Shanxi province is home to a staggering number of temples and other cultural sites, yet many remain in disrepair despite being key to local tourism campaigns

We’ve arrived at seemingly the wrong time. It is a rainy mid-October day, with little sunshine forecasted in the next three days. My friend and I are on a temple tour and we have discovered that Tiefo Temple, one of the city’s most popular attractions, will be closed for “maintenance” for the entire week. This is after it received nearly 20,000 people during the weeklong National Day holiday, most of them queued for hours just to have a peek at the temple’s 27 famous iron-structured sculptures from the 16th century.

I can’t help but feel regret and worry after this ominous start. This year marks the first time in several decades that Tiefo has opened to the public, and it remains unknown whether it can handle the hordes of tourists it’s received. (As of the time of publication, Tiefo is open again, though its future as a tourist destination is uncertain.)

But not all is lost. There is much else to see in Jincheng, Shanxi province, with its 6,601 cultural sites, including 72 national heritage sites and more than 700 provincial and municipal ones, typically featuring centuries-old architecture and artwork like sculptures and murals. The city is only 9,490 square kilometers, meaning there are two cultural sites for every three square kilometers. Many were opened in August, after the video game Black Myth: Wukong brought national attention to the city by featuring four of its temples, including Tiefo.

The city is trying its best to adapt to this newfound fame. The extra revenue is good, but people are still figuring out the proper balance between sightseeing and preservation.

The “museum” of ancient China

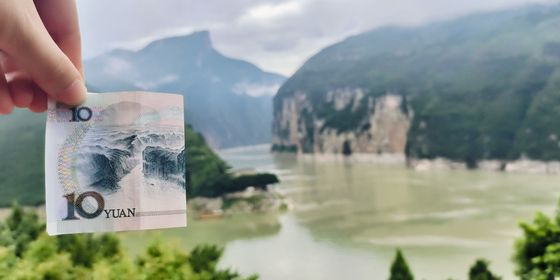

Shanxi province in northern China is known as the “treasury of ancient Chinese architecture.” The buildings are naturally preserved by surrounding mountains that block precipitation, which could otherwise erode ancient structures. According to a national survey conducted between 2007 and 2011, the province hosts 28,027 historical buildings (one-tenth of the country’s total), including the last three existing wooden buildings from the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), plus nearly 70 percent of the wooden buildings from the Song (960 – 1279) and Jin (1125 – 1245) dynasties. Of the 36 major scenes in Black Myth, a game loosely based on the Ming (1368 – 1644) dynasty fantasy classic Journey to the West, 27 are based in Shanxi.

Read more about Shanxi:

- New Goal for Coal: The Struggle to Repurpose China’s Abandoned Mines

- Catch a Sunrise Before Time at China’s Oldest Observatory

- Right to Roam: Trekking China’s Old “Western Frontier”

Jincheng has also been dubbed a “museum of ancient Chinese architecture,” housing 58 wooden buildings from the Song and Jin dynasties, accounting for one-third of the total number in the country. Often, one temple can serve as its own museum, featuring architecture from the Song, Jin, Ming, or Qing (1616 – 1911). Buildings might show signs of repairwork and renovations from each of these periods.

We might not have gotten out to the best start, but in three days, we ended up visiting 10 temples out of the city’s 63 recognized “national treasures.” They were scattered in different villages, some up in the mountains, difficult to get to, others in the city center. As we hopped from one site to another, I found myself traveling into history, getting lost in time, and feeling the divide between the ancient and modern melt away.

The useful gods

At 9 a.m. on the second day, we step into the courtyard of Xixi Erxian Temple in a valley surrounded by heavily forested mountains to see a spot featured in Black Myth. Several visitors are already there, surveying trees that look like animals: “That’s the tiger,” someone says.

“That’s the horse.”

“Where is the monkey?”

What they’re looking at are 1,200-year-old cypress trees whose burls look like the 12 Chinese zodiac animals when glimpsed at from different perspectives. Their origins remain a mystery, but they have long been one of this place’s major attractions. Though centuries-old or even millennia-old trees are common in Shanxi’s ancient temples, they can often distinguish themselves from each other in one way or another, just like the temples.

“This is the head, eyes, mouth,” a temple keeper, Xu Longfu, shows us with a laser pointer. The 69-year-old has worked here for over three decades, and is happy and proud to introduce the temple, from its history to every design detail, including the elaborate wood carvings of dragons, phoenixes, and cranes.

“An ancient temple such as this often took more than a decade to build, with quality materials,” Xu tells a visitor. They were built to last: The structures from the Song, Jin, and Yuan dynasties use a combination of pillars, beams, purlins, and other supports to create a frame that will keep the building upright even if the walls collapse.

These structures have preserved ancient beliefs as well. According to Xu, during each year’s temple fair on the 15th day of the fourth lunar month, thousands of people, mainly locals, descend upon the temple to pay respect and pray to the Erxian (二仙, “two gods” )—two filial sisters whose story emerged in the 8th century—for everything from rain to health to good luck in childbirth. In particular, families pray when their children turn 15 (or 12 in some places) for their “coming-of-age.” “The road [to the temple] has gradually improved over the last 15 years,” Xu says, “from dirt to concrete, and then to asphalt, to facilitate people’s visits.”

In addition to the “two gods,” Confucius and Laozi (the founder of Daoism) are also featured in different halls in the temple. Similarly, the Yuhuang Temple in Fucheng village, whose sculptures of 28 constellations went viral after being featured in Black Myth, honors gods in charge of the underworld and heaven, including the “Throat God (咽喉神),” worshipped by theater troupes, the “Ox King (牛王),” and “Horse King (马祖)” who are in charge of animals’ well-being. “Chinese people do not honor any useless gods,” as one folk saying goes.

When heritage comes with a price

When we arrive at Cuifujun Temple, which was established in honor of Cui Jue, an honest and upright official-turned-judge in the underworld, we are met with closed doors. It’s nap time for the keepers, we figure. So we take a break ourselves and search for food. We settle for a local favorite: instant noodles with meatballs. This region is famous for its handmade noodles, so why are instant noodles so popular? The stall owner, whose family has run the same business for nearly three decades, cannot say. Next to us, a local diner in her 70s cites its low price—only 7 yuan a bowl—and deliciousness.

Eventually, we get in touch with the temple keeper by phone. He lets us enter via a side door. Behind us, several other people file in. The keeper, surnamed Zhang, explains that the temple usually opens on weekends, but he makes himself available by appointment, partly because he’s afraid disgruntled sightseers might report him to the authorities.

The 56-year-old has mixed feelings about this ancient temple, earning only 10 yuan per day to oversee its operations, regardless of how many visitors come each day. According to several visitors from neighboring cities, Jincheng is the only place in Shanxi that doesn’t charge tickets to all of its heritage sites. Most temples don’t allow the purchase or burning of incense, either, in order to better preserve the timber-structured architecture.

But Zhang still takes pride in the Cuifujun Temple, which was first established in the Tang dynasty but was reconstructed in the Jin and renovated throughout the following eras. “My father had been its keeper since the 1980s, and I took over 20 years ago. I have deep feelings for every part of the temple,” Zhang says.

Many people of his generation were schooled in the village’s ancient temples, a common practice in the city decades ago. “Building schools was costly, so the villages used temples as schools until the 1980s, when the government started to attach importance to the preservation of such sites,” a local relic lover surnamed Zhao from a neighboring village recalls.

Many other locals share Zhang’s deep sense of pride in their region’s wealth of historical treasures. A middle-aged volunteer surnamed Wei in Jincheng’s Kaihua Temple tells us that this temple, like others in the province, is open in order to show the treasures “our ancestors have left.” He notices some young visitors taking photos and goes up to them to explain what they’re looking at before taking them around to see the centuries-old steles.

However, middle-aged and retired visitors, many traveling in tour groups, still made up the majority during my visit, as it was after the holiday season. A man surnamed Li, who runs a local car-renting service, speculates that authorities want to boost the local economy by attracting more young tourists with Black Myth-associated tourism campaigns, but it can be challenging to turn protected sites into ticket-based attractions with limited personnel. “You may have also noticed: The popularity [of Jincheng] has already faded,” Li says to us, pointing at the food street the government set up next to Fucheng village’s Yuhuang Temple just before the National Day holiday. Now, most of the stalls are closed.

The city, whose gross regional production mostly comes from its (state-owned) coal mining industry, has promoted “health and wellness tourism” over the last few years, though to mixed results. Li, personally, is not optimistic.

The maintenance of such sites is also costly. Zhao tells us that people in his village want to repair some of their temples whose walls are on the brink of collapse, but have only managed to raise around 800,000 yuan. According to a previous estimate, each square meter of one of these ancient walls can cost up to 7,000 yuan to repair. “Our ancestors have left us so many temples, but we’re unable to maintain them,” he sighs. “I feel shameful.”

A survey by Shanxi authorities in 2022 showed that over 80 percent of the province’s more than 50,000 relics at or lower than the municipal protection level needed repair, including around 1,800 damaged during heavy rains in October 2021. Repairing major sites is much more costly, requiring over 8 billion yuan.

I can sympathize with the relic enthusiast Zhao. His sentiment is part of the reason so many tourists go to Shanxi: to seize the chance to visit historical sites while they’re still there, with their centuries-old elegance and beauties, which is hard to replicate in modern times. I couldn’t help feeling wistful looking up at the 28 constellations inside Fucheng village’s Yuhuang Temple, where one of the original heads of the constellations was replaced after it was stolen in 2006. It’s not quite what it used to be, but it’s better than nothing.

New life for old relics?

According to Zhao, only the sites under governmental protection, especially the national ones, can get enough funding for maintenance. This is the case for Jidu Temple, which houses the “water god” who governs the Ji River, in Jiannan village. “Over 10 years ago, villagers tried to renovate the seriously damaged temple, but the money ran out just after building up the gate,” Zhao says. “Later, the national funds came in.”

Listed as a national protected site in 2013, the 8 million yuan “protective repair project” on Jidu Temple’s 20 or so buildings, covering an area of 3,000 square kilometers, took three years to complete, from 2017 to 2020. The local government announced the site’s reopening in October 2020, hailing it as “revived to its former splendor.”

But such efforts have not been without controversy. In 2018, the company in charge of renovating Jincheng’s Qinglian Temple caused a national outcry for “damaging” original historical and artistic elements by repainting the sculptures. The company argued it had followed the common rule of using the “original technique, skills, and material,” news media The Paper reported, but the public was not convinced.

Jincheng’s Kaihua Temple exhibits digital copies of its famous mural, which is over 88 square meters, featuring dazzling painting techniques from the Song dynasty, but this has also been met with criticism. During our stay there, several groups demanded the temple keeper open the door of the hall that hosts the original murals, saying the digital copies weren’t a sufficient substitute.

Meanwhile, the number of experienced craftsmen who know how to properly repair ancient buildings has been declining: More than 80 percent of practitioners nationwide are older than 50, while those younger than 35 account for only 4 percent, Sanlian Lifeweek magazine reported in July. Some authorities have taken measures to combat this. In May 2022, the Cultural Relics Bureau, the Education Department, and three other authorities of the province implemented measures to recruit and cultivate more than 600 professionals in relic preservation and research for the next five years. Their tuition and other fees would be paid for, and they would be guaranteed jobs at a local relic preservation center upon graduation. The government of Gaoping city, under the administration of Jincheng, has also started to replace old part-time temple keepers with better-paid full-time young employees.

But old heads such as Xu aren’t planning on going anywhere. He asserts that he’ll continue to work at Xixi Erxian Temple, as visitors enjoy his services, for at least the next three years. “As long as I’m healthy and have the gods’ blessing,” he adds.

On the last morning before we leave Jincheng, we visit the new Baima Temple, which sits on the ruins of a temple from the 15th century that was destroyed in the 1930s during the Second World War. It gained a new life in the 1990s with public donations. Jinggong Tower is the only remaining historical building there and is now a municipal protected site.

A loudspeaker is blasting how praying in the temple can grant people their wishes for everything from high test scores to job success to finding love on repeat when we arrive. Compared to the older temples, this one feels more touristy, with visitors of all ages, perhaps a bit artificial.

On our way downhill, we encounter many more people walking up to see the temple. That’s when an idea pops into my head: That building up there might, with its young architecture and relics, well be considered “treasures,” too, by those who come centuries after us—if they persist.

Photography by Jiayu Zhang (张佳羽)

Blessed by the Gods: A Tour of Shanxi’s Ancient Temples is a story from our issue, “New Game.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.