During a rural Chinese family reunion after the Lunar New Year, a man and his pigs became the unexpected center of attention

No cars were coming from the opposite direction, so the Mercedes and the Nissan that followed it glided into the village and parked on the cement pad in front of the house.

The people who got off split into two groups: one that followed Ah-jun into the mountains and another that went inside. The second group had to wait for the first to return before they could fill their stomachs together. They had announced that they wanted nothing more than plain rice porridge paired with homemade pickled vegetables: mustard greens, pulled from an earthen jar after fermenting for two weeks or so. Those who went up the mountain were to check on pigs. They had been told about a herd occupying one of the peaks—apparently part of Ah-jun’s latest moneymaking scheme.

“You need a place of your own,” said Lao Gao, Ah-jun’s uncle, leaning back in a rocking chair. He was talking about the house in which they were seated and addressing his second daughter, seated across from him on a wooden sofa. “Have a good look, Ah-pin,” he said.

It was Lao Gao who decided to knock down the old house and rebuild it. He made sure to return to the village during holidays like Qingming and the Lunar New Year, or for weddings and funerals. It wasn’t always convenient to find a place to stay, even with relatives. But now if he wanted to, he could stay for two nights and a day in his own house, comforted by the cooing of the quails outside the window and smelling the fragrance of the paddies.

His second daughter’s husband, however, hadn’t been able to do the same in his home village, as he had given up the old house to his three younger brothers three years earlier. Now, no matter how Ah-pin complained or patiently remonstrated, there was no way to return to life among the fields and the warmth of sisters-in-law. When Ah-pin and her husband went to visit, they returned home the same day. The old home would only tolerate that small kindness.

Explore more short stories set in rural China:

- Countryside Police Station: An Unsolved Case | Short Story

- Spring Days Past | Short Story

- Hi-Lee-Bon | Fiction

“Without a house,” Lao Gao said, “visiting becomes a chore.”

After he quit smoking, if he wasn’t talking, Lao Gao was always staring at his phone. The characters that ran across the screen were big enough to suit him, and there were always videos from different sources to flick through. This was the third time Lao Gao had quit smoking. Now, he wrapped his arms tightly around himself, with a phone his son had recently discarded precariously balanced in his left breast pocket.

Ah-pin gave her husband a look and changed the subject to their younger cousin, Ah-jun, who had once planned to build a house for his family in the county seat. “That fast food shop he opened on the edge of Dongguan was never short of customers, with a factory on one side and a school for workers’ children on the other. Business was good. When Ah-jun’s wife Ah-jing got pregnant with their second child, Ah-jun started thinking about coming back, buying some land in the county seat, and building a house. Ah-jing thought they were going to have a son. He thought it would be good to get settled.”

Someone else in the living room, Lao Gao’s lone daughter-in-law, spread her fingers over the heater.

“He called family members to help out at the fast food shop at first,” Ah-pin continued. “You know, it doesn’t take much training to be able to cook in one of those places. All that really matters is being able to get the food out the door as quickly as possible.”

The daughter-in-law stared at the backs of her hands, as if savoring the feeling of the heat penetrating her skin.

“Anyway, they soon sold the shop to someone. The child turned out to be a girl. The house was never built.”

The daughter-in-law leaned down to adjust the setting on the heater.

“He was still borrowing money from Dad back then,” Ah-pin said, referring to Lao Gao. Then she added, suddenly remembering something she had heard: “He didn’t have enough money, yet he wants to build a house—only a few thousand...” She sat down firmly and comfortably beside her husband.

The winter before, they had been using a charcoal brazier to keep the place warm.

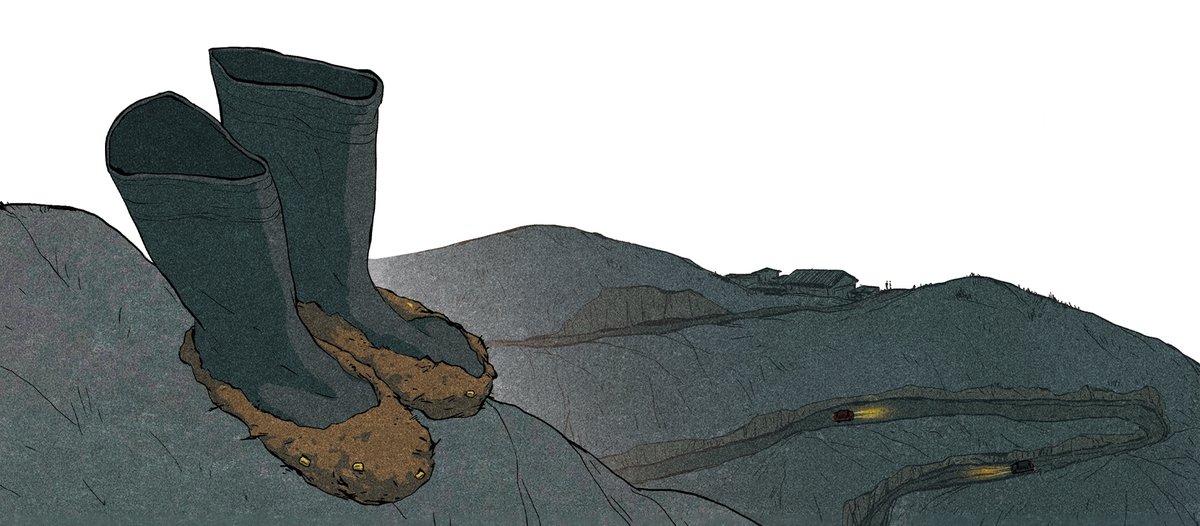

Ah-jun’s rubber boots were streaked with mud and their soles coated with clay. His legs were skinny, so the boots swayed left to right, giving the impression that he was shuddering. Ah-jun shoved his left hand into his pocket and stepped in front of them.

“It might take me fifteen minutes,” he said, “but I’ll budget forty minutes for the rest of you.” He turned and began to walk, not looking back.

The distance between him and the group increased.

Among those lagging behind were Lao Gao’s younger sister (Ah-jun’s aunt) and her son (Ah-jun’s male cousin). There was also Ah-juan, Lao Gao’s youngest daughter (Ah-jun’s cousin). Both cousins were older than Ah-jun. They also brought their partners and children. Their significant others were not fluent in the local dialect, and so, naturally, the children, too, spoke Putonghua. Their gloriously standard speech flew joyously around the highlands. Ah-jun understood their every word.

On the left side of the mountain road was a row of homes belonging to villagers. A young man had brought a portable stereo into the open space in front of one of the houses, and a moving melody sent Cantonese lyrics up toward the peaks.

“Isn’t that Wenzhi? And that’s your brother, Wencheng, isn’t it?” Ah-juan looked over. “I can’t tell the boys apart,” she said.

She and the boys in the yard shared a surname.

“Sister,” the boys called to her, “it’s been a while! Sit and rest awhile?” Their manners were impeccable, and they were genuinely happy to see her.

“No,” she said, “we’re going up into the mountains to see Ah-jun’s pigs.”

Ah-juan’s expression was slightly stiff. She struggled as time went by to mimic the cheerful faces that had come naturally when she was in her 20s. Then, she had no children, nobody to look after, and men were pursuing her. Those days and her cheerful expression were both long gone.

She didn’t recognize some of the people in the yard. They were dressed fashionably. They were decorated in bright, variegated colors. They were still young.

“Bossman, when are you going back to Macau?”

It was the one named Wenzhi who replied. He licked his lips, smiled, and said, “Hard to say! The pandemic situation still isn’t clear. I’ll know better once we get through to the end of the year.” He stood, swathed in the beats from the stereo.

Ah-jun walked on without taking further notice of the distraction. Soon, he was out of sight.

Perhaps affected by the music, the group behind A-jun started to enthusiastically identify residents of the houses on the left, recalling silly stories that had happened among them and filling the mountain air with crisp laughter. At the same time, they were busy figuring out the names of the mountain ridges beyond the fields on the right and recollecting the names of flowers and plants. They corrected and instructed each other, and reminisced:

“I used to think those mountains were so tall, and so far away, but now I realize how small they really are.”

“Even if these hills look smaller now, I can’t rush up them like I once did.”

It went on like that. Ah-jun felt as if he had heard it all before. There was nothing for him to say. They could forget about him. They could completely envelop him. But this was the first time that he had brought a group up the mountain.

They were looking forward to seeing the pigs. He was looking after the pigs. He was caught in their gaze. The villages faded. The flatlands that contained the few fields were replaced by hills. The fields meant food. The fields meant struggling to fill one’s belly. The future was unknown. The future belonged to Ah-jun and his children.

At that moment, they were going higher again. The road had ups and downs. That was how mountain roads were.

Ah-jun’s aunt pointed out a cave beside the road.

“Years ago,” she told the group, “people looking for gold dug out the hillside bit by bit.” She had been young in those years and still lived in the hills back then.

If she had not said anything, the narrow rectangular opening, which looked barely big enough to permit a dog to scramble inside, would have escaped their notice. Since humans had tools, they began to dig, whether because they were bored, or they had no work, or for some other reason, but none of the group was particularly interested in the excavation. From the outside, the hole looked as if it might only be half a meter deep. The hole narrowed as it went deeper, so eventually you would only be able to wriggle through it. That was impossible to know from looking at the entrance.

“If anybody ever struck it rich in there, you wouldn’t know,” Ah-juan’s husband finally spoke up.

He moved closer to the cave. The gloom made his face feel tight. He shouted and the echo came back to him, deep and clear. He had to admit that it scared him. The darkness of the entrance was unaltered. The walls sounded solid.

He stepped back onto the road, shaking a piece of mud off his boot.

Far from the village, all that was left was the bright yellow soil, as well as the neatly arranged trees of the production forest, stocked with pine, eucalyptus, firs, and anise, all appearing underdeveloped. The clouds, looking like stretched cotton wool, hung low with gray-blue moisture, with enough coverage to still block most of the sun in the western sky.

The hikers started complaining about their phone signals going out.

“In the beginning, Ah-jun was raising ducks. In the end, it was goats,” Huaying, Lao Gao’s wife, came out of the kitchen telling her children about her nephew. “The shed your father built for the goats is still at the foot of the mountain, up where the pigs are.” Her lower back gave out and she had to put a hand to the wall to steady herself. She was waiting for the pickled vegetables to be delivered.

“Those ducks were skinnier than him,” Lao Gao quipped, and everyone laughed.

There was a paddy field across from the house. Over the years, most of the houses in the village had been renovated and made taller, so it was no longer possible to see it. Paddy fields occupied valuable stretches of flatland, and they tended to be shallow and narrow, so that even the ducks struggled to stretch their wings or find food in them. If ducks don’t receive sufficient nutrition, they start to grow thin, and they stop laying eggs. Ah-jun tried his best to earn some profit from them while he could. Back then, Ah-jun drove a Mitsubishi motorcycle. He brought two of the ducks to Lao Gao’s house.

“Some rare generosity!“ Huaying chuckled.

“Two ducks stewed in a pot, and we had to add a few more dishes ourselves to feed the family,” Lao Gao’s daughter-in-law said. She always spoke in a loud, clear voice. As soon as the pickled vegetables arrived, she would stir-fry them with oil. She had replaced Huaying as the person in charge of the kitchen. There was already rice porridge in the pot, and it would soon boil.

“In the end, it comes down to a lack of skill. It’s brute force,” Ah-pin’s husband said.

“Goats are the same. One dies every now and again, and there’s nothing you can do about it. Some of them get sick. Some of them eat themselves to death. The grass up in the hills is rich. The goats don’t know when to stop eating.” Lao Gao straightened his back. It was a habit that had stuck with him even after he left the military.

“All his animals were free-range. I bet he wishes he could skip the hard work and count the money,” Huaying came out of the door. She squeezed the frame tightly with her fingers. “Count them as they come...Too lazy.” She saw Ah-jing, Ah-jun’s wife, trotting toward her.

“Is that enough?” Ah-jing held pickled vegetables with both hands. She called to Lao Gao.

“You’re back,” she smiled again at everyone.

Huaying motioned for her to bring the pickled vegetables into the kitchen.

“If it’s not enough, just let me know. I have plenty at home.” Ah-jing put the pickled vegetables on the stovetop and quickly went out again. Her son was asleep in a sling on her back.

“I heard there are three goats left. He set them free up in the hills,” Lao Gao rubbed the outside of his arm. He had very few habitual movements. “You run into them up there sometimes. But sometimes you don’t see them, even if you go looking.”

“And then he remembered the pigs. You can only hold so much mountain for yourself,” Ah-pin guessed blindly. She regretted not going up into the mountains.

“He’s already thinking about getting rid of them.” Compared to the conversation, Lao Gao’s sigh was energetic.

“What’s going on with the pigs?”

“They won’t be sold for a good price. The price of the meat isn’t as high as it would have been when he first got them.”

“Let me have a look. I remember he posted about it before,” Ah-pin looked through Ah-jun’s WeChat Moments. “Mountain-raised pigs. Belly, nineteen per jin. Hind leg, seventeen. Ribs, twenty-seven. Trotters, twenty. Liver, fifteen. Heart, eighteen. Tongue, fifteen…It’s a bit expensive, isn’t it?” She thought of her own pitiful but reliable wages.

“Try to follow the market and you’ll always be a step behind,” Ah-pin’s husband opened a candlestick chart on his phone. Spending the day in transit, he hadn’t had a good chance to look at it. “You need to grit your teeth, and you need to know the right moves, or you’re doomed.” He furrowed his brow, not only because of the tiny figures on the screen, but also to focus his aging eyes.

“What then? What comes after the pigs? I figure he’s going to build a zoo,” Ah-pin walked into the kitchen. She paced. She liked the feeling she got when the family came together, whatever they were doing, and whatever they were chatting about.

“Xiaoliang didn’t come?” Ah-jun was standing in a rain shelter at the foot of the mountain, waiting for the group to pick their way downhill. They were on the last stretch.

“He’s in Hunan. He went back to work on the third day after the Chinese New Year,” his aunt panted. She asked how much farther it would be. Her knees were about to give out.

“Just halfway up the mountain. A few twists and turns,” Ah-jun smiled at them for the first time. He stuck one hand in his pocket. In his other hand, he held an almost-finished cigarette.

Ah-jun said, “I’ve never seen him this eager to work.” He bit the tip of the cigarette and kept walking up the trail.

“He’s still quite lazy,” his aunt pinched her knees. She had decided to rest a while longer under the rain shelter.

Everyone hung their coats on their arms. The heat was painful. It also gave them a sense of unfamiliar cheer. They looked at the dark blue tarp over the rain shelter, but they weren’t sure what it was for. Nobody spoke.

In his family, Ah-jun was closest to his younger cousin, Xiaoliang. They were about the same age. Xiaoliang was born in the county seat, and Ah-jun was born in the countryside. Xiaoliang loved soccer. He would stay up all night to catch Manchester United matches. Both of them loved betting on games. This behavior seemed harmless for Xiaoliang, or an outgrowth of his love of soccer. But to Ah-jun, it was purely for money. He once put all his cash into betting on soccer, trusting Xiaoliang’s experience and expertise—this was after he became exasperated with Mark Six, the classic Hong Kong lottery game.

He fantasized about what their lives would be like once they struck it rich. Xiaoliang would move himself up from a stall underground in a block of computer stores in Nanning to a shop on the first floor with a glowing sign, hiring several employees. Ah-jun would open a chain store in Guangdong, something connected to renovation or catering. He would also have a dedicated team.

But now, he was nothing more than a father of four, with over 150 swine. Xiaoliang had two kids, both boys. He was growing heavy. The year before, Xiaoliang told Ah-jun that he wanted to go to Hunan. One of his high school classmates was running a filling station. He was going to help out. There would be steady wages, finally. They rarely talked about money or business. Unless necessary, they rarely talked at all. Maybe that was the way that true friendships or familial ties developed.

Ah-juan said, “Auntie, your roots are turning white.” They started walking again. Ah-juan, supporting her aunt, walked at the back of the line.

Ah-juan was a few months older than Ah-jun. She worked as a mid-level manager at a property firm in Nanning. She relied on her local husband’s wits to get by.

“It started a long time ago. If I don’t dye it, it goes completely gray,” her aunt shook her head. She looked up at the mountain, which seemed then not to rise quite so high. “Same as your father. Thick hair. But once we go gray, it goes something fierce. Your grandfather had thick hair, too. You might not remember much about him.” All that she could see were the crowns of the trees. “These days, I just don’t have the strength.” She was not sure whether it was the pigs she wanted to see, or if she simply wanted to walk a trail that she had walked before. She realized that she was already on the trail she wanted to take.

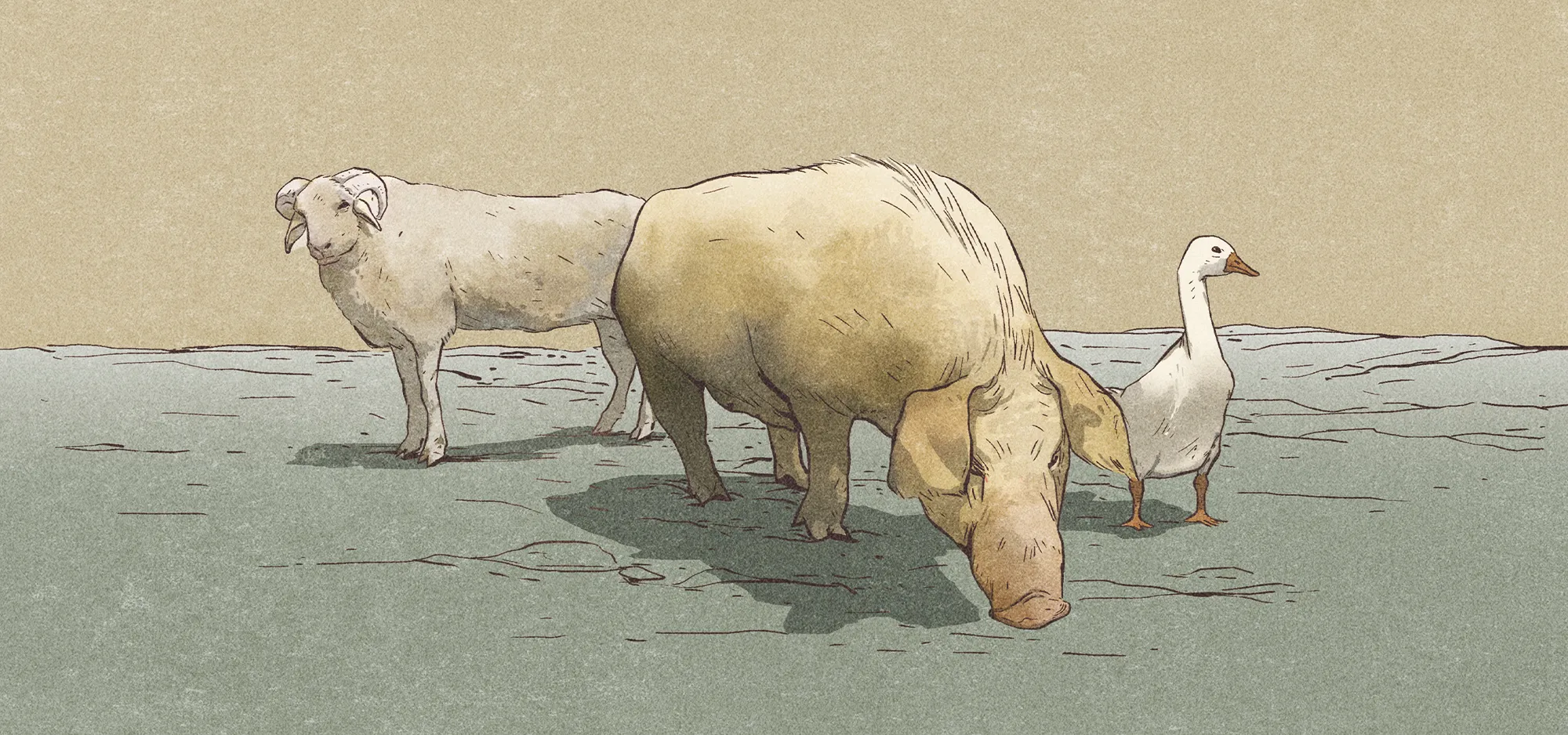

The children ran ahead of Ah-jun. They were sniffling and yelling, but they never seemed to tire. They ran into a pig coming down the hill. It was a full-grown sow. She was only interested in Ah-jun. The sow struggled to turn, its tail wagging wildly. Ah-jun patted the pig’s head, then stuck his hand back in his pocket. The back end of the pig continued gyrating.

Ah-jun’s young nephew said, “She’s got so many breasts!“

There was scattered laughter in the valley. The sound of grunting became louder.

Ah-jun’s male cousin said, “They must’ve gotten hungry up here. They look like they’re ready to come off the mountain and go begging for food.”

The curving trail made them feel as if they were concealed in a forest. If you walked a few steps away from the group, it was as if you were alone. The occasional sound of a branch swaying or creaking was enough to set you on edge. The sky was still light, so they had lots of time to admire the pigs. Unconsciously, their pace slowed, and the group came together again. Ahead of them, Ah-jun disappeared.

The sow walked slowly, but nobody dared get too close. Her snout was longer than those of domestic pigs, and the lines of the muscles in her hindquarters were more defined. At this moment, seeing this didn’t whet any appetite. The sow’s face showed no emotion. Her body gave off a foul odor. It was impossible not to note the many nipples dangling from her udders.

They followed the sow. She was not a reliable leader. Fortunately, there was no fork in the trail. They felt that Ah-jun should not have raced ahead of them.

“They dumped their daughter Ningning on us, then he and Ah-jing went down to Guangdong. Two years—and not a bit of money came our way from them. They didn’t care about the kid, either. They figured, as long as she had a table for dinner and a place to lie down after, there was nothing else for them to worry about,” Huaying took a seat on the stool that her daughter brought to her. She wanted to be closer to the heater.

Ah-pin said, “If you make a living running your mouth, everything seems to come easy.”

“Your father doesn’t want me to say anything,” Huaying decided to keep her gaze fixed on the imitation brazier.

“What is there to say?” Lao Gao’s tone rose sharply. “If they want to leave, let them. Are you going to send the kid away?” Lao Gao only raised his voice when he was with Huaying and his eldest daughter. His eldest daughter had not made the trip this time. She said she had to work overtime. Since her divorce, her days had been very full. She even went out some winter mornings to swim in a pond.

“If you didn’t come back, I wouldn’t bother opening my mouth. How many times have they borrowed money from Father!“ Huaying, standing beside her daughter-in-law, looked frail. “Father’s a soft touch. He’s lent a few thousand at a time, never with any plan on how he’s going to get it back. In principle, I shouldn’t even get involved.” From so many years spent as a teacher, her voice was husky and loud.

Lao Gao finally decided what the house lacked. He needed a television set. Next year, they could sit around watching TV and chatting. TV shows always provide something to talk about.

“He was working at the cement plant, at first, then your younger brother got him a job at the police station. But before all that, he went to Macau with Wenzhi to do renovation work,” Huaying decided she needed to state clearly Ah-jun’s situation.

“If you want to get ahead doing those sorts of odd jobs, you need to stick with it,” Ah-pin’s husband said. “Even doing manual labor, you need to use your head.” The screen of his phone, pressed against this thigh, glowed. His gaze rested somewhere beyond the house.

“He was taking advantage of people over there. The other party said they wouldn’t let him leave, and they refused to do business with anyone from our village. He shamed the entire village, maybe even the entire province. That’s why he decided to stay there,” Huaying usually didn’t have so much to say, but she felt the time was right. “When he was there, he met a Chaozhou girl who was working at a hotel. When it was time to come back, he came to stay with us, instead of going home. Back then, there was no road to the village, as you know, so you had to take a ferry across the river, then there was a half-hour walk. I picked up a call from that woman, and she asked for ‘Ah-gun.’ That’s what she called him. I thought to myself, he was not going home at all. In the end, they couldn’t make it work. If they knew what each other had going on back home, it would have ended even sooner.” Huaying felt as if her palms and her soles were impossible to warm.

Someone came through the door. It was Ah-jun’s father. He nodded to everyone. His face wore a broad smile. Ah-jun took after his father. That was clear when he spoke and when he laughed. The whole family was like that.

In his hand, Ah-jun’s father held a cigarette. He tucked the Double Happiness cigarette behind his ear. Ah-pin’s husband asked about Ah-jun’s current situation. They had never been shy about discussing Ah-jun in front of his father. He was an easy person to chat about. Nobody feared sullying his name.

“Hell if I know! When he’s home, that’s where he is,” he smiled as he spoke. With so many places to sit, he still chose to stand. “We only have the barest notion of what he was up to when he wasn’t at home.” Ah-jun’s father’s home was next door. That was where they had always lived. They had recently built a three-story house on the old lot. They had one more floor than their neighbors, but they had not put up tiles on its exterior walls.

Ah-pin’s husband said, “He should know better by now.” He glanced at his phone. “He’s a father, with four kids. Does he want another one?”

“He’s got a boy now, so he’s probably done. But who knows?” Huaying tried to smile, but she grimaced instead. It is hard for the faces of old people to conceal their emotions.

Ah-jun’s father put the cigarette to his lips. No matter the brand, he could still puff as he always had. He tucked the cigarette in his lips. He paced, then went out the door, trailing smoke. The TV was still on next door. Lao Gao’s throat twitched. He would not look at his cousin.

“One word: lazy!“ Ah-pin cracked a melon seed in her front teeth. When she was at home, she was never this unoccupied. “No matter how many wicked little tricks he comes with, he’ll never even break even.”

“He lives off the good names of other people. He’s just not...how do I put it? He’s just not a dependable person. He likes to waste his time fooling around. How is a man of his age and such a shameful character going to turn out?” their daughter-in-law had a lot to say that day, too. Her daughter was away at university, and her husband was always busy with work, so she was always looking for the chance to speak. She was a mathematics teacher at a middle school. Her in-laws were quite pleased with her occupation. Even before their son, they had expressed great affection for her.

“Ah-you is too honest. He still hasn’t found a wife,” Huaying sighed. Her palms were finally growing warm. Ah-you was Ah-jun’s younger brother. He was a man who loved to laugh, whether he was talking or listening, no matter the mood. It might have been an unconscious twitch of his facial muscles, maybe a congenital trait.

“Years ago, I got him a job at the shoe factory. When I was on my way out, he was still making shoes,” Ah-pin’s husband’s cheeks were puffed up and shiny. “He couldn’t wait to burrow in there. He went from one shoe factory to another, from Dongguan to Guangzhou. You can’t race around like that.” He repeated himself: “If you’re working to death, any chance of a normal life becomes more and more slim. Some people work for a few years and then get a job in management.” He couldn’t help glancing at his son, who was curled in front of the dinner table. He was playing with his phone. He smiled to himself sometimes. They knew that he had met a girl, and she was waiting for him back in the city. He wasn’t interested in pigs. He spent his time staring at a phone or a computer, finding ways to make himself smile. They hoped he could make something of himself, and earn something from the state-run institution that he had fought so hard to get into.

“The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. His father has spent his whole life as a lazy bum. How is he going to change?” Huaying rose with difficulty. She leaned in the doorway again, stuck her head out, then pulled it in again. “Ah-jun’s mother, Caimei, has had epilepsy for 20 years now. She still has to get up and go to work. If one day she passed out in a ditch, let’s see if the old men would still laugh.” She bent her already crooked waist and lowered her voice. Her weak eyes blazed.

The color of the sky made everything slightly blurry. Dogs barked ceaselessly in the distance.

The pigs increased. There were big ones and small ones, light-colored and dark-colored, male and female, and almost all of them related in some way. They pressed against each other. They knew what it meant when they saw Ah-jun coming down the slope. The piglets kept to the margins, knowing they would not be able to press themselves into competition with the larger swine. Primordial intuition sent them clinging to their mothers’ teats. As they sensed the kernels of corn, the full-grown hogs surged clumsily, jerking forward fiercely, and crying out in loud, clear voices.

Ah-jun tossed the kernels. They fell like rain across the col. He scooped them with a ladle from a blood-colored bucket hung under a rain shelter. The sound of the metal ladle hitting the kernels was like chestnuts being tossed in a hot pan. The pigs raced to wherever Ah-jun tossed the kernels, marching like fierce and obedient troops. The soil in the area had been hardened by the trampling of the pigs. Apart from stones, there were also the remains of sacks of fertilizer.

“Did they get enough?” Ah-juan’s husband stood with his hands on his hips, each of his feet up on a rock.

The rest of them took pictures, shifting around to capture better angles. The children screeched madly.

Ah-jun told the children not to chase the piglets. The nursing sows would not tolerate agitation.

“Did you hear him?” Ah-juan snapped, then helped her sister-in-law shepherd the children to an appropriate location to take a group picture with the pigs.

Ah-juan said, “You should do a livestream. It will definitely be a hit.”

“I’ve already got my hands full,” Ah-jun replied.

His male cousin cut in, “That’s a woman’s opinion. You didn’t take care of the paperwork. The fines would make you weep. Just keep this quiet and make some money.”

The swine with dark spots were a variety called Bamaxiang. The white hogs were a local breed. Ah-juan called for Ah-jun. When Ah-jun was not speaking, his face went slack. He was doing the same thing he did every day. There were usually two feedings a day, but he sometimes got lazy and skipped the evening meal.

His aunt walked over and asked him, “Could the pigs run away?”

She tilted her head back and saw the dark shape of the mountain peak. It looked like a man. The shadow was darker and shorter than the fir trees around it, and it extended all the way to what seemed to be a mountain road.

“Is there a road over the mountain?” his aunt seemed on the verge of shouting.

“Mojia village is right over there,” Ah-jun put another cigarette on his lips. “One glance, you can tell which ones are going to slaughter.”

Sometimes he cast the kernels from the ladle, and sometimes he tossed them. They rained on the backs of the pigs. The pigs had longer hair than domestic pigs. They were skinnier. They were rapidly evolving, or perhaps regressing. Their long snouts were perfect for getting at the kernels that fell into the cracks between the crushed stone.

“They only eat a few kernels each. It won’t be easy to fatten them up.” The male cousin watched two swine falling into the undergrowth while fighting over the grain, and he tried to contain his excitement.

“You don’t have to worry about each of them getting their fair share!“ Ah-juan’s husband’s voice cracked. “The law of the jungle rules here.” He took a few steps back to avoid one of the boars that was coming for the kernels of corn scattered at his feet.

Ah-jun took down a sickle that was stuck in a tree trunk. He hacked some branches down from a duck’s-foot tree. The swine swarmed the leaves, their mouths open wide.

A child cried, “The pigs will eat anything!“ Ah-juan advised her son to remember the scene, so he could put it in his winter vacation diary.

“Do you see the ones with darker hides and pointed ears? They weren’t part of the plan,” Ah-jun laughed, finally. “Those are wild boars. You should write about them, too.” He chuckled happily to himself and stuck the sickle back in the tree. It was a fast-growing eucalyptus.

Lao Gao’s lone daughter-in-law fried up two dishes of pickled vegetables. On one of them, she sprinkled chilies. Most of the people here loved spice. The dish without chilies was for Lao Gao. Since his surgery the year before, it had become more troublesome to look after him. Nobody hated that more than Lao Gao himself. Except for those in the very oldest generation, everyone, including the children, served their own rice porridge.

“Something to cut the oil,” Ah-pin’s husband took a fearsome slurp of porridge and then exhaled heavily.

A sheet of newspaper was put down, and the steel pot was placed on top. The porridge bubbled out white steam.

Ah-pin joined in, “I came back just for this, some rice porridge and pickled vegetables...” She chose to stand while eating, holding the bowl in her hands.

As people came down from the mountain, the living room became hectic.

“How did the pigs look?” Ah-pin asked.

The children, caught up in their own affairs, ignored her.

Ah-jun didn’t return. A more complicated dinner than rice porridge and pickled vegetables was being prepared next door in his own home. Ah-jun’s father had stood in his doorway and invited everyone over, but they knew it was mere courtesy. A big pot of porridge awaited them in Lao Gao’s house, after all.

“Our Fourth Uncle is quite considerate,” Ah-pin said, referring to Ah-jun’s father. “As far back as I can remember, he was always smiling. I was even younger than Ningning now. We lived together back then, Ah-jun’s family and mine. We lived here. That was when Grandfather was still around.”

“If I could be a lazy bum, my cheeks would get sore from smiling,” Huaying had become much more direct in recent years. “It’s only natural!”

Everyone began chatting. They mentioned the abandoned mine. Ah-pin told them that she had sometimes gone into the mountains when she was in primary school, and had gone once into the cave.

Lao Gao said, “Two-seven-four. That was the number they gave that mine. They put up plank houses near the playground beside the village administration office. It was mostly miners living in them, and a few engineers, some of them single, some of them already married with kids. There are mines all through these mountains. They found gold around the time of liberation. Things were going strong in the 1960s, but they were done by the 70s.” He put down his bowl and chopsticks.

“I remember, some people in the village called the guys ‘two-seven-fours,’ or ‘gold bugs.’” Ah-pin’s eyelashes fluttered. “They were taller than any of us. They spoke Mandarin.”

“People in the village were chasing them around, trying to get at the gold themselves. I did it, too. Some guy wound up panning out a few jin of gold,” Lao Gao barely suppressed a smile. He remembered more than he said. “When they took what they could out of that lode, there was nothing but dirt left. They left, one after another. There’s nothing left up there but the hole in the side of the mountain.”

“When we were coming down, Ah-jun said that a pig got in there once,” Ah-juan’s face was serious, or maybe she was simply exhausted. “Can you imagine a pig going into a mine? He said he saw it himself—the pig sticking its head out of the hole.”

Lao Gao’s younger sister—Ah-jun’s aunt—was still worried about the pigs going missing on the mountain. She didn’t think they would get lost, but that they could be stolen by someone, like the people from Mojia village. They thought about the goats he had raised before, and the ducks. They had come to terrible ends. Their fate was tied to that of Ah-jun’s.

Ah-juan was curious about where Ah-jun slaughtered the pigs. She was also curious about how he was going to sell them.

“Here,” Huaying motioned to the yard with her chopsticks. “He bleeds them first, then scorches the hair off them. He takes the guts out of them, then puts them up on an iron frame. Right out there. You need two iron hooks for the head.” The two cars were parked over the site of the slaughter.

“The knife for slaughtering pigs is as sharp as a dagger. It opens them up like a zipper,” Huaying mimicked the single stroke with her chopsticks. “Didn’t you ever see it when you were a girl?”

“Don’t you follow Ah-jun’s WeChat Moments? They portion out the swine in the comments,” Ah-pin chewed her pickled mustard greens loudly. “Not everyone’s got mountain-raised pigs.”

One of the children began to sob, but then quickly burst out laughing again. The children raced together out the door.

The sky overhead was packed with stars.

“The stars are crying. Every time they twinkle, you can hear them.”

“Idiot! All you can hear is the insects buzzing and the pigs grunting up on the mountain.”

Neither child would concede their position. After a while, one of them started barking, mimicking the village stray, and the other followed. There were more sounds to be heard in the village at night than during the day, as long as you listened carefully.

By the time Lao Gao took his phone from his pocket, it was already time to get back in the car for the drive home.

Ah-jun emerged from next door to see them off. As usual, his hands were stuck in his pockets. He had changed from his rubber boots to flip-flops.

Ah-pin’s husband asked him, “You definitely need to save some money in the new year, right?”

They told him to set a good example. Some of them sounded as if they were encouraging him. Some of them sounded as if they were giving him grave advice. Ah-jun hadn’t come over earlier, or there would have been many things to talk to him about—some they had covered before, and some that were new.

Ah-jun only laughed. When he laughed he shrugged his shoulders just like his father.

They distributed red paper envelopes of money to the children of relatives. The parents of those children not present took the red envelopes for them. Everyone skipped over Ah-jun and gave their envelopes to his wife Ah-jing. After that, the cars were started up.

Ah-jun shuffled over to the front of the house and crouched there, his hands on his knees, his shoulders low. Smoke drifted between his mouth and his palms. The headlights of the cars chased each other between the ridges of the mountains, then finally disappeared, along with the barking of the dogs.

Ah-jun could still feel on his backside the warmth of the cars coming up from the concrete. That was the only thing unusual about the night. He couldn’t hold on to the heat. He needed something much bigger.

Back in the county seat, the excitement in Lao Gao’s family lasted until the sixth day of the New Year. After that, people started leaving, setting out for the cities where they lived. As for Ah-jun, how long he crouched in the yard and what he was thinking that night, neither his father nor Ah-jing knew, and he soon forgot.

Nights in a mountain village put people to sleep soundly and quickly.

Author’s Note: I’m not sure when it started, but a person’s success or failure is now determined by their wealth. But is this the only value system and worldview we have? On the night in the mountain village where this story unfolds, this is something worth contemplating and reflecting on.

What Comes After the Pigs? | Fiction is a story from our issue, “New Game.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.