Set against the Tang dynasty power struggle over the succession to Empress Wu Zetian, two assassins meet in a distant town. One must die—and with him, a version of royal history lost to time.

After the death of Princess Taiping, Geshu Liancheng left Chang’an and continued westward to the Anxi Grand Protectorate.

He was once an ice-cold weapon wielded by the empress regent Wu Zetian. He was one of many shadowy figures of the internal security system. They struck fear into the hearts of the lily-livered civil service. Their targets had included, among others, Prince Jing of Yue, the mighty general Xu Jingye, and the poet-bureaucrat Luo Binwang—anyone who dared challenge the sovereign. After the Shenlong Revolution, they were forced to find new masters: Geshu Liancheng threw his lot in with Princess Taiping, while his comrade Yuwen Xin clandestinely offered his services to Li Longji while swearing allegiance to his father, the Prince of Xiang.

Li Longji could not bear the rule of women. The execution of his mother by Wu Zetian still haunted him, and he took as his enemy any woman who aspired to emulate the empress. After the defeat of Princess Taiping, her sons and scores of their henchmen were brutally slain. Only those who stood up to their mother, like Xue Chongjian, were spared.

Geshu Liancheng knew well the saying that “good men are willing to die for their companions,” but this assassin would readily admit that he feared death. Although he could not live up to the righteous, self-sacrificing heroes of the Spring and Autumn era, who might have rushed to give their lives for Princess Taiping, he was unable to switch his allegiance so easily and unwilling to seek refuge with her enemies.

On the night he left Chang’an, Geshu Liancheng carried with him a jade pendant. The pendant was incomplete. He carried only one half. When both sides were joined together, it formed a figure of Jingwei, the mythological bird born from the soul of Nǚwa, who labored day and night to fill the sea with stones.

The other half of the pendant, he knew, had been in the possession of Dugu Meng when she disappeared. The young woman had been a maid to Shangguan Wan’er, but was also known to be skilled in wielding twin blades. She had not been seen since the night of the Tanglong Coup. That night changed the course of the Tang Empire. It had been in the sixth month of the first year of the Tanglong when Li Longji and Princess Taiping launched their revolt. Empress Wei and Princess Anle were killed immediately, but Shangguan Wan’er was spared execution until Li Longji personally intervened. In a rage, he called for her to be put to death, and the legendary female official met her demise under the sword. Ministers came to appeal on her behalf, prepared to persuade Li Longji with tales of her service to the Tang, but it was already too late.

In Anxi, the flames of war seemed distant. Geshu Liancheng lived a life of leisure and seclusion in the mountains. Legend has it that gold was buried beneath the range, but that held no interest for Geshu Liancheng. He was more interested in the way the clouds rolled across the peaks. He found his peace along the Irtysh River and on the shores of Lake Buluntuo. In the mighty landscape of the west, people seemed to shrink. Towering peaks and mighty rivers shielded the place from the outside world. The shepherds leading their snow-white flocks along the riverbanks, the soft cushion of the plains grass, the clouds reflected on the golden ripples of the Irtysh as they rolled from east to west…

Anxi had the most beautiful clouds that Geshu Liancheng had ever seen. The clouds would pile themselves up over Lake Buluntuo and the Tianshan Mountains. Draped over the range, they reminded him sometimes of the flowing sleeves of a singing girl. At other times, the clouds were like the lid of a pot, closed over the landscape. They seemed capable of a never-ending array of colors. He would sometimes lay on the grass, looking up into a sky the shade of blue amber.

It occurred to him that he was looking at a color that had existed long before humans walked on the earth. It was the color of a sky that had looked down as a depression in the soil gathered rainwater for millennia, until it became a lake. Now, the only way to see the lake in its entirety would be to climb the highest peak.

Clouds—fluffy white sheep, shaped by the hands of nature into countless variations—moved slowly from west to east. They embraced the mountains and controlled the rains. They were not fixed to the roof of the sky; the sky was a tree and the clouds emerged from its hollows. With clouds so massive and wondrous, one only had to lie down in the grass or find a precipice to lean against—and then gaze at them, feeling the breeze, experiencing the clouds, taking in the breath and melody of nature...The clouds were a sponge, soaking up all the worries of this earthly life. Their silence was not sanctimonious but solicitous, calling on everyone who walked below to tarry a while and do something useless.

Those were moments to recollect your emotions, to remember how you felt the world around you when you were a child. Up there, that is not a “bird” but a hovering sprite with a sharp grin. Down there, that is not a “chili pepper” but a red witch. “Cloud” is a human word, but they existed long before humans looked up and pondered what to call them. They are one, they are all. They are white, they are colors you could not imagine. They are timeless, but they are always new, undiminished by the passage of birds or of dynasties.

Geshu Liancheng walked to the water’s edge and sat, looking up at the clouds and the silent sky. He could not help but shed tears of joy.

He decided to stay in Anxi.

Three months later, at the beginning of autumn, Yuwen Xin arrived in search of him. Geshu Liancheng felt no fear. It was a moment he had long anticipated. He had heard the bell tolling his time. He had only one request: the duel could not take place in Talu, the village where he had found refuge. That was where Huashuzi lived. She was his adopted daughter. He did not want a girl her age to witness blood spilled.

As the two men made their pact, a girl rushed up to them. She had a pair of coils on each side of her head, just like the images of the child god Nezha. She babbled excitedly that she had discovered a yak that was just as clever as a person. Uncle Chaolu had told her the story…A yak had wandered over to him and given him a lick, and even though the yak’s tongue was prickly, Uncle Chaolu didn’t mind. Five years prior, he had saved the life of a young yak that looked almost exactly like that one. Uncle Chaolu was convinced it was the same yak, coming back to thank him.

Huashuzi believed the story. She was willing to believe in all manner of happy tales. Even if they didn’t happen to her, she would feel just as glad as the protagonist of these stories might. It wasn’t enough for her just to feel glad, though—she always wanted to share her joy. That is why she had raced over to her adopted father to relate the tale. That was how she stumbled upon the tense negotiations between Geshu Liancheng and the assassin Yuwen Xin.

Geshu Liancheng smiled and bent down to pat her on the head. “Your pa’s just catching up with an old friend,” he said. “Why don’t you go and see what Gongsun is up to?”

“You’re being dull, pa,” Huashuzi pouted. “You weren’t even listening to the story!”

“There’ll be plenty of other times for me to hear your stories,” Geshu Liancheng said, “but I’m afraid my old friend has traveled a long way to meet me. He’s come from Chang’an. Chang’an is many months’ walk from here. It is a thousand li away! You can’t imagine how far that is.”

Huashuzi was young, but she was not childish. She made her adopted father vow that he would listen to her story another time, then she raced off to find Gongsun and tell her about the yak.

Geshu Liancheng watched her go, bouncing away like a hare. “Don’t mind her,” he said to Yuwen Xin. “That girl of mine loves making a scene.”

The icicle in Yuwen Xin’s heart began to melt. Geshu Liancheng’s lively adopted daughter reminded him of someone who still haunted his thoughts—someone who had died at the hands of a cruel bureaucrat. In the years when Wu Zetian ruled, informants and corrupt officials held sway, and there were many such miscarriages of justice. His dear friend had been falsely accused. She died in prison. Although Yuwen Xin avenged her, he felt as if he had lost his path in life in the process.

“Tell me, do you think my reputation or my life is more valuable to me?” Geshu Liancheng asked.

“Since you are a fugitive, I don’t believe you place much value on your life. But you have concealed your past from the people here, I assume that you place some value on your reputation.”

“When spring comes, you may reveal to them all that you know.”

“Why must I wait until spring?”

“The snow will come soon. I want to take the sheep down from their summer pastures.”

“I need to take your head back to the capital.”

“Is that what your master has instructed you to do?”

“He doesn’t want the truth of the Tanglong Coup to be known to more people.”

“And what about you?”

Geshu Liancheng turned to show Yuwen Xin his grin. He reached out and absentmindedly stroked one of the grazing lambs. “The snow will come soon. The passes through the mountains will be sealed. Even if you kill me now, you will have no way to return to Chang’an.”

That night, they gathered around the brazier. Sparks floated out of the coals and into the deep-blue night sky. Madam Gongsun, hearing that a visitor had come from afar, had ordered a lamb slaughtered. The meat furnished the table, alongside warm milk, melons, and grapes. Yuwen Xin put his sword aside. Madam Gongsun urged a cup of warm milk on her guest.

Huashuzi was happy to be the center of attention at the impromptu gathering. Everyone paid attention to the story of the grateful yak. Her smile warmed them as much as the stove. Softened by the scene, as well as by three rounds of wine and a bellyful of lamb, Yuwen Xin began to feel something he had not felt in a long time.

Geshu Liancheng did not trouble his assassin, but helped him to settle into a small wooden cabin. He made sure he had a change of clothes. When Geshu Liancheng himself bedded down for the night, he kept his hand on the hilt of his sword. Nobody inspecting him at rest would be quite sure whether he was fast asleep or merely resting his eyes.

Cold memories caused Geshu Liancheng to stir at midnight, and he went to the brazier with his blanket wrapped around his shoulders. He crouched and added charcoal. The glowing coals were an island of brightness in the darkness around him. He was reminded of the river lanterns that he had set over the Wei River. One of the lanterns had been for his sister. He remembered a dot of light gliding across the Guanzhong Plain, then going out in the boundless flowing darkness.

That same night, Yuwen Xin also found himself floating through the desolate expanse of his memory, tormented by blasts of heat and icy winds. Sometimes, his forehead burned, while he felt cold everywhere else. He looked up finally when he thought he saw a figure approaching. At first, the face was unrecognizable, but as it drew nearer, and the flames in the brazier glowed brighter, he thought he knew who it was—a memory that was always close at hand, but forever remote...Yuwen Xin reached out his right hand and smoke streamed between his fingers. He pulled his blanket tighter. He felt for the first time that he was in a wilderness even more vast than a thousand Chang’ans. He was surrounded by a darkness deeper than any he had ever known. He wanted something that he could hold onto, and that face lit by the flames seemed to answer his desires. He realized that his eyes were wet with tears.

Following the night, dawn was like stepping into a second dream. Yuwen Xin realized that his task—the assassination of Geshu Liancheng—was no longer as urgent as bare survival. The only thing that mattered in that remote frontier town in the mountains of Anxi was to remain alive.

The winter was long. Nobody else arrived from Chang’an. The mountains were blanketed with snow. Elk descended into the valleys, hoping that the withered grass of the lowlands would be enough to get them through the season. Some of the elk were shot by hunters, and some were captured and penned near the village.

Huashuzi cared for a young lamb at her bedside, keeping it in a paper box beside her warm kang. When the lamb stuck its head out to take in the world, everyone admired its beautiful eyes, long eyelashes, and soft pink mouth. She took her pet out on clear days, tramping down the trails cleared by the shepherds as they walked their herds up to the snow-covered pastures to graze. The herders lost many sheep in the fierce snowstorms. The blizzards swept in with such ferocity that it seemed like they would fill the entire sky. After the snowstorms, there was only silence. The endless expanse of snow ran to the horizon, where it seemed to become one with the sky.

After the storms passed, Talu added up their losses: one hundred and fifty ewes dead, along with ninety lambs, eight cows, and nineteen calves. When the sun came out again, it shone down on the carcasses scattered across the drifts. A harsh wind whipped the hides and bones.

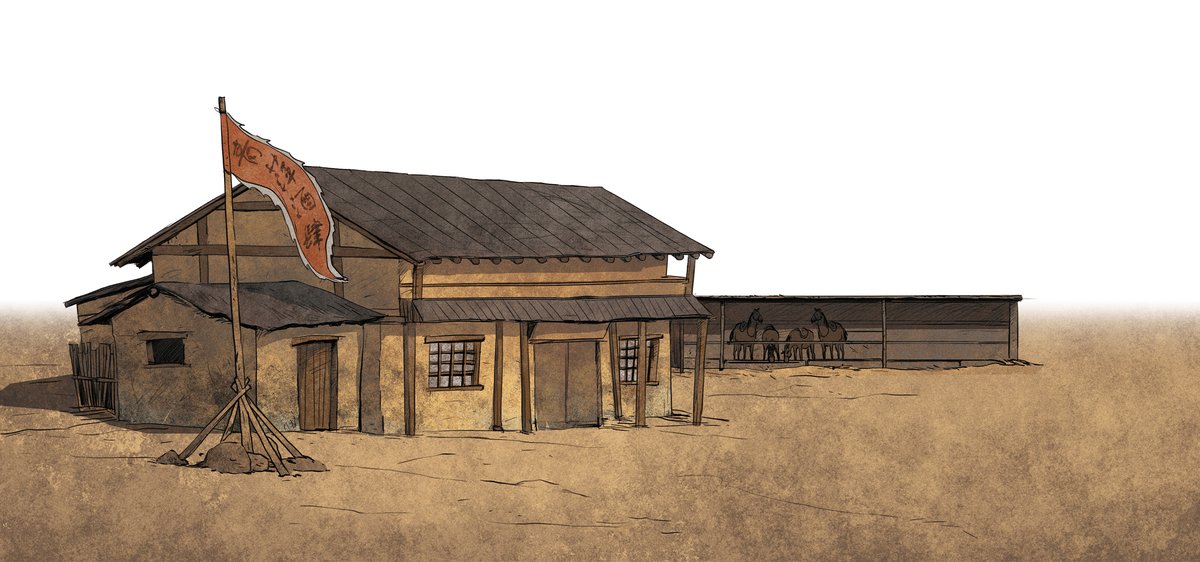

When spring came the earth seemed to have come together again. Everything was moist and fertile. The pastures sprouted tall, green grass. Along with the change in the season came more guests from afar. They went first to Madam Gongsun’s tavern. The Qingping Inn, as it was known, was beside a major route through the area, and it attracted many of the vagabonds and merchants that passed through. Stopping by, one could look up at the clouds breaking on the towering peaks and forget about the petty concerns of this mortal world.

When Gongsun saw the men enter, she clutched her purple robe tighter around her shoulders and called for the waiter to see to them. They were a small group, each looking fierce, and wearing mutton chops. Their leader was a thin man with a sword in his fist and a dagger in his belt. His was not the build of a wasted itinerant, but the wiry frame of a martial arts master. Behind him came a stockier man with rippling muscles and powerful haunches. Their cruel intentions were obvious. The atmosphere became somber. The thin man spoke to his lieutenants in a Chang’an accent, and one of the men produced a sheet of paper with a man’s portrait painted on it. There was no mistaking the face—it was Geshu Liancheng. Fear flickered on the waiter’s face and the leader of the gang narrowed his eyes. “You know this man?” he asked.

“Never seen him,” the waiter said in a trembling voice.

“If you’re lying to me,” the leader of the gang said, leaning forward menacingly, “my blade will give you no mercy.”

Madam Gongsun pushed the waiter aside and confronted the men. “Who are you?” she demanded.

The thin man’s face was as cold and impassive as a block of ice. “We are attempting to locate a fugitive,” he said, finally. “He is the man in the picture.”

“You won’t find him in here,” Madam Gongsun said.

The thin man made a motion and his gang jumped into action, leading a trembling, pathetic-looking man into the tavern. “What this man says contradicts what you have just told us.” He gestured at his short, fat informant, who had clearly wet his pants out of fear. “He tells us that the man we seek is in this very tavern.”

“My tavern is a humble place,” Madam Gongsun said. “It will not take you long to search it. But I warn you, if your search turns up nothing and you cause trouble for my guests, you’ll face my blade.” Her tone was steady. Her face betrayed no trepidation.

Without a word to the innkeeper, the thin man motioned for his men to begin their search.

As the search commenced, the patrons glanced at each other anxiously and began moving toward the door. They found it blocked. “You may leave after our inspection,” the thin man said. “We don’t want to let the fugitive slip by us in disguise.”

The atmosphere grew tense. Looks were exchanged by the patrons. A red-faced drunk exploded with rage at the gang blocking the door. He was a local man, known for being a bit fractious. The thin leader of the group listened for a moment. Suddenly, there was a glint of flame on steel and the drunk man’s head clattered to the floor. Before they could step back, blood spattered the clothes of the onlookers.

“Murder without provocation,” Madam Gongsun said. “The law of the land still applies in this remote place.”

“Law of the land?” the thin man asked. He flicked droplets of blood from his hands. “We are the law of the land.” He fished from inside his cloak a token marked with the name of the imperial Thousand Oxen Guard.

Madam Gongsun clenched her jaw and remained silent. Within a few moments, the search was complete. The fugitive was not there. The silent man strutted a circle around Gongsun. He studied the faces of each of the patrons. Some of them trembled in fear and wet their pants, while a few clenched their fists in mute defiance. The leader’s inspection was over quickly, but it seemed to stretch on for hours. The thin man pushed aside the door of the tavern and barked as he strode away, “If any of you are bold enough to harbor a fugitive, know that the punishment is death!“

When he was gone, whispers filled the tavern. “Are they really from the Thousand Oxen Guards?” someone muttered. “Maybe they’re just trying to scare us.”

That night, there was a murder in Talu.

The victim was the thin man who had charged into the tavern that morning. The eagle totem of the Tiele people was found scrawled on the wall of a nearby guesthouse. A local drunk passing by claimed to have heard a child’s voice singing a chant that was identified by a knowledgeable local man as a Xianbei-language tune called “The Song of the Chi Le”:

The Chi Le plains spread out under

The towering Yin Mountains.

The sky hangs like the felt flap of a tent,

Covering the land from up on high.

The sky is boundless;

The land has no end.

Winds blow gently across the grasslands,

Unveiling the grazing cattle.

Some said the murder might have been the work of bandits. The village was firmly in the borderlands, and it had never been a particularly peaceful place. Yuwen Xin did not share this opinion, but his suspicion fell on Madam Gongsun. He had sized her up and knew that her levels of spiritual and martial cultivation made her at least the equal of Geshu Liancheng.

During his time in Talu, Yuwen Xin had investigated the woman and her past. Locals told him that she went also by the name Hongfu. She chose that nickname because she admired a Sui dynasty martial arts heroine who went by that name. Madam Gongsun claimed to be from a prestigious clan from the west of the Yellow River. In her youth, she fancied herself another Hua Mulan, learning martial arts from her father, and learning to shoot from horseback. At the time, there were Tang garrisons in the region, but they were overshadowed by the private militaries of the local clans. They were given a degree of sovereignty in exchange for swearing allegiance to the Empire. Since they fought for their homelands and their families, they were much fiercer in battle than the soldiers of the Tang, whether they came from the Central Plains or the Uyghur Khaganate.

Gongsun, in her youth, had been more militant than her elders. She once forced a brigade of women fighters to push back Tubo marauders. Once, she had ridden alone into the wilderness, returning only after several weeks. She was forced to flee her homeland after turning down a marriage arranged with the son of a powerful clan from Liangzhou. She found refuge in Anxi. There were many others like her there—vagabonds, hermits, citizens without a state, and nomads seeking shelter. It was a temporary place for temporary people. The world is a vast place; they treasured every reunion.

“When did she show up in Talu?” Yuwen Xin had asked Geshu Liancheng.

“Three years ago.”

“Three years?” Yuwen Xin considered this. “It was right after the Tanglong Coup, then.”

“I suppose.”

An audacious leap of reasoning presented itself to him.

That year, when the spring rains melted the snow, Yuwen Xin mentioned the Jingwei pendant again.

“You know its history—a history that you’ve chosen to conceal. Why do you want to hide it? I think it’s because it stands for things that you aren’t ready to face yet. You can’t wipe those things away. They are always going to be there, pricking at you. You still have a sense of morality, so I know that you must feel guilty, but you aren’t willing to face those things. You’re a weak man, after all. You think you can walk away from the past. You try to convince yourself that you really are the righteous man that you pass yourself off as now. To the people in Talu, perhaps you are a hero. But you yourself know the truth: the past is still waiting out there for you. The past keeps reminding you of your own dark side.”

A year or so before, Yuwen Xin explained in a pleasant, meditative way, that a man named Dugu Rendong had sought him out. Dugu Rendong wanted to do a favor for his sister. He gave Yuwen Xin the pendant. It had once belonged to his sister, Dugu Meng.

“Where is she?”

“She died in Chang’an, according to Dugu Rendong.”

“Did she return to Chang’an?”

“Her plan was to assassinate Li Longji.”

“To avenge Shangguan Wan’er?”

“She never forgot that night.”

Dugu Meng’s father was killed in battle. Her mother was unhappily remarried. Her life as a girl had not been easy, but it changed when Shangguan Wan’er took notice of her talent, took her under her wing, carefully instructed her, and took her as something like an adopted daughter. In the end, Dugu Meng was willing to die for her companion. The thought made Geshu Liancheng lower his head. He gazed east, lost in thought. He had to admit to Dugu Rendong that he lacked his sister’s bravery.

“You used her,” Yuwen Xin said. “You wanted to gather information about Shangguan Wan’er, so you took advantage of her trust. Right up until the moment the coup was launched, she believed that you would protect Shangguan Wan’er. But you lied to her, the same way as you lie to the people here. You’ve built an image of yourself as a shining hero, hoping to conceal your pathetic past. What are you afraid of?”

On the way back, Yuwen Xin noticed Huashuzi studying him.

“You had a fight with my pa, didn’t you?” she asked. “You should make up with him. He’s a good man.” Her innocent gaze forced him to turn away. Huashuzi was confused about why the man would not speak.

“Don’t worry,” Yuwen Xin said, finally, bending down to stroke her hair. “We’re good friends, your pa and I.”

“Pinky swear?” Huashuzi begged. She recited the requisite rhyme: “Pinky swear! If I hang, I don’t care! A promise lasts a thousand years!”

“Fine. Pinky swear.”

She recited the rhyme again.

Yuwen Xin began walking away from her, but then glanced back. Huashuzi was still studying him. Her smile was so innocent. He could not help but remember the person from his past. There was a gust of wind, and sand stung his eyes. He wiped his face clean with his hands.

Snow began to fall shortly before midnight. It would be the final snow of the season, signaling the end of winter and the return of the warm, wet season. The sound of clattering swords at the oasis echoed through the snow. The stars shone down on the distant bloodshed. There were bloodthirsty roars, followed by a blue-black bolt of light as the Green Serpent Blade slashed. The sword moved as delicately as the serpentine whorls picked out in the metal of its blade. Geshu Liancheng wielded it with ease, dancing between offense and defense, holding off his challengers with only Gongsun at his side.

Yuwen Xin saw that the strength of the two was gradually fading. He knew that if he joined the fight, he could have easily struck down Geshu Liancheng, but he chose not to, watching from his hiding place behind a boulder. He certainly could not have predicted the arrival of the mounted, masked fighter who intervened on the side of Geshu Lianchang and Gongsun. The new arrival swung a blade in each hand, and in an instant, two skulls were split from their bodies. The heads rolled across the wasteland, awaiting the arrival of the wild dogs that would carry them off. The three fighters together were more than a match for their challengers, who quickly went into full retreat. The battle concluded, and the mysterious fighter mounted and rode off.

Yuwen Xin gave chase. Two horses raced across the mighty desert like a pair of ants.

Yuwen Xin smiled bitterly when he unmasked the mysterious fighter. Life is far stranger than any dream, he thought to himself.

The moonlight was soft. He found a place at a nearby relay station and slept until the crimson light of dawn began to creep through the shutters. He went out to his horse, studying the silent mountains that shimmered in the glow of the morning. Still wrapped in the mists of the previous night, they were a riddle that he knew no mortal would ever solve.

That was when he made his decision: he would, as he had intended, and as they had agreed, challenge Geshu Liancheng to a duel. But he had given up on any schemes to murder him. If Yuwen Xin beat Geshu Liancheng fairly, he would cut him down without compunction. If Yuwen Xin lost, he would accept that his mission was a failure.

Yuwen Xin had worried that Geshu Liancheng might intentionally leave himself vulnerable to an attack, but that now seemed impossible. A swordsman might be dishonest in other affairs, but he was always true to his blade. To let down the sword he carried in his hand would be to profane the faith that allowed mastery of his craft.

The death of the swordsman did not occur in duel, but after it. The contrast of fresh blood against the blue sky was beautiful. Black birds flew from the forest. The clouds flowed. The wind covered the sounds of death. They were very faint.

Talu glowed orange under the setting sun. A drunkard perched on a roof looked over his cup. A penitent recited prayers for the dead in the temple. A monk brushed past a vagabond. A poet walked a familiar path, gazing to the east.

In Chang’an, Yuwen Xin had heard that Geshu Liancheng was a member of Princess Taiping’s rebels, but before joining her, he had been an assassin for Wu Zetian and then Empress Wei. He had been responsible for the deaths of many loyal subjects. That was why he deserved to die. There were other versions of the story, though. Some reported to Yuwen Xin that Geshu Liancheng, despite serving Wu Zetian, had a change of heart. He had never truly thrown his lot in with the Prince of Xiang and Li Longji, nor had he been fully supportive of Princess Taiping. He could still decide his own path in life, and he may have even offered aid to Shangguan Wan’er. One reason for that may have been that Wan’er had shown kindness to his wife. Another was that even though Wan’er did the bidding of Empress Wu, she remained loyal to the rightful heir of the Tang—the Li family.

Li Longji exterminated Empress Wei’s camp during the Tanglong Coup, but killed Shangguan Wan’er only out of personal enmity. Not long after, Princess Taiping’s struggle against Li Longji came to an end. Her fate was the extermination of her entire family line and the confiscation of their property. The victors rewrote history as they saw fit. Historians were instructed to depict Wan’er and Princess Taiping as power-mad enemies of the nation, warnings against the influence of women in politics. This matched Li Longji’s personal beliefs. With his rise to power came the end of women’s progress in politics. Anyone with ties to Wan’er and Princess Taiping was eliminated, since they might challenge Li Longji’s version of history.

And so, Li Longji swept aside his enemies, and those that might have stood in the way of his ascent to the throne. It is recorded in history that he rectified the path of the Empire. Until the arrival of An Lushan, he ruled over a golden age. Shangguan Wan’er and Princess Taiping became footnotes in the records of the emperor’s great deeds. Their deaths were recorded in a few terse words, but those who lived through that time remembered much more. They experienced events that defied judgments of right or wrong. As for who was justified, who was dishonest, whose blood deserved to be spilled, and whose name should be praised—Geshu Liancheng and his friends had no answer. The problem was that they had seen too much. If they had not flown the capital, they would have become ritual sacrifices.

A year later, when the snow melted, Yuwen Xin returned to Anxi.

Carved into the wooden token of the Thousand Oxen Guard at his waist was this name: Geshu Liancheng.

He went to look for Gongsun at the Qingping Inn.

“You’ve been promoted,” Gongsun said, seeing him.

“It is thanks to all of you.”

“Two days from now will be the anniversary of his death.” Madam Gongsun fixed her gaze on his familiar face. “Most people will never guess that Geshu Liancheng was not one person, but two.”

“Men who make their living by the blade live for the present. The future is not promised to us.” The wine was served, and he threw down a cup in one go. He recalled that day in Anxi and the terrible duel...Yuwen Xin had slain Geshu Liancheng—but which Geshu Liancheng? In the days when Wu Zetian was consolidating power against the Li clan, the two men had made a pact to stay on opposing sides. That way, whichever faction prevailed, one of them would survive. But that was the fate they accepted: there was no way that both of them would make it out alive.

“How is Huashuzi?”

“I told her that her pa went out west and would eventually return. She seemed to sense something was wrong. For a while, she was very sad. Would you like to see her?”

“Seeing her only to leave her again would only add to my sorrow. It’s better for her to stay and live with you.”

“She’s a kind-hearted girl. She doesn’t need to suffer the same fate as our generation.”

“Kind hearts—” Yuwen Xin began, then broke off.

They went to pay their respects at Geshu Liancheng’s grave. A cherry tree in front of his tomb was blossoming. A breeze knocked a petal down and sent it spinning into the distance. Gongsun asked Yuwen Xin about his plans. He offered only that he was headed to the capital to carry out a task. They stayed until dusk, then bade each other farewell. Yuwen Xin walked toward the mountains, shrinking against their mammoth edifice.

Huashuzi arrived at Gongsun’s tavern a short time later. Gongsun gave the girl a task: she was to deliver half of a jade pendant to Lady Mingyue. One of the few poets in Taru, Mingyue was a woman in her fifties but she still retained a youthful beauty. Huashuzi raced toward her home, trying to arrive before the dark clouds began to dump rain on the village. She did not expect Mingyue to start weeping when she pressed the pendant into her hand. Her tears fell on the soil of Anxi, and on the tiny characters engraved on the pendant:

May your memory resound across generations

Like the aroma of the pepper blossoms.

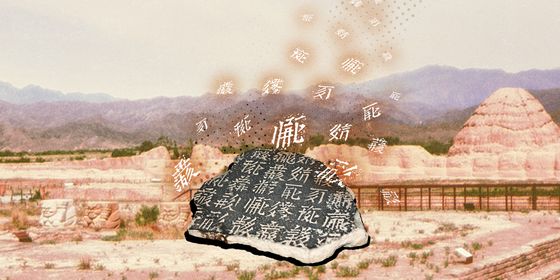

Author’s Note: Despite her fame as a prominent stateswoman and talented poet of the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), Shangguan Wan’er’s tomb remained undiscovered until 2013, when it was found in Xiangyang, Shaanxi province. The discovery revealed her previously unknown friendship with Princess Taiping, another influential political figure of the time and the daughter of Empress Wu Zetian. Shangguan’s epitaph, which inspired this story, recounts how Princess Taiping mourned her death and wrote poems in praise of her life. The last two lines of my story are borrowed from one of those poems.

I’ve always admired Lu Xun’s Stories Old and New for its innovative retelling of myths and historical tales. Having been drawn to wuxia novels from a young age, I began to imagine a story about commitment and hermits. The protagonists, all people scarred and exiled by power—those once manipulated who now seek escape—are at the heart of this narrative. My goal is to capture the fleeting moments of brilliance in their lives.

Illustrations by Xi Dahe

The Jade Pendant | Fiction is a story from our issue, “Youthful Nostalgia.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.