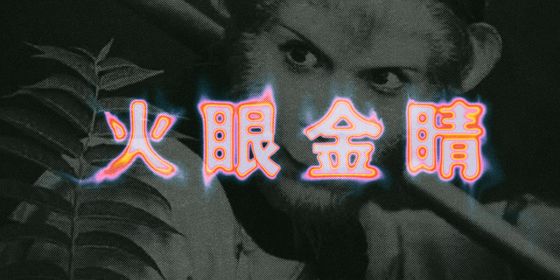

Learn these essential Chinese “chengyu” to praise a free spirit, or to discipline a rebellious child

Amid the frenzy of the Chinese New Year box office, Ne Zha 2, an animated film by director Yang Yu, better known as Jiaozi, has skyrocketed to the top of the chart. Already the world’s highest-grossing animated movie in history, the film’s success is partly driven by its reimagining of an ancient myth and the traditional values it once conveyed.

Loosely based on stories from classic Chinese literature such as The Classic of Mountains and Seas (《山海经》) and Investiture of the Gods (《封神演义》), the franchise follows Nezha, a rebellious and prickly boy with a dangerous power destined to bring calamity to the world, as he struggles against fate and societal expectations. With the help of his friends, family, and mentors, he seeks to redefine his destiny and fight against true evil forces threatening the world.

Ne Zha’s story continues to resonate with today’s youth in China as they, too, want to break free from traditional norms and carve out their own identities in a rapidly changing world. Ne Zha’s signature line, “My fate is in my own hands (我命由我不由天),” makes the character’s journey a powerful symbol of personal freedom and resilience.

TWOC has gathered a list of chengyu describing a free spirit that you can use to join the discussion of this legendary character. But be cautious, as many of these idioms carry a negative connotation—being a rebel wasn’t always celebrated in traditional Chinese culture.

Learn more about Chinese idiom:

- Idiomized: Join the Wukong Hype in 4 Characters

- Idiomized: How to Complain About Your Boss in 4 Characters

- Idiomized: How to Condemn a Hypocrite in 4 Characters

Wild and untamed 桀骜不驯

If a person has a violent temperament, is resistant to discipline, or is unwilling to easily submit to authority, you can say that person is 桀骜不驯 (jié’ào búxùn).

He has an unruly personality, often going against his teacher’s guidance and doing things out of line.

他的个性桀骜不驯,经常违背老师的教导,做一些出格的事情。

The phrase 桀骜 (jié’ào, unruly) originated in The Book of Han (《汉书》), the official history of the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE – 25 CE). It was used to describe the rebellious leader of the Xiongnu, a group of nomadic tribes in the north, and his refusal to submit to the Han court at the time: “He is so unruly, there is no way that he’ll willingly offer his beloved sons as hostages. (其桀骜尚如斯,安肯以爱子而为质乎?)”

The renowned general Xiang Yu (项羽) is an apt representative of this idiom. Recorded in detail in the Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》), a history of ancient China by the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) scholar Sima Qian (司马迁), Xiang’s violent and rebellious character ultimately led to his downfall after he suffered a major defeat in the Battle of Gaixia.

Lu Xun (鲁迅), one of the most acclaimed vernacular writers of the Republican era, also used the phrase 桀骜 in his 1926 essay “In Memory of Liu Hezhen (《记念刘和珍君》),” mourning the young female student who was killed during a protest against foreign aggression in Beijing: “I had always imagined that any student who could stand up to the authorities and oppose a powerful president and her accomplices must be rather bold and intractable (桀骜锋利), but she nearly always had a smile on her face, and her manner was very gentle.”

Unbridled and unscrupulous 肆无忌惮

This idiom was initially linked to a person’s character and moral traits. The Doctrine of the Mean (《中庸》), a central creed of Confucianism written in the second century BCE, has this summative description of what it is like to be “unbridled (无忌惮 wú jìdàn)”: “A petty person acts contrary to the doctrine of the mean, being unprincipled and without any restraint (小人之反中庸也,小人而无忌惮也).”

But over time, 肆无忌惮 (sìwú jìdàn) came to describe actions and behavior carried out without any scruples or reservations. In “A Letter to Wang Guiling (《与王龟龄》),” scholar Zhu Xi (朱熹), who lived during the 12th and 13th centuries, wrote : “The trend of abandoning parents and disregarding the words of the ruler is currently on the rise, without any restraint (遗君后亲之论交作,肆行无所忌惮).” This neutral tone, however, was largely abandoned in later usage, and at modern references, the word “肆 (sì)” was added to imply a negative connotation.

The kitten always likes to wreak havoc at night without restraint, breaking several cups.

小猫总喜欢在夜里肆无忌惮地捣乱,打碎了好几个杯子。

Cynical take on life 玩世不恭

First appeared in the Book of Han (《汉书》), the phrase was used to comment on the life of Dongfang Shuo (东方朔), an outstanding literary figure and master of poetic composition: “He navigated the court with a recluse’s detachment, mocked the world with a jester’s wit, yet his unconventional ways clashed with the times, leaving his talents unrecognized (依隐玩世,诡时不逢).”

Directly translated as “playing the world and paying no respect,” 玩世不恭 (wánshì bùgōng) describes a carefree attitude toward life that arises from dissatisfaction with reality. It can be seen as a philosophy of detached self-liberation, where one adapts to the ways of the world without being overly concerned with trivial details, particularly for those who have faced setbacks.

He prides himself on having seen through the vanity of the world, and there’s always a touch of nonchalant defiance in his words and actions.

他自诩看破红尘,言行间总透着一股玩世不恭的劲儿。

Lawless and reckless 无法无天

The chengyu originally refers to the specific act of disregarding national laws and moral principles. In Chapter 33 of the Qing dynasty novel Dream of the Red Chamber (《红楼梦》), the protagonist Jia Baoyu (贾宝玉) is interrogated by his father Jia Zheng (贾政) for getting involved with the royal family’s favorite opera actor. “It’s one thing if you don’t study at home, but how could you go and do something so lawless? (你在家不读书也罢了,怎么又做出这些无法无天的事来?) ” chides Jia Zheng, furious about his son’s unfilial and reckless behavior.

Now, it is used to describe any disorderly behavior without restraint.

After Dad and Mom went on a business trip, my little brother became like a wild horse without reins, causing chaos at home and acting with utter disregard for rules.

爸爸、妈妈出差后,小弟就像一匹脱缰的野马,在家里简直是无法无天了。