Unequal or nonexistent laws left women in ancient China who faced abuse with very few options

Su Min’s journey to freedom began with a solo road trip in September 2020, an attempt to break free from decades of abuse and hardship that had silenced her for too long. As she traveled, this 56-year-old woman documented her experiences on social media, and her videos quickly went viral, inspiring countless women across China to stand up for themselves.

This September, her incredible story came to life on the big screen with Like A Rolling Stone, which earned over 80 million yuan at the box office in just 10 days and a stellar rating of 8.6 on Douban, China’s largest film review platform. But despite the overwhelming public support and legal assistance, Su’s attempts to divorce her abusive husband still took years, with her husband finally signing the divorce papers this July after she gave him 160,000 yuan of her hard-earned money.

In ancient China, women who fell victim to domestic abuse had even fewer options in a society that emphasized obedience and submission.

Throughout Chinese history, domestic violence has been treated differently from other violent crimes. Laws addressing domestic violence, when they existed, often distinguished between men and women, with husbands receiving lighter punishments for abusing their wives, even when the wives were royalty.

Read more about crime and punishment in ancient China:

- Yang Xiuqiong: How China’s First Female Olympian Paid the Price of Fame

- Ancient China's Most Famous Detectives

- Shadow Games: The Cunning Art of Espionage in Ancient China

During the Qin dynasty (221 – 206 BCE), there had been laws in place to protect women from domestic violence, stipulating that if a husband assaulted his wife and the injuries were significant—such as “tearing her ears” or causing broken limbs—his punishment would be having his beard and sideburns shaved, a penalty known as “耐 (nài).” This was the same punishment given for public brawls resulting in facial or bodily injuries. However, laws addressing domestic violence became less fair during the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), which stated that if a wife acted violently and her husband beat her without using weapons, he could avoid punishment even if she suffered injuries.

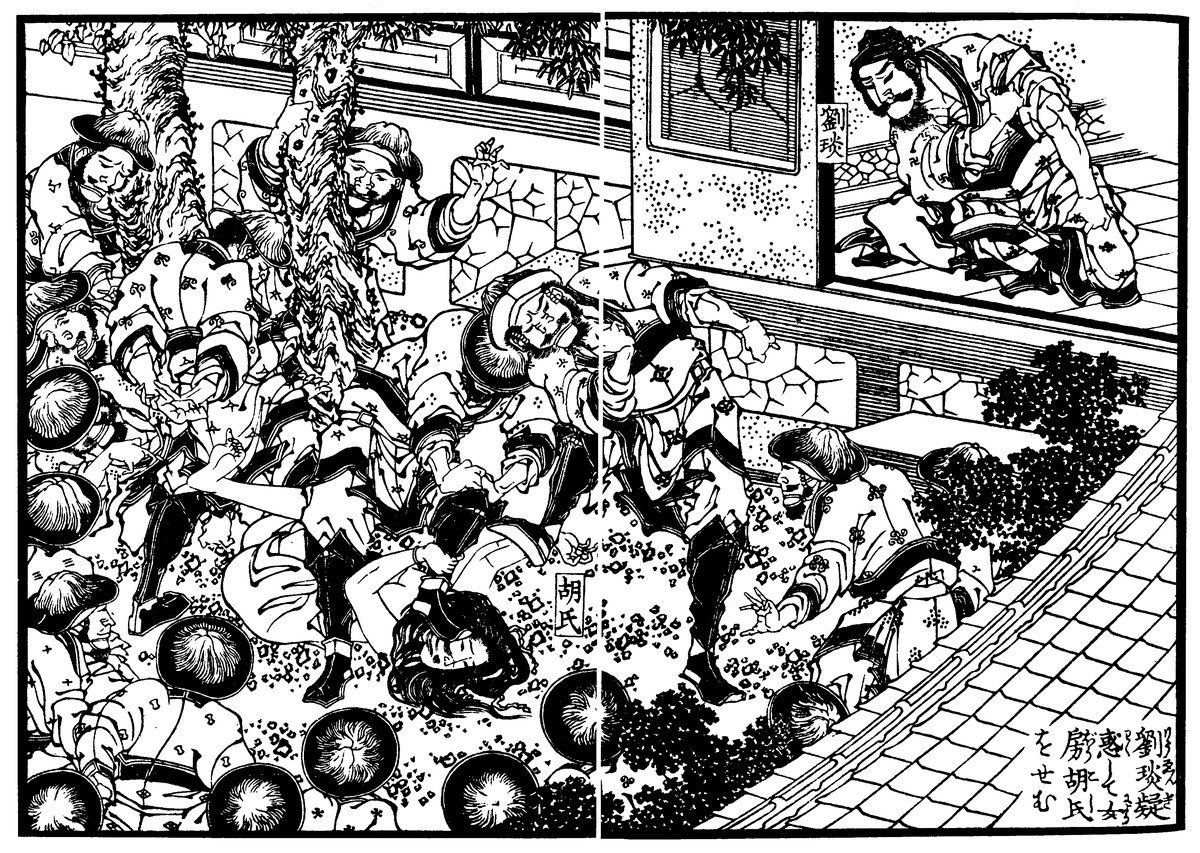

A slightly positive change occurred during the Three Kingdoms period (220 – 280). In the Shu Han kingdom, China saw its first recorded instance of capital punishment for domestic violence. According to the Records of the Three Kingdoms (《三国志》), in 234, the highly-ranked official Liu Yan’s (刘琰) wife, surnamed Hu, visited the palace to celebrate the New Year with the Empress Dowager. The Empress Dowager took a liking to Hu and invited her to stay for a month. Upon her return, Liu Yan, suspecting Hu had an affair with the emperor during her stay, ordered soldiers to beat her, striking her face with a shoe. He then divorced her and threw her out. Hu reported Liu Yan’s abuse to the authorities, leading to his arrest and eventual execution—although this may have been because Liu Yan’s actions offended imperial authority.

During the Southern and Northern dynasties (420 – 589), historical records show that husbands who beat or even killed their wives were treated leniently. In the 6th century, the pregnant Princess Lanling (兰陵公主) was shoved off her bed and brutally beaten after confronting her husband Liu Hui (刘辉) about his infidelity. Tragically, she soon died after miscarrying.

This incident sparked intense debate. The imperial family, represented by the Empress Dowager, condemned Liu Hui’s actions as murder and treason, demanding his execution for killing a royal. However, many officials argued that killing one’s own wife and unborn child was a private family matter and should not warrant the death penalty. According to the History of the Northern Wei (《魏书》), imperial pressure led to Liu Hui getting the death sentence, but he was later pardoned and even had his official title restored after several years.

Read more about badass ladies who challenged the rules:

- Badass Ladies of Chinese History: The Poet Li Qingzhao

- Tang Qunying: One of China’s Earliest Feminists

- For Land’s Sake: The Women Fighting to Keep Hold of Their Rural Land

The History of the Northern Wei documented another incident, where a 15-year-old boy named Zhangsun Lü (长孙虑) pleaded for leniency on behalf of his father, whose violent acts led to his mother’s death. Zhangsun’s mother had a fondness for drinking, and one time, his father, attempting to stop her, fatally beat her with a stick. After his father’s arrest, Zhangsun petitioned for clemency, arguing that the death was an accident and that without his father, his four younger brothers and younger sister would not survive. He even offered to take the punishment in his father’s place. Moved by his display of filial piety, the emperor pardoned Zhangsun’s father, sentencing him to exile instead. This story appears in the “Filial Piety” section of the History of the Northern Wei, reflecting the societal values of the time.

The penalties for violent acts between spouses became more clearly distinguished during the Tang dynasty (618 – 907). If a husband assaulted his wife and inflicted minor injuries, he would be punished “two degrees” less severely than if he had assaulted a non-relative. Conversely, if a wife assaulted her husband, she would be sentenced to one year of imprisonment; if the assault resulted in serious injury, the penalty would be three degrees more severe than for assaulting a non-relative. Only in cases where the assault resulted in death would the perpetrator face the death penalty, regardless of gender.

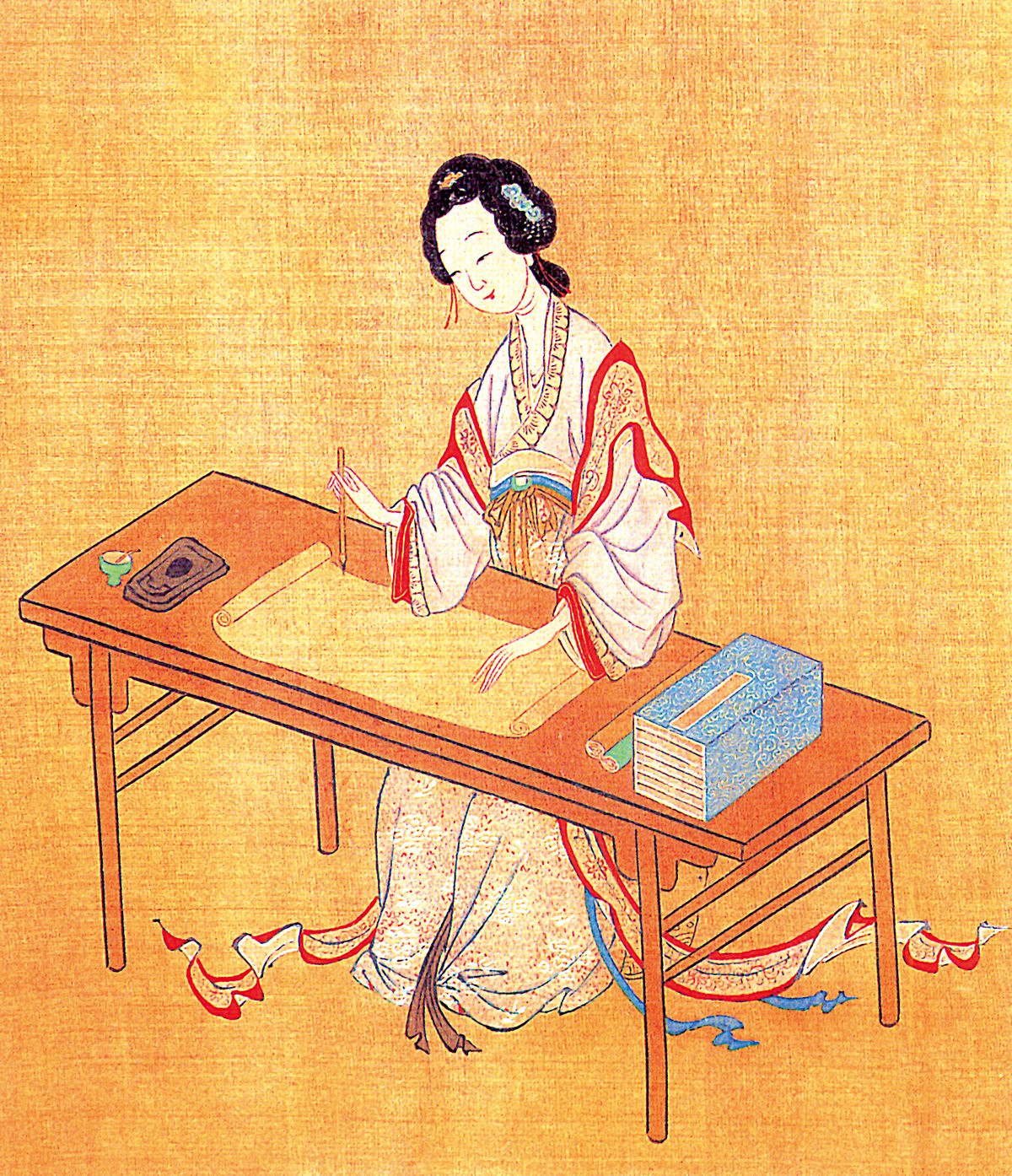

An added stipulation made things more dire for women in the Song dynasty (960 – 1279): “If a wife accuses her husband, even if the accusation is true, she shall still be sentenced to two years of imprisonment.” The renowned poet Li Qingzhao (李清照) falls victim to this oppressive legal framework. After the death of her first husband, Li fled south with a large collection of bronze and stone artifacts. During the trip, she met her second husband, Zhang Rushou (张汝舟). However, soon after they were married, Li discovered Zhang’s real object—to seize her valuable possessions. When she refused to hand over her possessions, Zhang verbally and physically abused her. Li reported Zhang to the authorities for domestic violence and corruption, and was granted a divorce after his crimes were verified. However, for accusing her husband, she was also imprisoned. With the help of some noble friends, she was released after nine days in jail.

During the Ming (1368 – 1644) and Qing (1616 – 1911) dynasties, laws regarding domestic violence grew increasingly unequal. If a husband assaulted his wife, he would face no consequences if there were no injuries; if the wife was injured, and she reported it, the husband would be punished two degrees less severely than for assaulting a stranger. Conversely, if a wife assaulted her husband, even without inflicting injury, she would receive 100 strokes of the cane; if the husband was injured, the penalty would be three degrees more severe than assaulting a stranger; if the husband became disabled as a result, the wife faced strangulation. Meanwhile, the husband would be sentenced to strangulation if he beat his spouse to death, but if the wife beat her husband to death, she would be beheaded or dismembered.

When it comes to domestic violence laws, it’s only in the modern epoch that a glimmer of hope emerges. China’s current constitution confirms the principle of gender equality, and for the handling of domestic violence, there is no longer a distinction between genders. The “Anti-Domestic Violence Law,” which took effect in 2016, provides further legal basis for combating domestic violence, offering more protection for victims.

But many victims, including Su Min, still find it difficult to collect evidence of abuse that is accepted by the court. Even the film, Like A Rolling Stone, left out the part about domestic abuse during the adaptation. Like many women in history before her, Su’s bravery and tenacity are impressive, but challenges undeniably remain for systematic change.