Once again, she didn’t win the Nobel Prize in Literature—but at this point, her legacy may already be secured

Upon the announcement in early October that Han Kang, the Korean author of The Vegetarian, would take the Nobel Prize in Literature, fans of Chinese author Can Xue, who had been widely regarded as the front-runner for the honor for six consecutive years, were generally sanguine.

There was not much outrage—a feeling that might have been justified had the Swedish Academy chosen an obscure European septuagenarian. Can Xue will either win the prize eventually or join a hallowed list of snubs that includes Virginia Woolf and James Joyce.

It is impressive to witness a Chinese author of frightening and difficult literary fiction grow ever more well-known in a time of shortening attention spans, not to mention artistic and intellectual disconnection between global spheres. For a writer like Can Xue to achieve the level of literary fame necessary for editors of major newspapers to rush out annual articles on her feels improbable.

Many parts of Can Xue’s story are improbable, though.

Read more about Chinese female authors:

- The Feminine Critique: Women and the Absent Men in Chinese Family Life

- Forever Sanmao: Tracing the Legendary Writer’s Life in Gran Canaria

- Five Must-Read Works By Chinese Female Writers

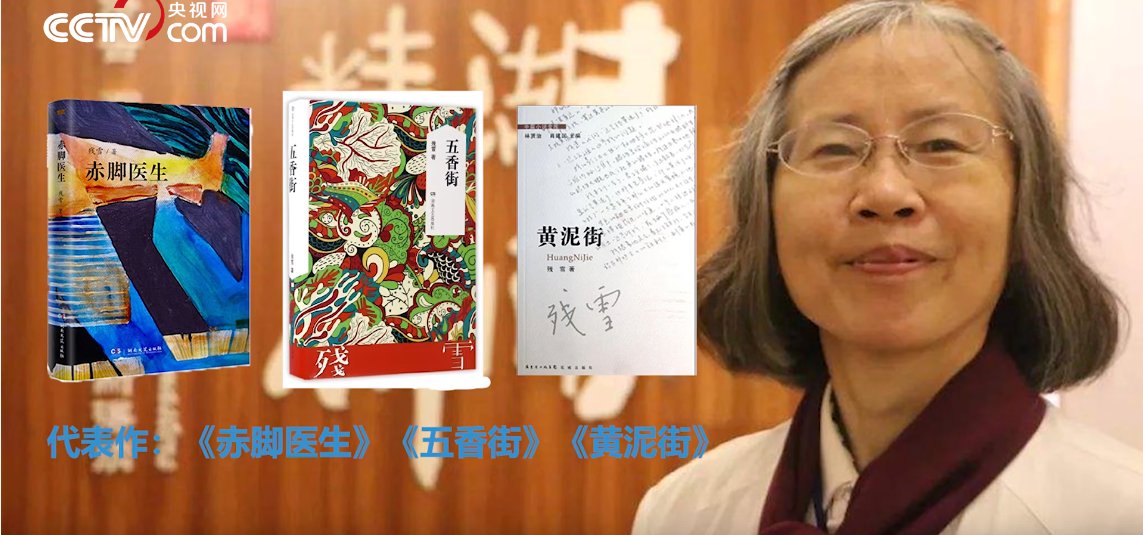

Born as Deng Zemei in 1953 in Hunan to journalist parents, Can Xue spent much of her childhood under the care of her grandmother. With no prospect for Can Xue to continue her education beyond primary school, she took the advice of her sister and began training as a barefoot doctor. She was still a teenager when she transferred work units to take a job at a metalworking shop.

She married her husband, Lu Yong in 1978. The couple started their tailoring business after the country entered the reform and opening-up period in the late 1970s, with Can Xue dedicating most of her time to household matters and caring for their child.

It was in that time of reasonable prosperity and comparative leisure that Can Xue began writing. (Her nom de plume, perhaps fittingly, can be translated as “leftover snow.”) She entered the literary world at an important moment, when freedoms lost during the previous decade of political unrest were restored. Chinese contemporary literature flourished in the 1980s, and Can Xue, then in her 30s, was one of its brightest blossoms.

The first three decades of her life might not match those of the average Western author of her generation, but they are not peculiar when measured against her Chinese peers. Many of the writers who emerged in China after 1978 were raised by their grandparents as their intellectual parents ran afoul of radicals; many were kept out of higher education due to the suspension of college entrance exams between 1966 and 1976. And so, a generation of writers listened to village stories from their grandmothers or from the locals they met while sent down to the countryside, sifted through their parents’ volumes of modern masters like Lu Xun (鲁迅) and Shen Congwen (沈从文), and were then struck by the fever for Western modernism that swept the country in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

The combined influences of folk stories, classical literature, revolutionary symbolism, rural portraits, and modernism were near-universal, but it produced many different sorts of writers: there was Han Shaogong writing literary ethnographies of rural Hunan, Jia Pingwa telling contemporary stories within the framework of folk tale and the Ming vernacular novel, Wang Anyi refracting small-town life through Russian masters and Jiangnan fables. Can Xue’s unique experimentalism came from the same experience—thumbing through Lu Xun in her father’s dormitory, listening to the stories of the countryside, and then, belatedly, crashing into Franz Kafka.

Those influences were apparent in “Soap Bubbles in the Dirty Water,” the first story she published in 1985, which begins:

My mother has melted into a basin of soap bubbles. Nobody knows what happened. I would be called a beast, a contemptible, sinister murderer, if anyone knew.

She was channeling the spirit of Kafka, but also perhaps the strange stories told around countryside stoves. Many writers of that time were self-consciously freeing themselves from the shackles of realism, but “Soap Bubbles in the Dirty Water,” which appeared in New Creation, a low-circulation provincial literary journal, stands out now for the boldness of its experimentation.

Between 1985 and 1986, Can Xue published a handful more short stories and novellas, breaking out of the smaller-circulation journals and magazines enough times to catch the interest of literary tastemakers.

By the late 1980s, Can Xue started attracting the interest of translators and publishers from abroad. The French and Japanese got there first, as they did with other Chinese writers of her generation, followed by the English-speaking world. For better and worse, her readers became mostly foreigners: This might have held back her career within the literary bureaucracy and scotched her chances of producing firestorms of publicity, but it helped her build the global fame that she now enjoys.

The reasons for the global interest in Can Xue’s writing are obvious. Her writing was political, which thrilled the Sinologists still searching in the late 1980s and early 1990s for dissident writers to champion, but as she was writing about more universal torment, her writing appealed more widely.

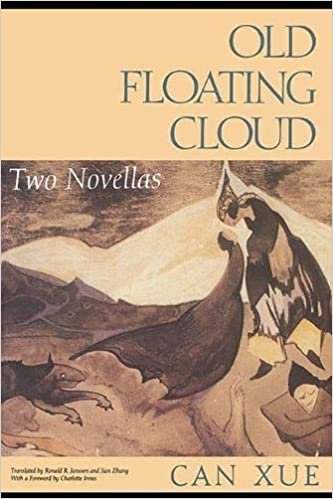

In her two early and widely translated novellas—Old Floating Cloud and Yellow Mud Street—she set herself apart by mastering a cozy experimental mode: these were difficult, strange books, but clearly written by a master of short fiction, rather than an academic shut-in. Yellow Mud Street, a disorienting, claustrophobic story about strange events in a rural township, works as a modernist novella, and invites philosophical pondering of the nature of reality, but deep down in its core, it is a freaky, timeless ghost story. At the center of Old Floating Cloud is a domestic tale that flirts enough with realism to comfort those not ready for formal experimentation or narrative games, but drags those willing to go further into a parallel reality of filth and decay. Interpreting Kafka and Jorge Luis Borges, she was writing in a style that felt familiar to a global audience, but there was also something in the spectral imagery and spooky stories that seemed essentially Chinese.

Even though she was more widely translated than many Chinese writers, it was still only a meager proportion of her output that made it into foreign languages. By the 2000s, while her reputation was solidified in her own country, she was in danger of fading away from global consciousness, becoming one of the many chronically under-translated giants of global letters (many Chinese writers belong in this category).

The turning point for Can Xue—and the beginning of Nobel chatter—came with the publication of several late-career masterpieces, their prompt translation into English, and renewed attention to her trove of short fiction. Between 2000 and 2020, translators went to work on Can Xue. Karen Gernant and Chen Ziping translated the short story collections Blue Light in the Sky & Other Stories and I Live in the Slums in 2006 and 2020, as well as the novels Five Spice Street and Frontier in 2009 and 2017. Annelise Finegan Wasmoen translated the novels The Last Lover and Love in the New Millennium in 2014 and 2018.

It was during this period that Susan Sontag declared that Can Xue deserved the Nobel. In 2016, she was longlisted for the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, and the Man Booker International Prize in 2019.

The first of Can Xue’s novels to be translated into English, Five Spice Street played a crucial role in building her reputation. A mind-bending experimental brick, loosely structured around small-town gossip about an adulterous relationship between a Madam X and a Mr. Q, it sealed her fortune in world literature. Translators Karen Gernant and Chen Ziping brought remarkable linguistic skill to the work, flawlessly capturing corner gossip, pompous officialese, and a stiff narration that reads in English as intentionally anachronistic—a self-conscious revival of a style found only in experimental fiction from a century ago.

Although details suggested a Chinese setting, the small town in Five Spice Street evoked the no-place of dystopian cinema, or an austere stage for a Bertolt Brecht play. Characters in the book refuse to take shape. Madam X, who the narrator places in the spotlight, is never truly known. Even though many have seen her, her physical appearance remains up for debate:

She is a middle-aged woman, very thin, with white teeth, a neck that’s either slender or flabby, skin that’s either smooth or rough, a voice that’s either melodious or wild, and a body that’s either sexy or devoid of sex. When this obscure image takes us by surprise and ‘‘discloses its true face,’’ everything unfathomable becomes clear, but only for an instant.

It is difficult to be sure what to make of the conclusion of the story, in which Madam X’s husband leaves her, her house collapses, and she is unwillingly elected the “people’s representative.” Possible philosophical or even political interpretations loom for moments before fading away, buried under further contradictions or negations. The American writer Brendan Patrick Hughes, in his glowing review of Five Spice Street, concludes that Can Xue was playing a marvelous trick on the reader. “On Five Spice Street,” he writes, “nothing means anything.”

In other words, it was the sort of writing that Can Xue had been fixated on perfecting since her name first appeared in print in 1985. “I view all of my works as a whole that is indivisible,” she said in an interview with the American novelist Porochista Khakpour in 2017, comparing her body of work to “a tree that is growing continuously all the time.”

What has changed, though, in the intervening years, is the literary landscape, which has shifted away from the surrealistic modernist games that Can Xue practices. Five Spice Street became a book unlike anything else available in English-language contemporary fiction—except for other novels and collections by Can Xue. She might not have won the Nobel this time around, but one gets the feeling that her popularity and acclaim will only continue to build.