ashes, giving new energy to my art.” She explains.

While this canvas-bound public diary is deeply personal, Cao discovers it also speaks for many others who have likewise been hurt by such prejudices. After the work was revealed, she received numerous messages from viewers thanking her. Some said it was not just art, but an awakening of courage and freedom. “Then I realized that there are many ‘Cao Yu’ in this world that I have never met. For me, the real reward is that people see the immense potential within themselves through my work,” she says, “The day this work ends will be the day my life ends.”

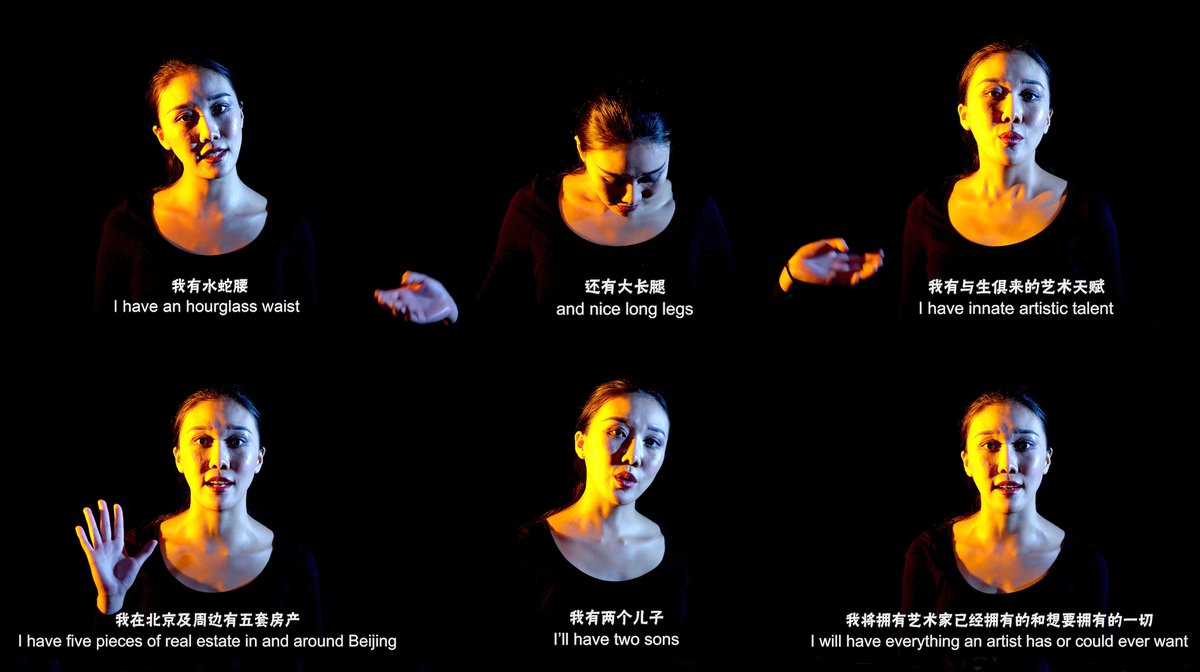

Cao tells TWOC that the inspiration and motivation behind her unconventional subject matter stem from her belief that art has no formula for success. She explored the concept of societal expectations in her piece “I Have” (2017). In this four-and-a-half-minute video, she deliberately highlights the secular achievements people typically pursue by listing her own accomplishments over the past two decades—including her artistic talent, acquired wisdom, blossoming career, and fulfilling family life. Audience reactions vary: Some respond with envy or resentment, while others express admiration or even self-doubt—all while Cao plays the role of a puppet, trapped by society’s rigid definitions of success.

“For an artist, being deemed successful is quite ironic,” she tells TWOC. “I feel the need to constantly discard all the experiences I’ve accumulated, continuously emptying myself to return to a blank slate—only then can I create one good work after another.”

When asked what we can expect from her next project, Cao seems to express an unwillingness to force reality into being. “I never know what my next creation will be. It’s always something that emerges naturally from the things I observe, feel, or experience in life. Art comes from these moments of insight.” She continues, “The element of chance is truly wonderful. The idea of inevitability—it’s just meaningless.”

All images courtesy of Cao Yu

The She-Warrior of Art is a story from our issue, “Youthful Nostalgia.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.