An imaginary Chinese village during the reform and opening up era, with its oft-referenced “Toon Street,” is vividly depicted in a newly translated short story collection from the author of “Raise the Red Lantern”

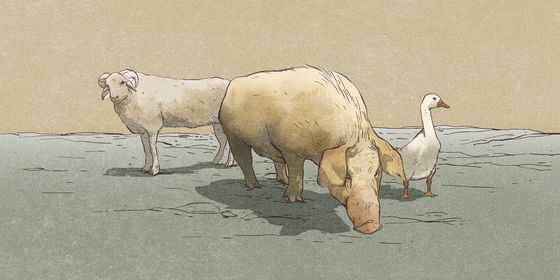

The first story in Su Tong’s Midnight Stories starts slow, with the feel of an old-timey fable: An old man in the countryside, like many old men in ancient Chinese stories, pines for an animal from the spirit world. But the story gets very real, very fast. The old man mutters a wish out loud—in order to avoid cremation, he wants to be carried off by a “white crane,” a metaphor for a natural death—and this prompts his grandson to carry out a frightening idea: The young boy begins digging a hole so that his grandfather can be buried in the earth, even if it means burying him alive.

The 10 short stories that make up Midnight Stories are like this, full of surprises arrived at slowly but logically, stepwise. That logic might only seem “surreal,” a word that has been associated with this collection, only because it is the logic of the Chinese countryside, a world that seems far removed from the China most of us are familiar with. How ironic that, in modern parlance, it’s this rural world—full of mystery and caprice—which is evoked by the phrase “real China,” as if we know anything about it.

Find more reviews of modern Chinese literature:

- Can Xue: The Experimental Voice of Chinese Literature

- Souls Left Behind: The Forgotten Chinese Heroes in WWI

- The Feminine Critique: Women and the Absent Men in Chinese Family Life

Su Tong knows. The renowned author—who wrote the 1989 novella Wives and Concubines, which gained international fame as Raise the Red Lantern, the title of Zhang Yimou’s Oscar-nominated film adaptation—mines the countryside, with all its possibilities for misunderstanding, violence, petty conflict, camaraderie, and jocularity, to its logical extreme. The collection is set in an unnamed river town somewhere in eastern China, with its central “Toon Street,” like a sandbox world in which dropped-in characters curse at one another—“I can see well enough to see you’re a black donkey”—joke at each other’s expense, spread rumors, run after buses, dream of fortune, and jostle for attention.

And what colorful, variegated characters, from catty schoolgirls to a half-blind old woman who tries to retrieve her murdered son’s skiff to a libertine poet-musician who says:

I was wrong about her, and I wronged myself, I don’t blame you all, I blame my own kidnapping.”

I was taken aback. “Who kidnapped you?”

He looked at me angrily, and suddenly howled: “Morality! And you hypocritical friends! You took advantage of my kindheartedness!”

Eventually, this character becomes a wine merchant who returns from New Zealand to attempt to open up China’s wine market. We are thus reminded that this collection is set during the late 70s and 80s, when anything seemed possible. The zeitgeist of that era—full of hustle and bustle, but plenty of confusion, heartbreak, and failure—is reflected in these tales, which seem magical because they are so realistic.

Ultimately, the world that Su Tong creates is one in which stories are celebrated, they are told and remembered. The narrator often changes, but the narrator is also often disembodied, and cites others—whether characters in the story or other disembodied villagers—when relaying the details of different scenes. As readers, we feel privileged to be able to listen in, like a fly on the wall, even when the stories stretch credulity. Of course, believability is not the point; these are stories etched into the collective memory of those on Toon Street, and they must be told for this ever-changing river town to be remembered—to exist.

There are some publishing errors in this book that I wish were cleaned up—missing punctuation, for instance—but one must tip the cap to Sinoist Books for bringing this collection to life. Translator Honey Watson deserves praise for capturing the patois of not just the characters, but the place. We are easily drawn in and happy to feel the dust on our feet, breathe the humidity, and shiver in the cold.

Where the translation really thrives is in the dialogue. The words feel both authentic and exacting, as if—for bilingual readers—you can hear the conversation in Chinese. Through their words, we get a sense of the characters’ eccentricities, but they never feel like caricatures of small-town people. I keep returning to this exchange between two characters in the story “Porcelain Factory Shuttle Bus,” who knew each other, though only briefly, when they were younger, and have a chance encounter many years later:

“What did he do? What did he do to get killed?” the older of the men asks as he exits the other’s car.

“You tell me! You tell me what he did!” the other replies. And then he drives off.

How simple, yet leaving so much to unpack. What we feel, in this exclamatory, is a decade of unresolved tension, of two lives lived radically different, and maybe a longer conversation that will never be had. It’s at this moment that we wish we could stay longer in this expansive world, stroll the streets like tourists, visit the herbal medicine shop, take a picture of the tower at the Children’s Palace, check out the riverbank—before it’s all gone.

The book only hints at this part, but it’s unquestionably there: the future, one in which skyscrapers have suddenly appeared, making old bus routes unrecognizable, a sign that the country’s breakneck growth will eventually erase much of what people knew. Maybe only stories will be spared—but even then, for how long?