Evading strict censorship around religious and supernatural content, Chinese horror games have long used cultural elements like paper money, ancestral tablets, and red lanterns to evoke horror and tension—yet now, audiences are seeking deeper thrills

On a quiet night in a remote mountain town, Zhang Yutong is sent to investigate a burning coffin—a suspected arson. When her car suddenly breaks down on the way, the detective and her colleague are left stranded in an eerie, unfamiliar village. Beside the car is a derelict wall with “Talk science, break superstition” scrawled across it. Walking down the street, she passes a local grocery store, a clinic, and a bulletin board displaying an obituary, before turning to a red-brick building from which blood slowly seeps. Stepping closer, she is bathed in a crimson light, and time begins to twist into a nightmarish loop. Coffins, wreaths, and paper dolls loom ominously all around her, and a blood-soaked notebook, filled only with the word “debt,” revealed when she takes a candle to illuminate the darkness, seems to haunt her at every turn.

Wracked with panic, the 25-year-old stumbles away, desperate to flee, but her path is blocked by a phantom hearse. The vehicle’s back door creaks open, and Zhang finds herself walking toward it, unable to fight the urge to see who, or what, lies inside. Waking with a fit, she discovers she’s been admitted to the town hospital.

This haunting scene sets the tone for Firework, a Chinese horror game released in 2020 in which Lin Lixun, played by Zhang above, is tasked with solving the case of a widow’s desperate attempts to protect her daughter from her deceased husband’s parents. The torment begins when they cast a spell intended to rid the wife of her soul, aiming to turn her body to a vessel for their dead son. The game draws players into a world of sorrow, grief, and fear, offering a deeply unsettling yet goreless experience of Chinese horror based on local mythology and folklore. “It resonates so deeply,” says Zhang, a secretary in the medical industry living in Zhejiang province. “Chinese audiences might not be afraid of American or Japanese-style horror, but we’re truly terrified of the Chinese-style ones. This kind of fear is deeply ingrained in our DNA. We understand it on a very profound level—probably much more than people from other countries.”

Since Firework’s release, China’s gaming market has been flooded with horror titles, but few have come close to usurping the seminal title’s thrills. Then, at the end of last year, Incantation—a first-person horror mystery game set in a cult village and adapted from the 2022 horror film of the same name—reignited debate about the state of the genre. Critics argued that, despite receiving mostly positive reviews, the game relies on the same old tropes—missing family, apparitions, and cult rituals—adding to the genre’s oversaturation and signaling that the Chinese players are ready for a different kind of scare beyond traditional horror elements.

Read more about gaming in China:

- The Year in Play: China’s Top Video Games of 2024

- China’s Winding Path to Gaming Literacy

- Pixel Passion: Stories of Hope and Hustle From China’s Indie Game Makers

Like their counterparts in film and literature, who must also navigate official censorship of overtly horrific elements, Chinese horror game creators often draw inspiration from a shrinking pool of permissible subject matter. According to a 2021 report by state media Xinhua Net, regulatory authorities held discussions with major gaming platforms, including Tencent and NetEase, emphasizing the ban on illegal and harmful content such as pornography, violence, and horror. Somewhat paradoxically, psychosis or the ingestion of psychedelic drugs—strictly controlled in China—has been used in some games to explain the presence of ghosts. However, most developers play it safe, relying on themes like ancient civilizations, Chinese folklore, and mysterious incidents, often requiring players to uncover clues, solve puzzles, and explore chilling storylines to reveal a hidden truth.

While Chinese horror films have historically struggled to rouse domestic audiences, horror games like Paper Doll (2019) and Firework have achieved breakout success for their portrayal of traditional Chinese cultural elements and exploration of real-world issues. In a 6,000-word review of Paper Doll, Yoshitaka Maki, producer of Resident Evil – Code: Veronica (2000), lauded the game’s originality after its release, saying, “The Chinese horror elements bring a truly fresh experience.” Seeing a unique gap in the market, developers and publishers continue to explore this fertile ground, with some of the more creative teams aspiring to shake up the industry in the process.

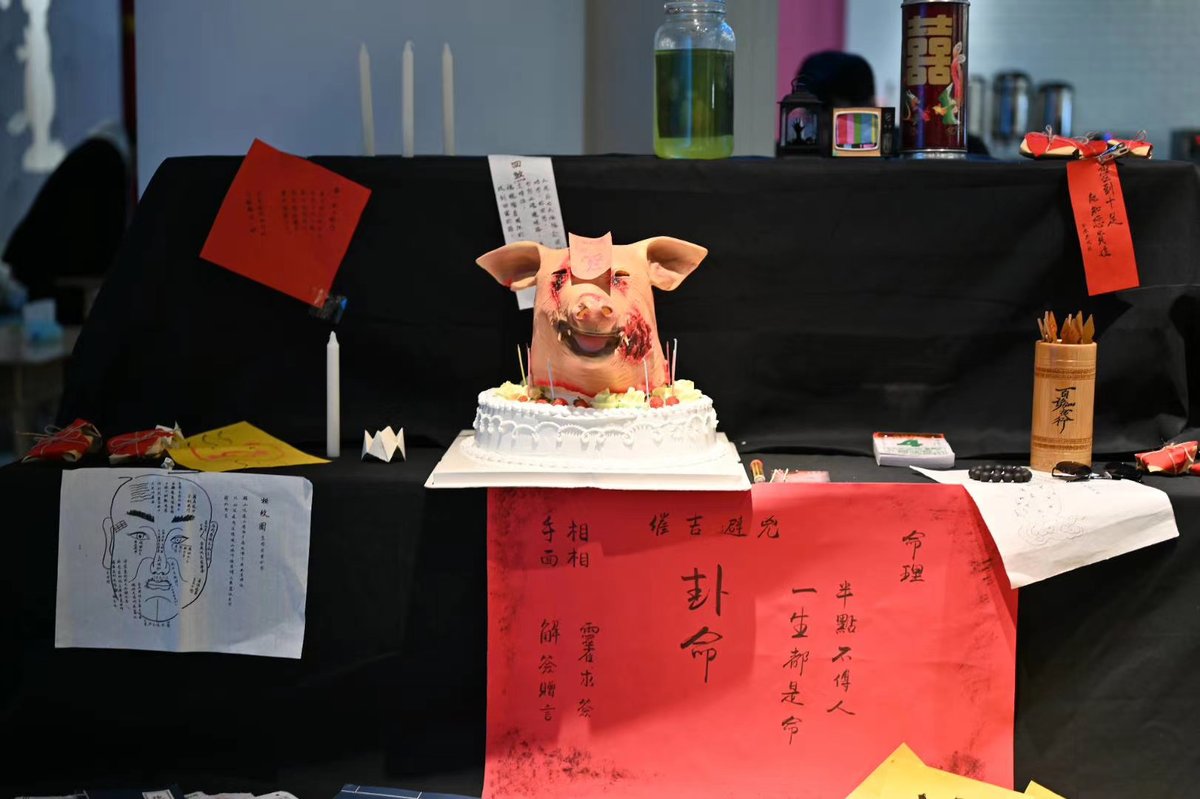

Chinese horror games typically take the form of walking simulators, a subgenre of adventure games that emphasize environmental interaction and puzzle-solving while steering away from jump scares or gore, setting them apart from their American and Japanese counterparts. By weaving traditional cultural symbols—such as paper money, ancestral tablets, paper effigies, red lanterns, and embroidered shoes—into storylines, they offer a fresh take on horror rooted in the superstitions, rites, and practices of Chinese feudal society.

This narrative-driven approach has become a hallmark of Chinese horror games, swapping cheap scares for immersive narratives that explore ongoing societal problems. Although typically short, with playtimes averaging around five hours, these games leave an impression by confronting stories close to home: Paper Doll takes aim at human greed, the Paper Bride series (2021 – 2023) explores themes of outdated superstitions and the abandonment of baby girls, Black Sheep (2022) revolves around school bullying, and Firework addresses human trafficking.

“The fear isn’t just about ghosts or monsters,” Zhang tells TWOC. “It’s about tapping into real-world horrors, like human trafficking or the oppressive traditions of feudal society. It’s the connection to our own history and culture that truly scares us.”

The history of video games in China is relatively short, with the first titles entering the market in the late 1980s. The first Chinese horror game, Ghost Temple, wasn’t released until 2001. Inspired by the 17th-century horror anthology Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio (《聊斋志异》), the PC-based role-playing game received both domestic and international praise for its haunting visuals and atmospheric score. Often dubbed China’s version of Resident Evil, Ghost Temple tasks players with rescuing the ghost of a young girl from the haunted Lanruo Temple alluded to in the title. However, the game’s initial spark faded when players became increasingly frustrated with a litany of glitches, leading to lackluster earnings. It wasn’t until the late 2010s and early 2020s when Paper Dolls and Paranormal HK (2020) made headlines that Chinese horror games began to regain attention.

This resurgence of interest is evident in the genre’s many fans online. Over 170,000 posts related to Chinese horror game recommendations can be found on the social media platform Xiaohongshu, with one viral comment casually declaring, “Of course, Chinese people know best how to scare other Chinese people.”

Yet, some of this initial excitement has since turned into disillusionment and boredom with the genre. In the first half of 2023, fans were treated to at least 10 Chinese horror games. But Huang Zhen, a 26-year-old game influencer from Guangdong province, bemoans that many of them center around similar elements—superstition, human trafficking, and the suffering of women—something she says leads to “aesthetic fatigue.” “Chinese horror is subtle and slow, but when it becomes formulaic, it loses its edge,” Huang says. She cites last year’s Laughing to Die, a role-playing game that follows a grandmother trafficked to a village for marriage, unable to escape her fate. “It feels cruel to just be a passive observer. Watching helplessly made me more angry than sad…I’d like to see something different in these games.”

A major issue many fans of the genre mention is the feeling that modern horror games overly rely on puzzles and linear narratives, where the player is more of a passive observer than an active participant. An article by gaming media outlet Youyu Dashijian concluded in 2021 that puzzle-based games are popular because they help avoid official censorship and lower development costs. Na Qi, lead developer of Ghost Feed, released in 2023, agrees. “Text-based puzzle games are more manageable in terms of cost and return,” the 39-year-old from Sichuan province tells TWOC. “If you enter into the action genre, as Paper Doll did, players will expect high standards. But with text-based games, players tend to have more forgiving expectations.”

Na acknowledges that the entry barrier for horror games is low. After learning coding, design, and illustration from scratch, Na’s team spent about 300,000 yuan and one year developing the text-based game Ghost Feed in honor of his cousin, who passed away in early 2021. Inspired by a surreal funeral experience Na had where Daoist priests instructed attendees to perform various tasks, such as lighting incense, to guide the deceased to the underworld, the game eschews jump scares for a more interactive approach, inviting players to communicate with spirits via different Daoist rituals.

Aware that the growing number of Chinese horror games makes it increasingly difficult to create something truly unique, Na and his team chose to focus on storytelling. For him, effective horror isn’t just about conjuring images of death. “There are many ways to evoke anxiety and intensity,” he says. In Ghost Feed, when the protagonist first travels to the underworld, they’re met with a quiz that feels right out of school—except it involves measuring a coffin, and wrong answers invite death. “The test evokes a sense of fear or, for some, brings back memories of anxiety and being under pressure. Our goal is to create a compelling narrative, not just scare players,” Na adds. He highlights moments like a surreal cyber funeral in the game, where rockets, spaceships, and luxury cars are among the offerings to the dead, adding an emotional and visual depth more likely to resonate with younger players.

Na’s outlook on play over panic aligns with that of other industry specialists. In a 2021 interview with gaming media outlet Longhuboom, Firework producer, known by the online handle Moonlight Cockroach, shared the challenges of balancing a sense of horror with gratifying gameplay. “When we released the demo for Firework, some players felt it wasn’t scary enough, while others were too frightened to continue,” he said. “If you make it too terrifying, with a ghost’s face appearing every two steps, players will quickly lose interest,” he added, alluding specifically to the frustration he felt while playing a foreign horror game that relied on repeated jump scares. “They might even demand a refund, and leave a negative review.”

Faced with tightened regulations for acquiring release licenses and bans on depicting supernatural themes, developers face a difficult decision: forgo a mobile release license and bypass restrictions by launching on distribution platforms like Steam, or risk censorship while reaching a larger audience—and potentially significant earnings—via mobile platforms. However, according to a report by media outlet 36Kr, even the few games that made it onto mobile platforms have limited ways to make money, relying solely on one-time payments and in-game advertisements, with few options for repeated in-game purchases like virtual currency or assets.

Xu Duoduo, a publishing director at Shanghai-based game publisher Gamera Games, admits that while Chinese horror has immense potential, positive reviews and interests don’t always translate to significant commercial success. “Chinese horror games can quickly gain mainstream attention, but the sales don’t always live up to that buzz,” Xu says, and she’s not wrong. According to video game press Gamersky, Firework, which ranked 12th in the top 20 Chinese games of 2021 with a 98 percent approval rating on Steam, sold only 270,000 copies. In contrast, other games on the list, such as NetEase’s battle royale game Naraka: Bladepoint (2021), sold 7 million, while the wuxia-inspired Tale of Immortal (2021) sold 3.9 million.

According to Xu, the sales ceiling for Chinese horror games is around two million copies, half of what is seen in other genres. She attributes this to their generally higher skill threshold and linear gameplay, which tends to lack replayability. Then there’s the fact that “many people might not dare to play; they might watch a few [clips of others playing] while having dinner, either alone or with friends—in essence, they’ll watch but won’t buy the game,” she says, comparing it to other game categories, such as card games, where players can repeatedly “jump in for a quick match anytime.” Nevertheless, Xu remains optimistic about the industry, pointing to passionate audiences who are repeatedly drawn to games’ storylines, promoting them on their own on social media pages.

Promotion is one element that continues to hold developers back, Xu says. “Many [Chinese horror game development teams] are made up of just one or two people, and they often don’t know how to handle promotion, how to launch on Steam, how to communicate with the media, or how to engage with players. They also lack the resources to conduct player testing and other essential tasks.”

Recognizing the challenges indie developers face due to censorship and limited resources, Xu’s company Gamera Games launched initiatives like the Chlorophyll Program, whereby the publisher helps to distribute a game but only takes a cut from the developer on sales over 10,000 units. “Even if a developer’s current work has limited commercial prospects, we’re still willing to help with promotion. This is where we hope to step in—to help solve these challenges and support them in their journey,” adds Xu. Over the years, the 32-year-old has signed dozens of horror titles, including Paranormal HK, Firework, Sanfu (2023), Black Sheep, and Laughing to Die. “I don’t aim to exclusively sign horror games on purpose—I’m always looking for great stories. It just happens that some great stories are told through horror games.”

Gamera Games has since been affectionately dubbed “the publisher from the underworld” by fans for releasing dozens of horror game hits. It even hosted a horror game party in Shanghai during Halloween 2020. At the event, developers, players, and livestreamers shared their backgrounds, introduced their games, and bonded over their shared love for the genre.

Xu believes that the essence of horror shouldn’t be confined to the supernatural, and she’s eager for new ideas to emerge in the industry. “Most people tend to define [Chinese horror] in terms of ghosts, the supernatural, and folklore. But I believe that Chinese-style horror encompasses so much more,” she says.

For Xu, drawing on fresh yet relatable content is the key to success in future Chinese horror games. She cites films like Lost in the Stars (2023), which highlights the vulnerability of women within traditional marital relationships, and Korea’s Door Lock (2018), which sheds light on the challenges facing women living alone. “The fear of getting married, having children, working overtime, or dealing with unemployment—these are things that scare us, the horrors that exist in our everyday lives. There’s so much more to explore.”